The Rebalance authors Mercy Kuo and Angie Tang regularly engage subject-matter experts, policy practitioners and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into the U.S. rebalance to Asia. This conversation with Professor Rosemary Foot – Emeritus Fellow of St. Antony’s College and Senior Research Fellow at Oxford University’s Department of Politics and International Relations and Research Associate at Oxford’s China Centre with recent publications including The Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia and China, the United States and Global Order – is the fifteenth in “The Rebalance Insight Series.”

Professor Foot, over the past 40 years you have analyzed the evolution of U.S.-China relations. What key factors will determine the future direction of this strategic relationship?

Some 40 or so years ago, an anti-Soviet strategic alignment underpinned the Sino-American relationship. However, from the 1980s onwards the relationship became multidimensional in form. The two states have well-developed economic ties, the inter-societal bonds are quite strong, and they regard each other as major strategic rivals and occasionally even as collaborators in certain foreign policy areas. We have to accept that there are both competitive and cooperative elements in the relationship, now and into the future. But if the economic and social bonds remain mutually beneficial and the strategic rivalry is managed then we will continue to witness the evolution of a relationship that continues to be complex and difficult, but not wholly adversarial.

Domestic politics on both sides are also crucially important to the future direction of relations. The U.S. rebalance to Asia has given the Asia dimension of U.S. policy greater coherence and prominence. The next administration may choose to maintain that policy (probably the case if Hillary Clinton becomes the next U.S. President) or may seek to alter some of its fundamentals and overall to toughen the stance towards China, as many of the Republican candidates seem to suggest is possible. On the China side, President Xi Jinping leads an elite decision-making group that combines both an internationalist outlook with strong nationalist sentiment. Were the Chinese leadership to tip further in the nationalist direction and become more internally focused – perhaps as a result of serious domestic unrest connected with a major economic slowdown – then levels of China-U.S. hostility are likely to increase. If the Chinese government remains outward looking and focused on development via an integrationist model, then there will be greater stability in Sino-American ties.

What are underlying assumptions in Chinese strategies vis-à-vis U.S. global leadership in a multipolar world?

The Chinese message with respect to U.S. global leadership has been rather inconsistent, which perhaps reflects the fact that there is a range of views among China’s political elites. Some view the U.S. as in inexorable, relative, decline and that U.S. influence globally will inevitably diminish to China’s overall benefit. Others among the elite are more wary. They appear to see the United States as still powerful, but perhaps more intent on spreading the burdens of leadership rather than the advantages that the sharing of leadership might bring. For this group, the U.S. strategy is a subtle form of containment of China, since if Beijing is induced to respond to a U.S. global agenda, this could lead to the country becoming overstretched.

How would you assess the U.S. rebalance to Asia, and how might the next White House – Democrat or Republican – bolster U.S. leadership in Asia?

A generous interpretation of the U.S. rebalance would see it as a subtle, multidimensional strategy that combines all three areas of policy: military, diplomatic and economic. It is meant to reassure U.S. allies and other Asia-Pacific states at a time of strategic uncertainty that the United States has committed to maintaining the security and prosperity of the region. At the same time, the U.S. has also been trying to convey the message that it does not wish to be the instigator of a polarizing rivalry with China. Thus, a further dimension of the rebalance has been to emphasize that the U.S. seeks to build on coincidences of interest with China and expand areas of cooperation. This is a difficult policy to enact, but its successful fulfillment is probably one we should all wish for.

The next U.S. administration can help to bolster U.S. leadership in Asia by thinking seriously about the factors that have led America to be welcomed in the region as a “benign hegemon.” Among other things, that means contributions to regional public goods and eschewal of policies that are conceived narrowly and solely in terms of a U.S. national interest.

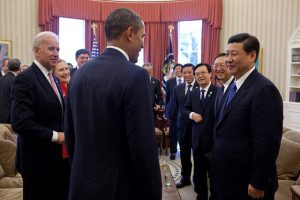

At the 2013 Sunnylands summit, President Xi Jinping called for a “new model of major power relations,” which the White House quickly eschewed. With Xi’s state visit to the United States in September, what core message should Washington and Beijing convey to each other, their domestic audiences and the international community?

My preferences for the September state visit include a desire to see statements that indicate both sides appreciate this is a complex bilateral relationship that requires and will be given constant attention. I would also hope to see signature of agreements that point to a serious intent to manage the strategic rivalry. For example, fleshed out agreements to help both sides avoid incidents at sea and in the air, and a detailed explanation of the two sides’ positions on freedom of navigation and on how best to guarantee that freedom.

What three leadership characteristics are essential for the next U.S. president to optimize U.S.-China relations?

The next U.S. president needs to combine consistency of purpose with consistency of message. Valuable too would be an ability to see the world through the eyes of ordinary Chinese and their leaders. This latter point is not meant to imply that the United States doesn’t have its own legitimate goals and purposes that it will want to pursue, but empathy is an important attribute of leadership. It helps a leader avoid double standards and appreciate the strategic dilemmas that other governments face.