As Japan recovers from recent torrential flooding, concerns about nuclear safety are never far from people’s minds. During the flooding, bags of contaminated debris were swept away from cleanup sites associated with the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Japan also restarted commercial operation of domestic nuclear generation last month under more rigorous, post-accident rules. Amidst these developments, questions linger over whether the country should (or even is ready to) expand its nuclear operations. For this, answers may lie in fuller public engagement.

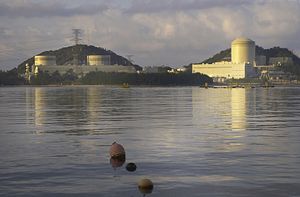

In August, news broadcasts showed the control room of Japan’s Sendai No. 1 Reactor renewing initial operations. Among those protesting the restart was former Prime Minister Naoto Kan, who held office during the Fukushima accident. Shortly after the reactor’s restart, five cracked tubes were discovered in the reactor’s cooling system, requiring new mitigation measures.

To put the experience into broader context, Japan is highly seismic and volcanic in nature. It is home to 110 active volcanoes and has 1,500 earthquakes of varying magnitudes each year. In August, the Japanese Meteorological Agency warned of larger-than-usual risks (prompting evacuation) in conjunction with volcanic eruptions at Mt. Sakurajima. Based roughly 30 miles from the restarted Sendai plant, the volcano is one of the most active in Japan, with volcanic sediment from previous flow found three miles from the plant.

Critics of Japan’s nuclear restart point out that new safety rules and evacuation planning are not adequate. Sufficient numbers of buses, for example, are not available in some areas should the need for evacuation arise. It is also not entirely clear whether design adaptations to Japan’s nuclear fleet adequately account for international best practices and the country’s natural conditions. Moreover, polls indicate strong misgivings by a majority of Japanese people who favor a slow phase-out of nuclear technology.

By contrast, supporters see promise in Japan’s return to nuclear generation. As an island nation with few natural resources, nuclear energy offers a form of low carbon, power generation that can run nearly continuously. This past summer, Japan experienced one of its hottest seasons in recent history with utility usage rates running at 80-95 percent, as 43 operable nuclear plants remained idle. Kyushu Electric, the utility which manages the Sendai plant, reportedly paid more than double its costs following the accident for alternative generation. With the restart at the Sendai plant, economic benefits are projected to equal $25 million per year for the local economy. (This compares with estimates of accident-related damages valuing the abandoned region, homes, businesses, and agricultural land alone at $250-500 billion in a national economy of $4.7 trillion.)

Looking ahead, Japan’s current, national energy plan outlines a goal of meeting 20 percent of domestic energy supply with nuclear generation by 2030. The country’s new nuclear regulator and safety infrastructure will also undergo a review in January 2016 with the International Atomic Energy Agency. Yet, some say economic recovery has dominated political decision-making at the expense of more difficult discussions about risk in the country’s energy choices.

At this juncture, Japan has the chance to create a more durable national energy strategy. To begin, public discussions should present tradeoffs and risks in technically viable energy options. Meetings should openly convey information about the assumptions and challenges in reasonably understandable form, and include top policymakers, safety regulators, members of industry and citizens. Discussions should also allow for consideration of alternative options, like renewable energy and changes in practices, with rationale for costs and benefits. These exchanges could provide greater visibility to what may be a new safety culture, while also enabling better cross-sectoral channels for widespread learning. A national referendum could then follow, asking which national energy path Japanese citizens will support and on what terms (for instance, higher taxes or costs passed to consumers). This approach would require more time and broad-based commitment, but prioritizing safety and fuller societal buy-in may prove to be more sustaining for Japan over the longer term.

For a country that has witnessed some of the darkest moments in nuclear history and also shown unmistakable evidence of resilience and innovation, Japan now has a unique opportunity to chart a more enduring path with policy and safety implications that can resonate globally. If nuclear energy is to have a chance at being sustainable in Japan, public officials, the nuclear industry, and the country’s citizens will need to openly engage about what is known and assumed in their complex set of energy choices.

Kathleen Araújo is an assistant professor at Stony Brook University, specializing in national decision-making on energy-environmental systems, and science and technology policy.