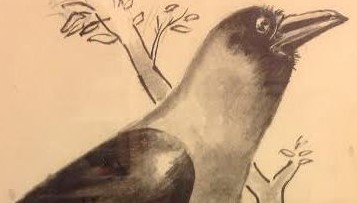

When R. K. Laxman passed away on January 26 last year, the people of India bade goodbye to the man who reigned over the world of Indian cartooning. Easily recognized by his “common man” character, Laxman’s graceful black and white editorial cartoons helped digest the news of the day. His oeuvre includes doodles and sketches from travels abroad and in India. He was particularly fond of sketching and painting the crow. His attention to drawing and detail bode well for his career and popularity: “You may see all these things around you every day, but it is up to the artist to make you notice them.”

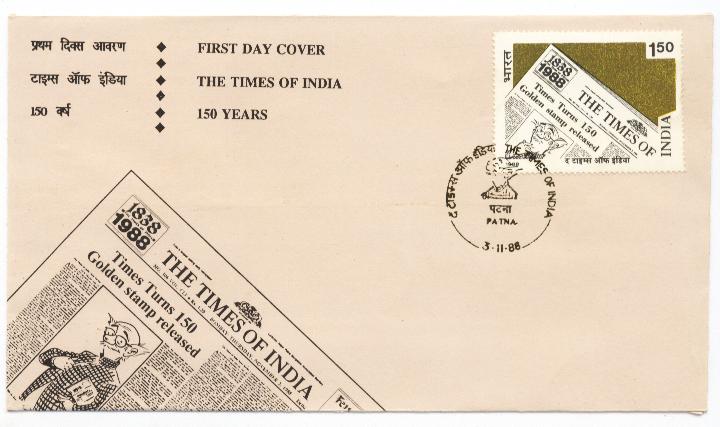

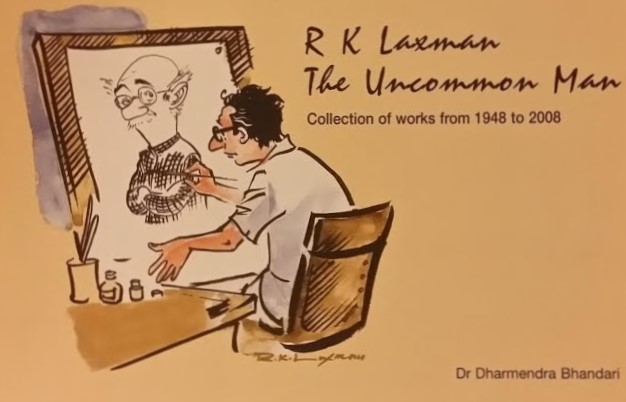

His inspiration for meticulous drawing came from the British cartoonist David Low. Temple carvings from the past also made him marvel at India’s fine artistry. Laxman’s acclaim led to an exhibition in the 1960s—the first cartoonist to be hosted in an art gallery. This is no small matter. For cartoons to enter the sacred precincts of an art gallery implied staking a claim as artist. The staff cartoonist of the Times of India, R. K. Laxman exemplified the cartoonist as artist as political analyst.

Laxman’s distinguished career is the story of the making of a cartoonist of national stature. For many junior cartoonists I met during my research on India’s cartooning culture, copying Laxman’s style was a pathway to success in the profession. Laxman was aware he had many imitators. “Editors find my example for the newcomers, although it is not the right thing to say. Each one must develop their own style,” reflected Laxman when I asked him how he felt about his work as a model for new cartoonists.

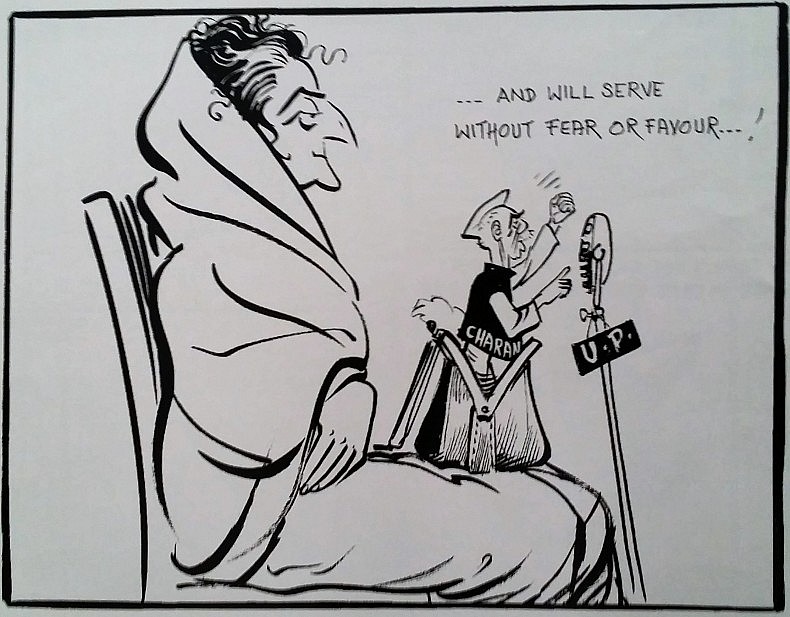

Laxman’s big cartoons appeared on the Times of India’s front page. “The puppet.” 1970. Courtesy: Dharmendra Bhandari.

India’s rich history of cartooning culture, beginning in its colonial years, includes a long list of cartoonists, many of whom have faded from public memory. Modeled after the British humor magazine, Punch or the London Charivari, the array of 19th century-vernacular Punch versions, came from all over colonial India. The Anglo-Gujarati Parsi Punch from Ahmedabad, the Urdu language Oudh Punch from Lucknow, and the Hindi language Hindu Punch from Calcutta, were among many titles that formed the “comic papers” landscape. These weekly newspapers brought cartoons and politics home. A study of these cartoons thwarts any attempt to demarcate the political and the social. This seamless flow of politics—at home and outside—was also the hallmark of Laxman’s large editorial cartoons and one-column pocket cartoon series, “You said it.”

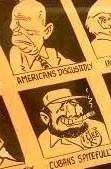

Laxman’s big editorial cartoons showed readers the world of Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and Rajiv Gandhi—the political dynasty he caricatured with precision. A witness to Indira Gandhi’s political career, Laxman gave her a long nose and chin. His poignant cartoon on her assassination in 1984, captured the betrayal of her security guards. Laxman’s palette sized up leaders from every part of the globe. The world of caricature makes the imagination soar. With Laxman readers saw Gandhi reading a newspaper in heaven exclaiming, “My. My! Whats happening to my country!” In his cartoons the Gods too received their earthly updates from the newspaper.

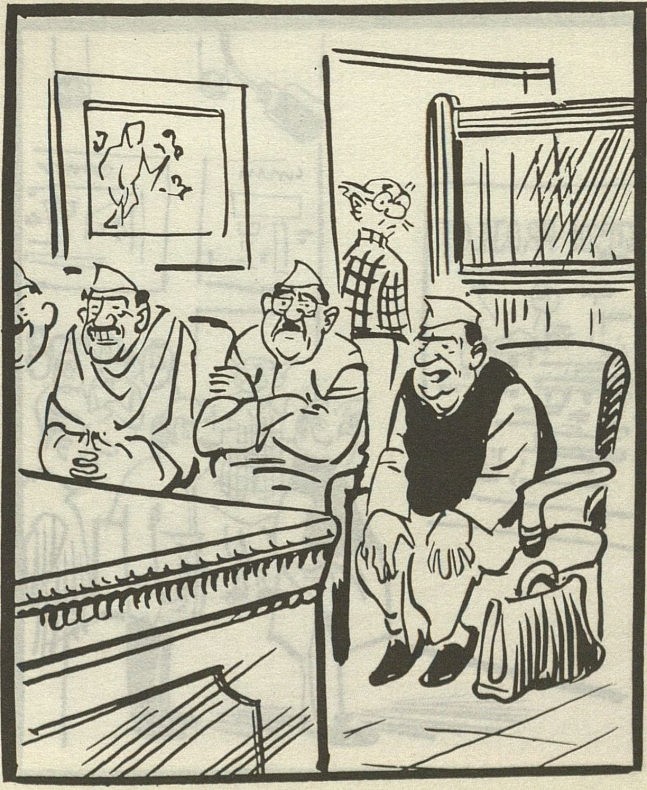

Laxman’s pocket cartoon world took the reader to the common man’s home, to the bureaucrat’s office, to the politician’s office, to a laboratory and to the street. As a “freewheeling commentary on socioeconomic, sociopolitical aspects in a rather lighter vein” the pocket cartoon was “meant to expose the general mood of the country.” The common man had no barriers. He’d hold files, take notes, or just linger among the retinue of bureaucrats. Here, every day, the common man overheard and witnessed politics. Laxman’s cartoons were well-suited to the Indian public’s untrammeled zest for politics: “As a nation we are rather prone to talk politics—whether at a bus-stand or in a railway compartment or in office.”

“Why should you, Sir? Corruption, cover-up, lying, misrule, bungling etc., can’t be sufficient reason for resigning.” Courtesy: R. K. Laxman

The common man did not speak and there was a reason for this. For Laxman, speech was a distraction and loss of power: “Silence is more powerful than eloquence. Actually silent people are more powerful.” But what was this power? Was this the power to endure without complaint? The reader was left to wonder. Contrary to this quiet demeanor, which was futile before politicians, bureaucrats and experts, his wife, the common woman, was outspoken. One should not be too quick to assume her speech signaled power. It didn’t. The common woman’s powerlessness—marked by her speech, equipped her to hiss at politicians and ridicule pernicious sycophants.

Although not a constant companion of her man, her arena of appearances included tea time with the political heavyweight Jayalalitha. The common woman’s commanding presence overshadowed her husband. In comparison, Jayalalitha looked like a big hot air balloon. The common couple’s bliss was incomplete without politics. This play of witnessing and voicing—sight and sound, and how it projected the presence and absence of power is unique to Laxman. He subverted expectations. Everyone spoke. The common man heard them all.

There is much debate about the identity of the common man. Was it Laxman? Or perhaps a regular citizen of India? Laxman was the most-interviewed cartoonist in India. In these interviews, one gets an intimate view of Laxman. Laxman’s sardonic humor was doled out in equal measure to all politicians. His quips in these interviews reminded me of the common woman. Not the common man.

Fond of travel, his writings and autobiography leave us with a wealth of knowledge about his visit to the House of Commons and meetings with David Low and Bertrand Russell, among other luminaries. He visited the United States on a Fulbright appointment. Laxman had appreciative words for British and European cartoonists and the American cartoonist, Herblock.

Laxman’s cartoons infuriated and touched hearts, revealing mighty politicians as vulnerable creatures. He regaled in cutting politicians down-to-size. Several interviews have noted his unequivocal disdain for politicians. Former Prime Minister Morarji Desai’s reacted to one of his cartoons by calling a formal meeting: “I did a cartoon criticizing his plans to ban horse-racing and crosswords. He felt outraged at my comment and called a full-dress Cabinet meeting to discuss how to eliminate the menace of the cartoonist.”

Laxman’s cartoons could also tear up a seasoned politician. In 2001, Member of Parliament Karan Singh, was moved to write a letter to the editor on Laxman’s cartoon on the earthquake in Gujarat: The cartoon “depicting a beggar contributing his proverbial one penny’s worth to the Gujarat Relief Fund was really a masterpiece. For a change, instead of a laugh, it brought tears to my eyes.”

Politicians are notorious for basking in the glory of their cartoons and caricatures. Laxman’s cartoons made politicians front-page news. But in Delhi, India’s political capital, Laxman’s admirers included a special person—the popular statesman and nuclear physicist, President Abdul P. J. Kalam. A people’s president, he presented Laxman’s cartoons as an antidote for hard lives and hard times. Such times made laughter and thought difficult: “Life even for the Common Man becomes worth living with Shri Laxman’s wit and wisdom in full cry. To laugh and make others laugh and to think and make others think is the unique gift of every cartoonist of repute. Shri Laxman excels himself in this.” Kalam’s autobiography, Wings of Fire, included a caricature by Laxman—a testimony of mutual admiration.

During the hugely popular Anna Hazare-led anti-corruption movement in 2011, Laxman’s common man sculpture was garlanded in a show of solidarity. For more than half a century Laxman thrived off the ambiguities of a democracy. Ironically, he became a mascot, of sorts, for credentialing India’s democracy. Indians and political parties of all hues have united in celebrating his cartoons. Postage stamps, national honors and honorary doctorates—Laxman conquered all.

Laxman’s common man statue at the Symbiosis Institute, Pune. He was garlanded during the Anna Hazare movement. Photograph by the author.

The only censorship Laxman suffered was in the Emergency years (1975-1977) when the Indian government muzzled all criticism of the state. But his cartoons have been caught in the crossfire of hurt sentiments. Readers’ complained that historical gender and caste-based inequities, unacceptable in a democratic nation, seeped into Laxman’s cartoons. These complaints of offence, as I note in my book, open a space for debating liberal politics and claiming rights. In a six-decade career, Laxman’s “offences” are a drop in the ocean.

Elsewhere I noted that the use of the cartoon is a public responsibility and a measure of public intelligence. It also falls on the cartoonist’s shoulders to be doubly attentive to the history of social discrimination and cultural stereotypes. The temptation to banish all barriers in the name of political humor and free speech, can pose an unexpected dilemma for cartoonists. They may find themselves hoisting privilege, power, and prejudice to the detriment of marginalized communities vigilant about violence in all forms. For many, protesting cartoons can be the most viable form of political intervention. Though, not all such protests emerge from the same ideological position.

One year since the Charlie Hebdo violence, and with French President Francois Hollande as India’s guest of honor at the Republic Day celebrations this year, one can ponder if the French can turn to Laxman’s cartoons. Knowing about cartooning cultures elsewhere opens one’s eyes and mind to cultural relativism. This lightens the burden of free speech and mends broken hearts. By turning to Laxman, one can take an overdue step: acknowledge the conspiracy of laughter.

The 2016 Republic Day celebrations this week in Delhi saw many firsts: a contingent of army canines, a French army contingent, and an all-women stunt contingent. A gift of Laxman’s cartoon books to Francois Hollande that day, which also was Laxman’s first death anniversary, would have been salutary. Laughter is also social glue.

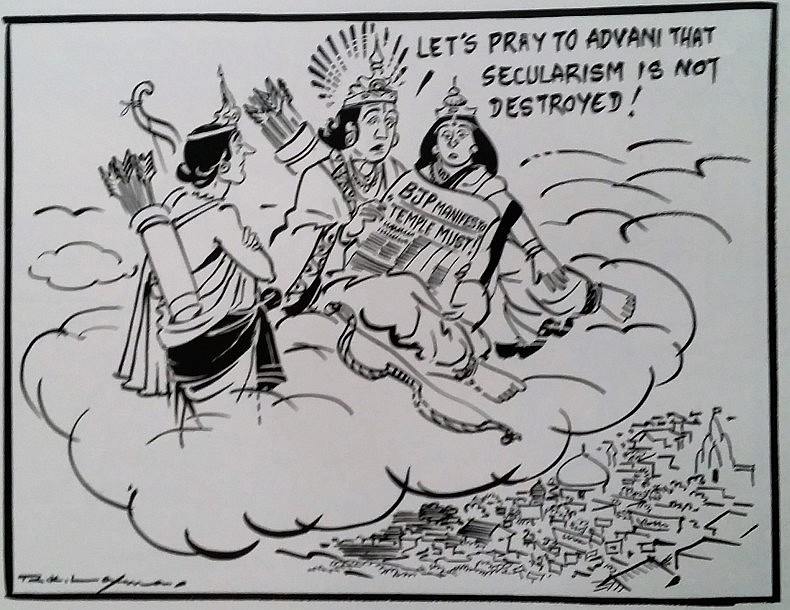

Laxman’s readers know that he caricatured the Hindu Gods. Many have seen his Ganesh caricatures. In one of his cartoons, depicting the deities Ram, Sita, and Laxman, he reversed the power hierarchy. In a bid to protect secularism, Lord Ram contemplated making a prayer to the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party stalwart, L. K. Advani. How provocative of Laxman to caricature secularism—the pillar of liberalism, as a divine intervention!

Laxman could take such liberties with his Gods—winning public adulation and the prestigious Magsaysay award. Indeed, the Gods are powerful.

So was Laxman.

Ritu Gairola Khanduri is a historian and cultural anthropologist. She is an associate professor at the University of Texas-Arlington.Ritu is the author of Caricaturing culture in India: cartoons and history in the modern world. Cambridge University Press. 2014. The paperback edition will be released in February 2016.