The Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) is entering its ninth iteration this month. Known as the world’s largest free literary festival and “the greatest literary show on earth,” the has JLF in a short period of time surpassed all other literary festivals in the world in terms of sheer size. Last year, approximately 245,000 people visited the festival over the course of its five days. For many, the JLF has become an annual fixture and an important pilgrimage in their yearly calendar.

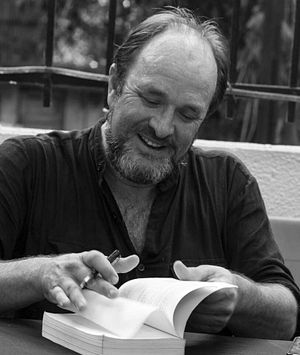

The importance of the festival can be gauged from the fact that almost all contemporary great international writers have descended on Jaipur to be part of the annual literary jamboree. William Dalrymple is not only a prominent face at the event, but also a founding member of the JLF. He plays a crucial role in bringing renowned guests from across the world. Himself a celebrated author and historian, Dalrymple, along with Namita Gokhale and Sanjoy K. Roy have given the medieval city of Jaipur a new identity. The India-based British author believes that such a literary festival not only acts as a chronicler of democracy, but also catalyzes and abets a modern society.

The Diplomat’s Sanjay Kumar spoke with Dalrymple a week before the JLF, which begins on January 21.

What’s new for JLF 2016?

Each year, my list is four-fifths international authors who have never been to the festival before. Out of 70 writers coming the to JLF this year, sixty are here for the first time. All of them are major literary figures from different parts of the world. For example, in fiction, we have Margaret Atwood, a major international star, David Grossman from Israel, and the Booker prize winner, Marlon James. In non fiction, Niall Ferguson and Thomas Piketty are coming. We have an amazing line up.

How different is the JLF from other literary festivals?

I am surprised how different we are from other literary festivals, considering that most of the festivals in India are copies of our model. But there are three which are serious: the Hindu Literary Festival, and the Chennai Times Literary Fest in Delhi and Mumbai. Even they have only three or four international writers but we have seventy. We have twenty times more international writers than any other literary festival in India. They are not only international writers, but they are the greatest names in their fields. We have Oxford and Cambridge alumni, Nobel prize winners, a Pulitzer winner and a whole list of Booker Prize winners. We are also the only festival in India where you have proper place for regional, or bhasha writing. We give a huge space to authors writing in Indian languages other than English. The credit for organizing this goes to my colleague, Namita Gokhale. No literary festival in the country encompasses as wide a range of world literature as well as the linguistic diversity of Indian writing.

How far has the ongoing intolerance debate in India shaped your preparations for the JLF this time?

We have always been very clear on the need for the freedom of speech. A few years ago, when Salman Rushdie was invited, it sparked such a huge controversy that he had to cancel his appearance. But we fought bitterly for his right to come to the JLF. In a situation where three writers have been assassinated in India in recent times, there is an enormous need for solidarity among writers. This is a crucial element of what we do in Jaipur. That said, this is not a new problem. “The Satanic Verses” was banned by a Congress government. Writers have to fight against the government across the globe in a variety of political contexts. This is a very complicated issue; in fact, this is a war that has been ongoing for a long time. Writers versus the state is an old battle. We have sessions where we invite discussion regarding the issue of intolerance and freedom of speech in the festival.

Why have authors like Wendy Doniger, who wrote the book, “The Hindu: An Alternative History,” which became controversial couple of years ago, not been invited?

I am a huge fan of Doniger. I tried to bring her in, but apparently she did not feel comfortable coming here. She told me that she would not be able to visit India for a while.

Do you feel that India is becoming more illiberal and radicalized?

There is certainly a problem of intolerance in India right now. Personally, I also feel the heat sometime. This is especially true on Twitter; if you express an opinion that is critical of the present regime, a right-wing maniac often pounces on you. My experience has not been bad compared to other writers who write in a language other than English. When they express an opinion on subjects which are sensitive to right-wing Hindu groups, they often get harassed. We stand by such authors. However, this kind of criticism isn’t new. For example, Rushdie’s work was banned by the Congress government. So it’s an old debate.