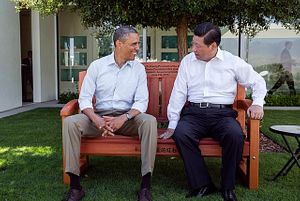

The “artificial earthquake” in North Korea caused by its fourth nuclear test has set off geopolitical tremors in U.S.-China relations, exposing the underlying gap between the two countries that has long been papered over by their common rhetorical commitment to Korean denuclearization. At their Sunnylands summit in June of 2013, Presidents Xi Jinping and Barack Obama vowed to work together on North Korea. Last September in Washington, the two leaders underscored the unacceptability of a North Korean nuclear test.

But Secretary of State John Kerry stated in his January 7 conversation with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi that previous approaches to the North Korean problem have not worked and that “we cannot continue business as usual.” The Global Times, a mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, responded by stating that “[t]here is no hope to put an end to the North Korean nuclear conundrum if the U.S., South Korea, and Japan do not change their policies toward Pyongyang. Solely depending on Beijing’s pressure to force the North to give up its nuclear plan is an illusion.”

The now exposed Sino-U.S. gap over North Korea runs deep and extends to at least four critical dimensions:

- Influence: Since China controls the food and fuel lifelines to North Korea, Western analysts see Beijing holding Pyongyang’s fate in its hands. Yet, North Korea snubbed China and exposed its lack of influence by going ahead with a nuclear test that Xi Jinping had opposed publicly and privately. North Korea has taken Chinese support for granted by assuming that Beijing’s geopolitical interests in stability will not permit China to pull the plug. Washington is now pressing Beijing to move in that direction.

- Ideology: It is particularly hard for China to turn on its last ally despite the clear economic and strategic divergences that have weakened the Sino-North Korean relationship for decades. It appears even harder for China to give up the idea that, despite four North Korean nuclear tests, U.S. enmity toward Pyongyang is the root cause of peninsular hostility. This view persists despite U.S.-North Korea negotiations leading to agreements such as the Agreed Framework, forbearance despite continued North Korean double-dealing and renewed negotiation efforts through Six Party Talks even despite North Korea’s first nuclear test, and even seeming indifference to Pyongyang’s provocations under the moniker of “strategic patience” during the Obama administration.

- Instruments: The record of diplomacy with North Korea shows that neither incentives nor efforts at coercion have been successful in inducing North Korean cooperation. Neither has U.S. signaling (in the form of nuclear-capable B-2 and B-52 overflights of the Korean peninsula) worked to draw a line designed to contain North Korean provocations. But China fears that additional pressure will lead to peninsular instability and has moved too slowly to ratchet up pressure on Pyongyang.

- End state: Underlying surface agreement on the necessity of denuclearization is a yawning gap over the type of Korean peninsula that would be acceptable if, as more and more Americans have concluded, the only way to get rid of North Korea’s nuclear weapons is to get rid of the Kim Jong-un regime. China opposes a unified Korea allied with the United States, preferring to maintain a security buffer on the Korean peninsula against U.S. forces. The broader impact of rising competition from the U.S. rebalance and Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea has begun to inhibit prospects for Sino-U.S. cooperation on North Korea. North Korea to date has counted on Sino-U.S. geopolitical mistrust to secure space for its survival.

North Korea’s underlying assumption behind its nuclear gambit is that it can survive and perhaps even benefit from an open geopolitical rift between the United States and China. Sino-U.S. cooperation is costly to North Korea, while a failure to cooperate on Pyongyang would severely exacerbate Sino-U.S. friction and competition. However, if North Korea cannot exploit geostrategic mistrust between China and the United States for its own gain, the assumption behind Pyongyang’s man-made tremors may lead to fatal consequences for the Kim regime.

Scott A. Synder is Senior Fellow for Korea Studies and Director of the Program on U.S.-Korea Policy. This post appears courtesy of CFR.org and Forbes Asia.