First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out –

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out –

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out –

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me.

Pastor Martin Niemöller’s words on German intellectuals who didn’t raise their voice against Nazis are pertinent for Indian intelligentsia when it comes to the issue of ethnic cleansing and persecution of minority Hindu community of Kashmir, known as Kashmiri Pandits. There has not been enough clamor for bringing to justice the perpetrators of the 1990 mass exodus of Pandits from Kashmir.

The mass exodus

Kashmir is a seat of intellect and knowledge with a recorded history of 5,000 years. It forms part of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), which is the only Indian state with a Muslim majority population and Hindus in the minority. Pakistan also claims the state, which it views as unfinished business leftover from India’s partition (even though the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India on October 26, 1947 when its ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, signed the Instrument of Accession with the Union of India).

In 1989-1990, thousands of Kashmiri Muslims, backed by Pakistan, rose against the Indian state with the aim of seceding J&K from the Union of India. The idea was to create an Islamic state of Jammu and Kashmir; a valley homogenous in its religious (read: Islamic) character.

The Hindu Pandits of Kashmir became the first target of the insurgency. They were viewed as living symbols, representing India in Kashmir. In order to spread fear among the Pandit community and oust them from Kashmir, the militants started targeting prominent Kashmiri Pandits in 1989. The first killing happened on September 14, 1989 when Tika Lal Taploo, a lawyer and the vice-president of the J&K state unit of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was shot dead in Srinagar.

On the night of January 19, 1990, Kashmir resonated with anti-India and anti-Pandit slogans: “Oh merciless, oh infidels, leave our Kashmir”; “If you want to stay in Kashmir, you have to say Allahu Akbar”; “We want Pakistan, along with Pandit women but not their men.” Mosques became planning centers for terrorist activities in Kashmir. Violent clashes between local protestors seeking freedom from India and security forces became the norm. The law and order situation in Kashmir collapsed; kidnappings, killings, and rapes became routine.

Terrorist organizations like the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) and Hizb-ul Mujahideen issued open threats to Kashmiri Pandits. They were given three choices – convert to Islam, leave Kashmir, or perish. Left with no choice, the minority Kashmiri Pandits fled the valley, leaving behind their homes to save themselves from persecution. Half a million Pandits were displaced, marking the largest-ever exodus of people since India’s partition in 1947. By the end of 1990, all of Kashmir was almost cleansed of Pandits.

The prolonged exile

After being forced from their homes, Kashmiri Pandits sought refuge in different parts of India, especially Jammu and Delhi. The aura of horror was such that most of the Pandit families left without any of their belongings. They left with the hope that the situation in Kashmir would return to normal soon, allowing them to go back to their homes. But the situation deteriorated day by day, and the chance to go back to their homeland never came.

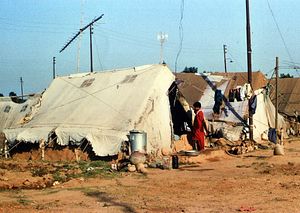

Some Pandits managed to get rented accommodations while many lived in squalid camps in Jammu. The state administration failed to provide dignified shelter to Pandit refugees. In the initial years of exile, in the early 1990s, thousands of Pandits succumbed to unaccustomed weather, sunstrokes, snake bites, and other ailments. The trauma of losing their home slowly and silently affected Kashmiri Pandits, particularly the elderly.

Thousands of Pandit families lived in these camps for almost two decades. Only in 2011 and 2012 were the Pandits living in the camps relocated to two-room tenements in Jagti, a town in Jammu province. Bit by bit, many Pandits have tried to rebuild their lives in Jammu and other parts of India, as their home in Kashmir has been lost.

Although most Pandit families left Kashmir in 1990, a few hundred families stayed. The horror of persecution always loomed over these Pandits. In 1997, 1998 and 2003, three major massacres happened in Sangrampora, Wandhama, and Nadimarg in which seven, 23, and 24 Kashmiri Pandits, respectively, were brutally killed. These massacres signaled to other Pandits not to return to their homeland.

The continued injustice

Kashmir passed through turbulent times in the 1990s. Terrorism was at its peak then, but gradually it was controlled by Indian security forces. After the lifting of Governor’s Rule in 1996, the National Conference came to power, headed by Dr. Farooq Abdullah. Along with the democratic election process, the preparation of roadmaps for a peaceful Jammu and Kashmir commenced. With those plans came assurances that Kashmiri Pandits would be brought back to their homes. Those promises remain unfulfilled.

Around 700 Pandits have been killed in the valley due to terrorism. Neither the Indian government nor the J&K state government has tried to address the issue of the ethnic cleansing and the persecution of Kashmiri Pandits. To date, there has been no judicial inquiry and no prosecution. There has not been any hue and cry over the killings of Pandits or the rapes of Pandit women in Kashmir.

The BJP has always claimed to be committed to the cause of justice for Kashmiri Pandits, including their return to their homes. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his election rallies and otherwise, has spoken about the issue of Kashmiri Pandits; the Pandits were also mentioned in the BJP’s poll manifesto. However, no concrete steps have been taken by the Modi-led government. The government keeps talking about the return of Kashmiri Pandits without addressing the fundamental issue of ethnic cleansing. A safe environment in Kashmir is indispensable for the return of Pandits. That will necessitate punishing the culprits responsible for the exodus.

The year 2015 was the 25th anniversary of the exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits from Kashmir. Today, January 19, a new year of exile begins. Will the Modi government find a solution to the issue, which has dragged on for a quarter of a century, or will the government behave like its predecessors?

Varad Sharma is the co-editor of A Long Dream of Home: The Persecution, Exodus and Exile of Kashmiri Pandits (published by Bloomsbury India). You can follow him on twitter at @VaradSharma.