With Chinese leader Xi Jinping in the U.K. for a four day visit, we have another chance to observe one of the most striking ways he differentiates himself from his predecessors. A simple look at the list of countries he has visited as they are set out on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs website shows in just 31 months since assuming the role of president, he has clocked up trips to 33 nations.

Even more remarkable is the diversity of these destinations. There are, of course, the standard places one would expect – four visits to Russia, two to the United States, three to Indonesia. Most of these visits were to attend international fora like the Bandung Conference, the Shanghai Co-operation Organization summit, or the Sochi Winter Olympics. But then there are an array of bilateral visits made for purely diplomatic reasons – a trip to South Africa in 2013, just after the first foreign visit he made as country leader (to Moscow); almost all the Central Asian states in the autumn of 2013; a large swathe of central Europe the following spring, with Latin America later that year, and then South Asia in September, and Australia and New Zealand at the end of the year. In 2014 alone, Xi managed to clock up visits to no less than 20 countries.

Can we discern any patterns from this diplomatic hyper-activity? Firstly, in view of his frequent flying habits, the two most obvious omissions on this list – Japan and North Korea – become even more conspicuous. And while the strains with Japan since 2010 are well understood, and make the failure to pay a visit there comprehensible, the omission of North Korea is truly an anomaly. It speaks volumes that Xi has been able to visit places like Fiji (population 881,000), Maldives (345,000), and Trinidad and Tobago (1.3 million), which barely figure on most leaders’ radar, while he so far hasn’t found the time to sit on a plane for an hour in order to pay a visit to one of his country’s supposedly closest diplomatic allies. Even the perfect pretext offered by the recent 70th anniversary of the Korean Workers Party in North Korea failed to entice him to go. The lack of a single destination in the Middle East so far, despite the region being China’s largest source of imported petrol, is also striking.

Secondly, Xi’s travels tell us something about the strategic priorities of the current Beijing leadership. That the most important current leader in their system is taking such effort to travel extensively to other countries and undertake grueling visits shows that this must be deemed worthwhile. So despite hints to the contrary — the real awareness of the range and depth of internal challenges that China is facing in the era of falling GDP growth, all the complaints about how pushy it has become in its region, and how hard it is for international non-governmental bodies and companies to do things in the country — maintaining extensive and productive relations with the outside world is still seen as a core priority by its topmost leader and worth significant amounts of his very limited and precious time.

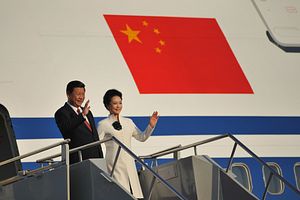

Of course, this might all be explained easily enough from the domestic propaganda benefits it brings. The images of Xi being garnered in praise and glory by foreigners are beamed back into China from across the world, serving as at least one means of gaining deeper domestic legitimacy and support. In this way Xi’s travels play a part in the strategic game plan of this leadership – they are positioning themselves as in charge of a party that has the best chance of making China a pivotal, powerful player in the world. The photo ops from Xi’s trips provide evidence of the ways China’s new influence is receiving validation and recognition beyond the country’s borders.

Seen in this light, it is odd that the outside world does not leverage this hunger for images of Chinese leaders having good relations with foreigners more. Academic M. Taylor Fravel, in Strong Country, Secure Borders (Columbia 2008), noted patterns in the way that when China made significant deals over its many outstanding border disputes, often in the favor of other countries, when the leadership felt vulnerable and unstable domestically. By 2010, China had resolved nearly all of these disputes. Fravel found that in the early 1960s in particular, at a time of great domestic challenges, the country was willing to cut deals in order to give its international environment some predictability while it fought to stabilize its own internal issues. We might be seeing a similar process now. Xi’s travel activism deploys a huge amount of very important time, political attention, and capital. It is clearly done for a reason. Xi didn’t just go to Fiji, Maldives, New Zealand and Costa Rica — which have a combined population of less than ten million — to pass the time.

If Xi’s travels are a sign of just how internally challenged Chinese leaders now feel their country is, then the outside world does have a tangible way to gauge its continuing importance to Beijing, for all China’s shrill, self-confident exterior in recent years. This gives other countries an opportunity to think hard about what sort of price they want in return for all these images Xi is getting for his propagandists back home. The world matters to the Chinese leaders far more than has been suspected up till now, for foreign countries offer one of the few things beyond energy resources that Beijing continues to need from the world beyond its borders – flattery and admiration. Unlike with commodity and energy prices, however, the value of these things has only continued to rise in Beijing.