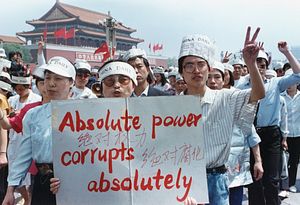

The gunshots on June 4, 1989 in China signaled the failure of the political reforms sought by the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party during the 1980s. This failure wasn’t accidental – it was a result of a complex competition between different factions within the CCP.

For China’s political reforms during the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping was the crucial factor. From the late 1970s, Deng gradually established his own power with the Party. While not possessing the absolute power of Mao Zedong, Deng’s power grew with the successful implementation of reform and opening up. But even then, there was a conservative faction that tried to reverse Deng’s reforms. Within the Party, there were two main political factions: the pro-reform camp was represented by Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang and the conservative camp led by Chen Yun, Li Xiannian, Li Peng, and Yao Yilin. And Deng himself, who championed reform and opening even while insisting on the “Four Cardinal Principles,” became the deciding voice between the two groups.

Most of the time, Deng’s reformist views were exactly opposed to the opinions of the conservative camp, but that didn’t prevent him from standing with the conservatives on the issue of how to handle the 1989 democracy protests. On the question of preserving one-party rule, their opinions were exactly aligned.

Zhao Ziyang, Deng Xiaoping, and the Conservatives

On the surface, Zhao, as the general secretary of the CCP’s Central Committee, had the power to lead reforms, but in actuality, his position vis-a-vis the top leadership was quite weak. That meant that Zhao had a hard time getting like-minded associates appointed to positions of power within the various Chinese bureaucracies. The Organization Department, which handles promotions and assignments for Party members, was led by Song Ping, a member of the conservative faction.

To push forward any major changes, Zhao would need the support of Deng Xiaoping first. In the early 1980s, Zhao and Deng had a strong rapport. With Deng’s support, Zhao’s economic reforms succeeded. After the 13th Party Congress in 1987, though Zhao was officially the general secretary, he would still need Deng’s support to enact the desired political reforms. Up until early 1989, Zhao had this backing.

From the 1970s through the 80s, from Sichuan to Beijing, Zhao relied on Deng’s trust and support – too much so, as it turned out. Zhao thought that he understood (and was understood by) Deng. Although he knew that there was a limit to Deng’s support, the events of 1989 showed that Zhao had miscalculated the extent of Deng’s trust and his own control over the Central Committee. In truth, Deng did not support Zhao personally, but rather supported him because he would firmly carry out Deng’s own vision for economic and political reform.

On the question of political reform, though, Deng and Zhao were not entirely in sync. Deng hoped to reform the existing system, making it more efficient without entirely overturning it. Zhao, meanwhile, who was the true leader of the political reform movement, sought to change the way the Party wielded power, with the end goal of establishing a democracy. Under the aegis of Deng’s vision, Zhao conducted a bold experiment — trying to transform China’s highly centralized political system into a modern constitutional democracy.

The differences in Deng and Zhao’s goals eventually led Deng to stop supporting Zhao and throw his weight in with the conservatives to kill political reform. In the early summer of 1989, Deng believed that Zhao was seeking to use the democracy protests to push for more political reform, endangering one-party rule in China.

In May 1989, when the situation threatened Deng’s bottom line, his support for Zhao evaporated. Deng suppressed the student movement and stopped the political reforms cold. When Zhao opposed martial law and the use of force to end the protests, he was deposed by Deng.

Even when he had Deng’s support, Zhao faced steep opposition from the conservatives. The conservative faction had already seen their hand strengthened at the 13th Party Congress in 1987, when two ultraconservatives (Li Peng and Yao Yilin) made it on the five-member Politburo Standing Committee. The conservatives now had the ability to interfere with and influence Zhao’s work.

More seriously, the conservatives knew that if they wanted to change the direction of China’s reforms, they needed to remove Zhao from power. Beginning in April 1989, Li and Yao used Deng’s fear of the democracy movement to accuse Zhao of “supporting chaos,” leading to the final decision to use force to suppress the movement. In the end, the conservatives used Deng’s strength to get rid of Zhao.

Zhao and the People

Zhao was aware of the danger. He knew that, in addition to defending against attacks from the conservatives, he needed to prevent his political reforms from affecting social stability. If the push for democratization went too far, it could become hard to control, which would give the conservative faction a way to attack or even halt political reforms.

Because of this, Zhao’s political reforms had to be relatively opaque. He couldn’t openly display these reforms before society, but that precaution cost him any hope of public understanding. As another consequence of this opacity, the many intellectuals in China, as well as the general public, didn’t see the fierce struggle going on between Zhao and other members of the Central Committee, nor did they see the many difficulties facing his reform agenda, again costing Zhao public support.

Immediately after the 13th Party Congress, the public was fairly content. But as time went on, Zhao’s political reform agenda faced heavy opposition. Meanwhile, price reforms were blocked, leading to high inflation. As the people weathered inflation, they grew upset with the corruption caused by a lack of restrictions on the use of political power as well as the lack of public oversight for officials.

From late 1988 to early 1989, democracy advocates in China became more and more vocal, putting pressure on Zhao from both conservatives (who wanted to oust Zhao) and society at large, where demands for democracy grew each day. Public calls for democratization were on one level helpful to Zhao’s political reform agenda, but at the same time, Zhao was the general secretary. Maintaining social stability was his responsibility.

Zhao and those working for him knew that social turbulence was a possibility, but looking back it’s apparent that they didn’t take the issue seriously enough. They did research on the possibility of social unrest, but not on what measures could be taken to deal with the issue. They also weren’t prepared for an ever fiercer intra-Party struggle and the way that would complicate social upheaval.

Zhao and those working for him made mistakes in pursuing political reform, and in how they handled the student protests of 1989. That’s only natural — they were men, not gods. Zhao in particular was well aware of the complexity and ferocity of the struggle for power within the Party, but after entering the top leadership he was not willing to use political machinations to harm his rivals, especially Party elders like Chen Yun and Deng Xiaoping. Instead he sought to win their support.

The fundamental reason the political reforms of the 1980s failed was that the reform forces within the Party didn’t have enough political power compared to their rivals. That’s beyond doubt. But Zhao’s own personal weakness also had an impact on political reforms, and the fate of the student movement. As Bao Tong [formerly Zhao’s policy secretary], once told me:

Ziyang was a richly experienced politician. As premier and general secretary, he handled things skillfully. But he had a personal weakness: he lacked the spirit to go on the offensive, to be bold and decisive in the midst of a sharp and complicated political struggle, and to courageously fight for the realization of his own political goals. This sort of weakness could be called being “honest and considerate” in an ordinary person, but for a politician, it can be fatal at the crucial moment.

Wu Wei, a former Chinese government official, is the author of On Stage and Backstage: China’s Political Reform in the 1980s.