Former South Korean president and dictator Park Chung-hee’s legacy casts a long shadow over the country’s modern history. A former lieutenant in the Japanese Kwantung Army, Park witnessed firsthand the state-directed developmental program implemented in the puppet state of Manchukuo (modern day northeast China). This, as Hironori Sasada speculates, was instrumental in teaching Park how a developmental state might be constructed — in South Korea. Indeed, between 1962 and his death in 1979, Park would go on to do just that, along with other developmental dictators like Chiang Kai-shek and Lee Kuan Yew.

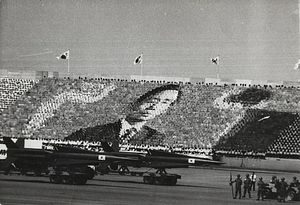

Park, as dictators go, was anything but benevolent. Developmental states, overbearing by nature, severely oppress — often ruthlessly — civil society. The Yushin System, implemented in 1972 and lasting until Chun Doo-hwan’s military coup, effectively granted Park full dictatorial powers through the dissolution of the National Assembly and the suspension of the Constitution. (Park had governed semi-democratically before then.) The slew of emergency decrees that followed permitted a severe crackdown on society: protesters, activists, and dissidents were often jailed and tortured; many died in captivity or during confrontations with riot police or the military.

Given the repressive and sometimes violent nature of Park’s developmental regime, one might reasonably think that Park’s legacy is largely a negative one. Indeed, as Chalmers Johnson, a pioneer of developmental state literature, once wrote, “Had Park, in the early 1970s, retired to Taegu and assumed the role of senior statesman supervising his carefully chosen successors… he would be hailed today as the greatest Korean Leader of modern times — and would probably still be alive.”

While Park’s legacy remains divisive, he is being remembered in an increasingly positive light. Or so recent polling data would suggest.

In a recent Joongang Ilbo article, Seoul National University professor Kang Won-taek writes that Park Chung-hee is positively evaluated in the areas of political and economic development. The 2015 polling data show that, in the political realm, 74.3 percent positively assess Park. Regarding economic growth, an overwhelming 93.3 percent give the thumbs up.

Roh Moo-hyun, the author indicates, is the only president who can compete with Park’s positive ratings. In the political realm, 70.8 percent positively assess Roh, and the economic 59.7 percent.

Unfortunately, Kang does not provide a breakdown of the poll, or even the source of his data. This will give methodologists and close readers cause for concern — it may perhaps lead some, especially those who are made uncomfortable by the numbers, to simply disregard the article altogether. But corroborating numbers exist.

For the 70th anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, Gallup Korea conducted a poll of 2,003 people over six days in July and August, asking them “which president did the best job leading the country after liberation.” Of all respondents, 44 percent said Park Chung-hee. As one might predict after reading Kang’s piece, Roh Moo-hyun came in second (24 percent) followed by Kim Dae-jung (14 percent), Syngman Rhee (3 percent), Chun Doo-hwan (3 percent), Kim Young-sam (1 percent), Lee Myung-bak (1 percent), and Roh Tae-woo (0.1 percent).

Furthermore, 67 percent of respondents said Park “did many good things” (for comparison, 54 percent said Roh “did many good things”). And among those good things done, 52 percent listed “economic development,” 15 percent said the “New Village Movement,” and 12 percent said “improving the lives of the people.” Notably, among the “wrong things done,” 74 percent said the Yushin Dictatorship; 10 percent said the military coup d’etat.

What do these numbers mean? While polling data can only say so much, it indicates the power of South Korea’s rags-to-riches story. It says little to nothing of the sufferings endured by ordinary South Koreans at the hands of the state, but it goes to show just how important status and prestige are to people. As recent work on South Korean nationalism show, young Koreans are very status-conscious and, one might say, “proud” of Korea’s economic development. Even if people learn about the “era of emergency decrees,” Cheon Tae-il, and the political oppression of the 1970s and 1980s, it won’t necessarily stop them from holding somewhat contradictory opinions: Yushin was bad, but Park, well, he was all right. Look at us now.