On February 22, 1946, a relatively unknown diplomat from the U.S. embassy in Moscow wrote a lengthy telegram analyzing the motivations of Soviet/Russian foreign policy and recommending a general policy approach that came to be known as “containment.” That diplomat, George F. Kennan, was subsequently appointed by Secretary of State George Marshall to head-up the newly created Policy Planning Staff at the State Department. Kennan and his staff were charged with taking a long-term view of American foreign policy based on current trends in international relations in the context of fundamental American geopolitical interests.

In the Long Telegram, Kennan combined penetrating insight into the motives of Soviet leaders, an analysis of the cultural and historical forces that influenced Soviet conduct, and realistic policy recommendations for meeting the Soviet challenge. A year later, Kennan, using the pseudonym “X,” wrote an article in Foreign Affairs entitled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” which popularized many of the ideas and policy recommendations of the Long Telegram. This ignited an important policy debate within the United States over the best way to respond to Soviet/Russian aggressive moves around the world. The influential columnist Walter Lippmann, for example, wrote a series of articles that criticized Kennan’s proposed policy for over-committing the United States to the defense of peripheral interests. Meanwhile, the political philosopher James Burnham wrote three books that criticized containment as insufficient and too defensive, and advocated a more offensive policy of “liberation.”

The Truman administration codified containment in a series of National Security Directives, including most famously NSC-68, and responded accordingly to Soviet moves in Berlin and the Eastern Mediterranean, and North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. The unpopular Korean War stalemate and the “loss” of China to the communists brought renewed criticism of containment, and the 1952 Eisenhower presidential campaign, led by the soon-to-be Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, called for replacing containment with a policy of “rolling-back” the Soviet empire. Eisenhower and his successors, however, hewed generally to the policy of containment throughout the Cold War, which is a testament to the practical realism and farsightedness of Kennan’s policy analysis.

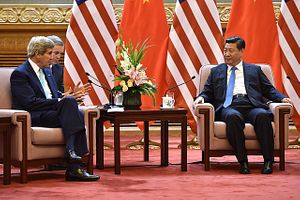

Seventy years later, the United States faces geopolitical challenges from China in the South China Sea, East China Sea, Central Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific region, and from Russia again in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. The United States has responded to these challenges with talk of a pivot or rebalance to Asia, improved diplomatic relations with Southeast Asian nations threatened by China, and general condemnation of Russia’s moves in Ukraine and Syria, but as yet there has been no long-term policy analysis and recommendations to rival Kennan’s Long Telegram.

It is time for some unknown diplomat in Beijing or obscure policymaker in the State Department or National Security Council to replicate George Kennan’s Long Telegram to provide insight and long-term guidance to American leaders faced with the contemporary Sino-Russian challenges. Since China poses the greater challenge, the new George Kennan should have extensive knowledge of Chinese history and culture, the nature of the Chinese political system, a political-historical-cultural knowledge of the entire Indo-Pacific region, and an appreciation for America’s fundamental geopolitical interests in commanding the seas and oceans and ensuring the political pluralism of the Eurasian landmass.

The United States needs an intellectual policy debate similar to the one spurred by Kennan’s analysis in the Long Telegram and “X” article. China’s rise, Europe’s decline, Russia’s revival, the proliferation of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, the spread of Islamic radicalism, and the relative shift in power from Europe to Asia present a challenge to what Walter Russell Mead has called the Anglo-American maritime world order that has broadly organized the global geopolitical environment since the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

That “order” may be ending no matter what general policy the United States adopts, but if so America needs to explore its role in the changing world order. It could do worse than to reflect on the wisdom, profundity, and erudition of George Kennan’s Long Telegram, which counseled U.S. leaders to “apprehend and recognize the nature” of the challenges, study them with “courage, detachment and objectivity,” and “educate the public” about geopolitical realities. “It is not enough,” he wrote, “to urge [countries] to develop political processes similar to our own,” rather it is necessary to “formulate and put forward for other nations a much more positive and constructive picture of [the] sort of world we would like to see” and “have [the] courage and self-confidence to cling to our own methods and conceptions of human society.”

Francis P. Sempa is the author of Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century (Transaction Books) and America’s Global Role: Essays and Reviews on National Security, Geopolitics and War (University Press of America). He is also a contributor to Population Decline and the Remaking of Great Power Politics (Potomac Books). He has written on historical and foreign policy topics for Joint Force Quarterly, American Diplomacy, the University Bookman, The Claremont Review of Books, The Diplomat, Strategic Review, the Washington Times and other publications. He is an attorney, an adjunct professor of political science at Wilkes University, and a contributing editor to American Diplomacy.