In one of his famous essays Sir Francis Bacon says “some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested: that is, some books are to be read only in parts, others to be read, but not curiously, and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.”

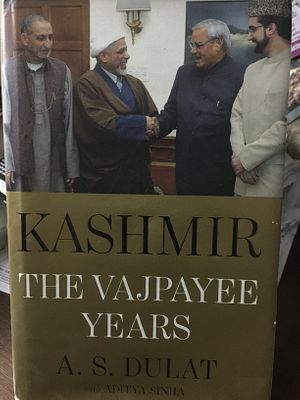

Amarjit Singh Dulat’s book, Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years has to be “tasted.” It narrates the story of contemporary Kashmir. It outlines the history of the last twenty five years of the Kashmir valley.

Dulat is a former special director of the Intelligence Bureau and a former chief of India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the country’s external spy agency. When in the 1980s the valley started burning, Dulat was posted there and witnessed the state’s descent into chaos. He was also in charge of Kashmir while working in the Indian prime minister’s office between 1998 to 2004, when the government was led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

Therefore, what we have in the book is an insider’s perspective of the time when the Himalayan state was undergoing a particularly difficult phase in its perennially difficult history–cross-border terrorism, the killing of Kashmiri pandits and the valley’s Hindu population, and the Kargil War between India and Pakistan all took place during this time.

The book, co-authored with Aditya Sinha, discusses India’s engagement with Kashmir at a different level. It outlines how the Indian state engages different players–politicians, insurgents, and militants–in its search for an ever-elusive peace. The different layers of engagement reveal not only the coercive nature of the state, but also the government’s cunning in playing one actor against the others. First, there are those who want a merger with Pakistan. Second, there are those who favor independence. Finally, there are those who want to be part of India. The spy chief inadvertently exposes the duplicitous game played by India by not allowing the local political players to shape the region’s future. The deep engagement and interference of the Indian establishment ultimately prevents stabilization.

The book also exposes how separatists are used by both India and Pakistan to serve their interests.

Dulat notes that the Vajpayee era, between 1998 to 2004, was the most fruitful and productive time in Kashmir. It was a time when the foundation for future peace was laid down. Vajpayee visited Pakistan twice and, despite the war in Kargil in 1999, he agreed to engage Islamabad when Musharraf came to Agra to hold talks with Indian leaders in 2001. The attack on the Indian parliament in 2001 by Pakistan-based militants again broke the momentum for peace, but both nations came back to the negotiating table again when Vajpayee visited Islamabad in early 2004.

However, Dulat says that the defeat of the first Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in 2004 at the hands of Congress cost Kashmir lasting peace. According to him, Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf, at the time, suggested an out-of-the-box solutions to the Kashmir imbroglio. He had a four point formula: “making borders irrelevant by allowing the free movement of Kashmiris across the LoC (Line of Control), self governance, which meant autonomy but not independence; demilitarization;

Dulat believes that had the formula been implemented, it could have led to the formalization of the LoC as the official border between India and Pakistan in Kashmir, negation of demands for a plebiscite in the valley, and an end at last to the unfinished business of partition. This could have heralded a new era of peace in the subcontinent. But Dulat rues that the defeat of Vajpayee in 2004 and a lack of enthusiasm by his successor, Manmohan Singh, killed the initiative in its infancy.

But Dulat fails to answer why the BJP government under Narendra Modi has not yet tried to revive this old venture with Pakistan. Kashmir holds the key to stability in South Asia. The book lays great emphasis on talks with Pakistan. Make no mistake: the narrative in Dulat’s book is one-sided and has been written from the perspective of New Delhi. As a result, we don’t get to hear Pakistan’s side of the story. Dulat’s account also fails to highlight the highhandedness of Indian security forces in the valley. As the country’s supreme spy chief, Dulat does not try to tell the story of the hundreds of missing youth in the valley since the 1980s. He does not touch upon the intrusive nature of the Indian military in the valley. The book remains silent on the basic question of why a sizable section of Kashmir’s population remains alienated from the mainstream.

Is India holding Kashmir together or is Kashmir, in effect, holding India together? The book does not answer this question. The latest literature on Kashmir scratches only the top layer of the Kashmir problem and fails to go deep and provide true insight into the problem at hand. Readers picking up this book should, thus, heed Sir Francis Bacon’s sage advice and avoid reading “curiously.”