A report from Noah Arjomand, titled “The Folly of Double Government: Lessons from the First Anglo-Afghan War for the 21st Century” and published by the Afghan Analysts Network this month, outlines why the unique governmental structure maintained by the British during and after the First Anglo-Afghan war failed — and what that failure can tell us about modern Afghanistan.

The Great Game was a “veritable cold war between the British and Russian empires” in the 19th century. Imperial Russia pressed south, extending its influence through Central Asia. By the end of the century, one by one each of the great khanates (Kokand, Bukhara, and Khiva) would fall into Russian orbit. Even before the khanates fell, the British empire felt threatened — more specifically the British feared that Russia was setting its sights on the crown jewel: India.

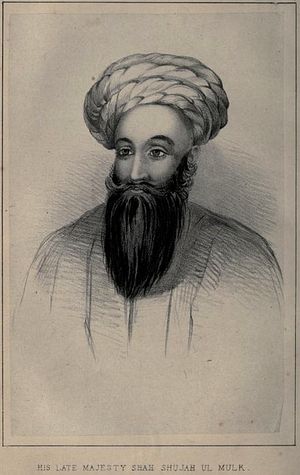

In 1839 the British began to suspect that Afghanistan, led by Amir Dost Muhammad Khan, was swinging toward the Russians. Dost Muhammad had rejected British pressure to subject his foreign policy to their will and renewed relations with Russia instead. In response, the British sent the East India Company’s Army to restore Shah Shuja al-Mulk (also known as Shuja Durrani) to the throne.

Arjomand writes that after putting “their man” back on the throne, the British “embarked upon an experiment in state-building designed — they insisted — to shore up popular support for Shah Shuja and set his governments on its feet.” Arjomand notes that the British genuinely viewed Afghanistan as a buffer state — they were concerned with its strategic location and not contemplating territorial acquisition. Establishing “Afghan independence,” however, was viewed as not just plucking Dost Muhammad from his throne and sidelining his tribal faction (the Barakzai) in favor of Shah Shuja and the Durranis, but encouraging the transformation of the Afghan state and economy.

While on paper the British aimed to “offer advice,” reality was decidedly different. Colonial systems, Arjomand explains, typically fell into two categories: direct and indirect rule. What the British set up in Afghanistan, however, he calls “double government” — “an uneasy mix of indirect and direct rule.” Arjomand continues:

Like indirect rule, it seeks to work through rulers who hold local legitimacy; however, double government also features a colonial administration working in parallel to the local ruler. The colonial administration directly intervenes in local politics with the aim of reshaping the state headed by that local ruler.

As Arjomand makes clear later, “Double government’s central contradiction in Afghanistan was that Shah Shuja was to be the sovereign king, but the British were present in Kabul to ensure that he acted as the right kind of king.”

Arjomand then dives into the specifics of how British government operated — from attempts at tax, military, and even prostitution reforms — and the tensions between colonial administrators, Shah Shuja, and the Afghan people. Shah Shuja was robbed of his ability to tell his subjects one thing and the British another. The British, as the AAN summary notes, oscillated “between non-intervention and state-building activism.”

The failure of British double government, Arjomand stresses, “should not be dismissed simply as an example of an attempt to impose centralization and bureaucratization on a country that has rejected it throughout history.” Indeed, after returning to the throne Dost Muhammad successfully created a national bureaucracy and a regular standing army. Dost Muhammad (and another subsequent leader, Amir Rahman Khan) “sacrificed subservience in foreign policy to the British for foreign support (without direct foreign intervention) that allowed them to consolidate power within Afghanistan.” It is not that Afghanistan is ungovernable, but that the system of double government is inefficient, contradictory, and sets the local ruler up for failure of one kind or another.

Interventions and adventures in state-building from the past two decades, such as those in Afghanistan, share characteristics with British double government: they are very expensive administratively and foreign actors often end up circumventing or overruling the very same government they aim to build up. Leaders — such as Hamid Karzai, and surely Ashraf Ghani now as well — face “the dual challenge of reassuring their foreign patrons of their commitment to ideals of good governance while also convincing their domestic constituents of their local authenticity and independence from those patrons.” Local rulers, so tightly observed, cannot say one thing to their people and a different thing to foreigners — either they become labeled a liar or seem to be a puppet.

So what can be learned? Arjomand is careful not to dismiss the reformist goals of such double governments, but he aims instead to simply point out that double government “does not create a state capable of effectively pursuing those goals.” In the end, comments which AAN highlights from an Indian who worked as a political assistant to the British during the First Anglo-Afghan war describe the contradiction, the frustrating clash, between good intentions and reality:

Inwardly or secretly we interfered in all transactions, contrary to the terms of our own engagement with the Shah; and outwardly we wore the mask of neutrality. In this manner we gave annoyance to the king upon the one hand, and disappointment to the people upon the other.

The report is available here.