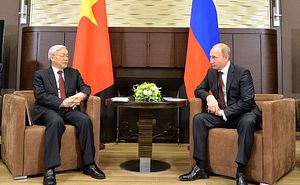

Last week, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam Nguyen Phu Trong completed a five-day visit to the United States, meeting U.S. President Barack Obama, a move widely considered a landmark in what is becoming one of the most intriguing bilateral relationships in the Asia-Pacific.

Unlike Xi Jinping, the Vietnamese leader does not hold any official position within the government, which formally makes him a representative of nothing more than a political party, though it is clear that he is among the few who effectively run the country. Given the CPV’s monopoly on power, accepting this difference in the political structures of the two states is a significant gesture by the White House, one that demonstrates a willingness to go beyond ideology in the interest-driven environment of contemporary world politics.

When speaking about burgeoning U.S.-Vietnam relations, China is always the elephant in the room. The dynamism of bilateral ties is to a great extent determined by Beijing’s mode of operation in the Asia-Pacific. Both Hanoi and Washington can reiterate statements about their ties being a good in themselves, and indeed they probably are, but one can’t ignore Vietnam’s central role in U.S. regional strategy aimed at accommodating and managing China’s growing influence. In a similar fashion, relations with the U.S. are crucial for Vietnamese foreign policy as a hedge against excessive dependence on China.

While China is never missed in any U.S.-Vietnam relations analysis, Russia is often omitted (to the disappointment of Asia-watchers in Russia). This isn’t exactly fair, because as Hanoi and Washington may be moving to an “extensive” and “comprehensive” partnership, it is still not “strategic” – a characteristic that has special importance attached to it by diplomats in Russia and, more importantly, Vietnam. Given the current tension in U.S.-Russia relations, what is Moscow’s position in this complex Asian game?

“Traditional” is another popular adjective in contemporary Vietnam-Russia rhetoric. It has little to do with the pragmatic foreign policy pursued by the Vietnamese leadership, so perhaps it would be more useful to think about Russia’s place in Hanoi’s priority list in simpler terms. What is it that Russia can do for Vietnam that the U.S. cannot?

The first thing that comes to mind is arms trade. Russia has been a supplier of military equipment to Vietnam since the war and continues to be the main source of the country’s naval modernization. At the core of this relationship is the six Kilo-class submarine contract complemented by Klub surface-to-surface missiles. Though lifting the embargo will enable the U.S. to sell (or give) the Vietnamese military equipment for the Coast Guard and Navy – and we can see this happening already – it is clear that it would take Vietnam decades to readjust completely to new hardware. So Russia is likely to remain the key arms trade partner amid tensions in the South China Sea, which are unlikely to be resolved in the observable future.

Russia has another very significant advantage over the U.S. as Vietnam’s counterpart for political dialogue. In the eyes of the Communist Party of Vietnam cooperation with Russia is not accompanied by any kind of “hostile” ideology export. There is no fear that Moscow will be pushing for reforms the Party cannot afford at this point in time and Russia will not be setting any conditions for military equipment trade, investment, or humanitarian cooperation. And this is precisely the kind of concerns the elites in Vietnam have about their romance with the United States.

What Russia can’t afford in its relations with Vietnam is as important a question. Ties with the West severely damaged by the Ukraine crisis, China has got all the attention as the centerpiece of Moscow’s new Asia-Pacific rebalance. There is thus almost no way Russia would risk its rediscovered partnership with China by supporting Vietnam’s approach to the South China Sea issue (not to mention the territorial claims themselves). On the other hand, the Obama administration has made it rather clear that it would pay great attention to any state that has issues with the Chinese march for regional leadership. To put it bluntly: Vietnam’s quarrels with China are one of the drivers of its partnership with the U.S. and one of the irritants in its partnership with Russia.

But it is not just Beijing’s invisible hand holding back the Russia-Vietnam relations. The economic downturn in Russia means it can’t match the U.S. as a buyer of Vietnamese goods. The Eurasian Economic Union-Vietnam Free Trade Area (FTA) set to take effect in 2016 may foster bilateral trade, but the country’s share of Vietnamese exports will most likely remain below 2 percent. The purchasing power and the structure of economic relations is just too different from that of the U.S.

Where does that leave us? The U.S.-Vietnam rapprochement, as impressive as it may be, is certainly not a marriage, but more of an affair. Going too far in this affair and causing too much trouble to China may entail a disaster for a small state like Vietnam. Diversification is key to becoming a middle power and Russia’s potential for being the “third force” is immense. If the U.S. administration really wants a strong, independent, and stable Vietnam, it should respect its long-term ties with Russia.

With all the U.S. limitations on military cooperation, it is essentially Russia that is doing most of the work building Vietnamese maritime capacity and imposing the costs for China. It would be very unwise to create linkage between U.S.-Russia tensions in Europe and let them spill out into Asia.

Anton Tsvetov is the Media and Government Relations Manager at the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), a Moscow-based foreign policy think tank. He tweets on Asian affairs and Russian foreign policy at @antsvetov and blogs for Russia Beyond the Headlines (Asia). The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of RIAC.