What a difference six years makes. In Copenhagen, it was the Asian giants, most notably China, who were blamed for the failure of COP15, which derailed global action against climate change for several years, during which greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions continued to rise and extreme weather events became more and more frequent.

Last week, in stark contrast, all countries wanted action on climate change, and though deciding how to do this was a challenge, in the end we got an agreement that was, though far from perfect, more robust than many had anticipated in the run-up to COP21.

“In Paris, there were no heroes or villains – all countries moved from their positions in the end,” said Lou Leonard, vice president of climate change at the World Wildlife Federation.

It included a mention of human rights in the preamble, a strong ambition mechanism, a collective stocktake of emissions reduction actions in 2018, followed by a regular, ratchet-up mechanism to ensure that the Internally Determined National Contributions (INDCs) each nation submitted prior to COP21 are scaled up over time. It also established that support for capacity building in developing countries – crucial for much of Asia – would launch in 2016, and enshrined transparency, a key demand of many developing countries.

What changed? Quite simply, Asia. The past few years has seen the environment emerge as a serious issue across the region. In China, it is air pollution that is forcing the government to take action, while in the Philippines, it was Typhoon Haiyan two years ago that really made it clear what the highly vulnerable archipelago nation would have to deal with if climate change continued unabated. Moreover, in 2009, for most Asian countries, cutting emissions sounded like a sure-fire way to slash future growth potential. Why cut emissions for a problem that was primarily caused by the United States and Europe? But now, with solar expanding rapidly in India, and China leading the world in renewables, peaking emissions in the coming years no longer sounds like a burden, but an opportunity.

“In India…the private sector can take advantage and move towards a prosperous low carbon future by demanding as well as investing in clean energy,” said Krishnan Pallassana, India executive director for The Climate Group. “The benefits for business are threefold: greater energy security, affordable supplies, and recognized leadership internationally.”

So in Paris, China entered as a country pushing for change – having submitted a strong INDC with a goal of peaking GHG emissions by 2030. India was feared by many as being this year’s China. At times it seemed schizophrenic. One day, it announced an ambitious, trillion-dollar International Solar Alliance, and then, days later, stood alongside fossil-fuel dependent Saudi Arabia in refusing to accept a 1.5 degree warming limit. In the end, though, India was less of a roadblock than expected, though it still makes any future emissions reductions dependent on robust finance and technology transfer.

Conversely, another large Asian developing nation, the Philippines took on a leadership role at COP, as the chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, a grouping of 43 countries that pushed, successfully, for the inclusion of a 1.5 degree goal rather than a 2 degree one. They also were forceful in the inclusion of Loss & Damage, a mechanism to assist countries unable to prepare for climate change, in the final agreement. The CVF allowed the voices of developing nations – particularly the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) of the Pacific Ocean – to be far louder and more prominent in Paris than at any previous COP.

“These negotiations have made enormous progress, not only because of the ice breaking leadership of the U.S. and China, but also and perhaps ultimately more important participation and engagement of developing country parties,” said Gary Yohe, professor of economics and environmental studies at Wesleyan University.

What Now?

The deal is not perfect by any means, and one crucial weakness is the fact that emissions from shipping and aviation were not included in the deal. Singapore, which relies on trade for its economy and has one of the continent’s major shipping and aviation ports, was the main roadblock on this. Moreover, there was little mention of land-use emissions, the same year that we saw Indonesia’s unprecedented fires, which emit massive carbon dioxide. It is likely that these will be a topic at a future COP and will require compromise – and leadership – from Asia.

“The Paris Agreement did not reflect all we asked for…but Paris was never meant to be the last step,” said Krishneil Narayan, coordinator for the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network in a statement. “It was meant to be a progressive step in identifying new common grounds to address climate change together collectively through a new, universal agreement.”

Scientists themselves are concerned that the agreement does not do enough in the short term. They fear that, without drastic cuts now, we may emit enough GHG to get to 1.5 degrees in just the next five years.

“If we are truly committed to 1.5 degrees, then we have to shut off the light on the Monday after COP to meet this goal,” said Dr. Johan Rockström, executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, at COP21.

In other words, what came out of Paris is ultimately little more than a piece of paper that must now be acted upon, and fast. The mechanisms and operationalization of the agreement now fall to the United Nations, which much figure out how to disperse funds from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and develop a fair system for carbon accounting. But emissions reductions actions are the responsibility of the nearly 200 member-states, meaning the ultimate success of the agreement depends on Asia, responsible for the biggest proportion of global emissions.

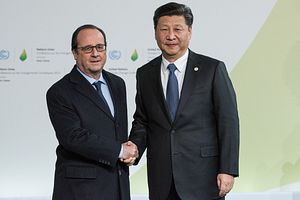

Another crucial factor will be the robustness of the climate finance mechanism, to be funded primarily by developed countries including Japan, and if technology transfer allows for the rapid expansion of clean energy as is hoped. Though French President Francois Hollande made it a center point of his post-agreement speech that the $100 billion figure for the GCF was a floor, in the final agreement, the date for the fund’s inception was pushed back by five years to 2025.

“Developed countries have obtained another five years to deliver what they agreed to do. It is regrettable that this has happened as it delays action in developing countries who are in need,” said Meena Raman, Legal Advisor at the Third World Network.

Nevertheless, when the agreement was announced, there were cries of joys, and even tears, at the Le Bourget conference center in Paris, along with a sense that this was historic. Twenty-one years after the Rio Earth Summit, more than three decades after scientists first pinned global warming on carbon dioxide emissions, and despite intense lobbying efforts by fossil fuel companies, we finally have an agreement.

Now the hard part begins. If this is truly Asia’s century, then Asia has the opportunity to make it a green one.

Nithin Coca is a freelance writer and journalist who focuses on cultural, economic, and environmental issues in developing countries. Follow him on Twitter @excinit.