Afghan President Ashraf Ghani seems to have arrived at the same conclusion about Pakistan that his predecessor did but after making a sincere 10-month effort to reach out to his meddlesome neighbor. The realization, therefore, is that much starker.

After a series of bloody attacks on the Afghan army, police and U.S. special forces in Kabul over the weekend that killed more than 57 people, Ghani accused Pakistan of sending “messages of war” and sheltering suicide bombers, supplying them with military-grade explosives and doing nothing to halt their plans.

Within hours of his angry statements, the U.S. State Department came to Pakistan’s rescue, saying Washington did not have “specific intelligence” to conclude whether Islamabad was involved in the attacks. Privately, officials conveyed a sense that Ghani was “posturing” since he had gone out on a political limb to make peace with Pakistan and was disappointed.

The attacks followed revelations that Mullah Omar had died in 2013 in Karachi, a fact that was kept hidden both by the Taliban and its mentors, the Pakistani army and the ISI. The Pakistan-sponsored “peace talks” collapsed as a bitter struggle ensued to claim Omar’s mantle.

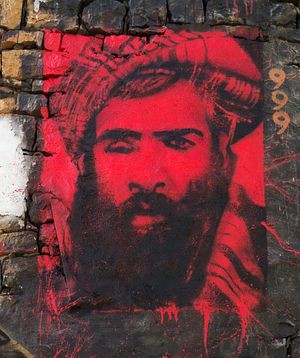

Pakistan’s man is Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansur, who had been acting in Mullah Omar’s name, with ISI’s help. He is believed to have endorsed peace talks with Afghanistan but Mansur’s first act to prove his leadership was to let loose a dance of death against the Afghan people and security forces.

In Pakistani and American reckoning, Ghani is supposed to “understand” and absorb the attacks in the context of various Taliban factions vying for control. An editorial in Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper justified the violence with these remarkable words: “The wave of Taliban attacks may be partly for the new leadership, or the leadership contenders, to establish their bona fides as genuine Taliban leaders and not mere power-hungry leaders.”

So twisted has Pakistan’s logic become that even respectable newspapers casually suggest that only violence justifies “genuine” leadership.

The end result – to quote former Indian Ambassador to Afghanistan Jayant Prasad – is that the “Pakistan-led, Pakistan-owned” peace process has collapsed like a “house of cards.” Pakistan’s ability to “deliver” the Taliban is in question.

The unfortunate part is that the United States seems to have played along in keeping Omar’s death under wraps. U.S. press reports indicate that Washington had its suspicions but didn’t push the Pakistanis for proof. The reasons why are not clear.

U.S. officials deny they knew of Omar’s death and believe that Pakistan didn’t know either. It was not a “giant ruse” in the words of one official. But the calculation appears to have been in favor of keeping the appearance of a unified enemy as opposed to exposing the lie.

The developments of the last two weeks raise important questions about how U.S. policy in the region is unfolding. There is no question that Washington will stay engaged – and it should – with both Pakistan and Afghanistan but “how” is what concerns Pakistan’s two immediate neighbors – Afghanistan and India.

Do these developments warrant a re-think and tweaking of U.S. policy in the region? So far Washington seems to give all the rope needed to Pakistan’s army-ISI combine to figure it out while it defends Islamabad in public and private. But the space for rationalizing Pakistan’s behavior is shrinking.

The sense among U.S. officials remains that Pakistan is trying hard and is frustrated with the Taliban. They believe the Pakistanis can’t and don’t effectively control the Taliban leadership. They reject Indian and Afghan arguments that the ISI does indeed exercise control by providing lines of communication, weapons, access, shelter and a window to the outside world.

Even if Pakistan’s control is not positive but “negative” – through threats to kill family members or other coercion – Pakistani minders give enough evidence of being more influential than Washington believes.

U.S. officials say Pakistan wants a “relatively stable” government in Afghanistan but one that is not overly sympathetic to India. But by endorsing this veto on how the Afghans fashion their future, the Americans also become complicit in the mess.

At the same time U.S. officials also insist they no longer see Pakistan with the old rose-tinted glasses and don’t necessarily buy the argument that it has made a “strategic shift” in favor of peaceful co-existence or that it’s ready to shed its terrorist tool box.

But if Pakistan hasn’t made a strategic shift then why give its deceptive arguments so much weight? The only logical explanation can be that the U.S. government agrees with and accepts that the government in Kabul should accommodate Islamabad’s insecurities by keeping India at a distance.

In the end, this is not a good remedy and we all know it.

Seema Sirohi is a Washington-based analyst and a frequent contributor to Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Seema is also on Twitter, and her handle is @seemasirohi. This article was originally published at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, a foreign policy think tank in Mumbai, India, established to engage India’s leading corporations and individuals in debate and scholarship on India’s foreign policy and the nation’s role in global affairs.