U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, faced with North Korea’s claim to have tested a hydrogen bomb, complained to his Chinese counterpart that China’s strategy toward North Korea “has not worked, and we cannot continue business as usual.” In the wake of last week’s missile launch, presidential candidates from both parties called on China to do more. But American observers may have exaggerated the docility of North Korea toward China from the beginning, according to the diplomatic record of Sino-North Korean relations during the Cold War.

Declassified Cold War-era records from the archives of the former Soviet Union, East Germany, Mongolia, Romania, and others—all former allies of North Korea—reveal that North Korea’s relationship with China has been fraught with tension and mistrust. As early as the Korean War, Pyongyang viewed Beijing’s interference as heavy-handed.

In the late fall of 1950 the so-called Chinese People’s Volunteers, who had taken command of field operations in Korea, vetoed North Korean proposals to continue offensive operations against U.S. and South Korean troops in 1951. Consequently North Korean leaders blamed Chinese military officials for failing to reunify the Korean peninsula, even though Chinese forces had in fact rescued the DPRK from certain annihilation.

During the war disagreements also arose over control of North Korea’s railroad system. Chinese forces prohibited their use for anything other than military operations, including reconstruction after battle lines stabilized, a decision North Korean officials disputed, especially as many trains, standing still, fell prey to U.S. bombs.

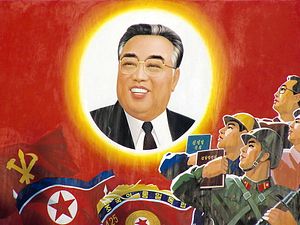

After the war, North Korea’s founding leader Kim Il-sung (grandfather of current leader Kim Jong-un) demoted and arrested key officials in the ruling Korean Worker’s Party (KWP) who had close ties to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), despite the continuing presence of tens of thousands of Chinese People’s Volunteers in the DPRK after the Korean War armistice.

In December 1955, Kim introduced the political ideology of “Juche,” usually translated as “self-reliance,” as a method of minimizing Chinese and Soviet influence on political, economic, and cultural developments. The next year, more pro-Chinese and pro-Soviet party officials were purged for challenging Kim’s autarkic economic development strategies and personality cult at a plenary meeting of the KWP. This time, however, Beijing and Moscow dispatched a joint Sino-Soviet party delegation that forced Kim Il-sung to convene a new meeting, reappoint purged officials, and release two others from prison to accompany the delegation back to China. Decades later Kim was still simmering with resentment in conversations with foreign communist leaders from East Germany, Bulgaria, and Mongolia.

Relations between Pyongyang and Beijing briefly improved in the early 1960s when the North Korean leadership had a falling out with Moscow, whose leadership of the Communist world China was by then disputing. But by the mid-1960s, during China’s Cultural Revolution, Kim Il-sung became a direct target of criticism for China’s Red Guards for allegedly “sitting on the fence” in the ongoing Sino-Soviet split. China’s leaders, who were in disarray, tolerated and even abetted these attacks. Relations deteriorated to the point where the Chinese and North Korean militaries clashed in the vicinity of Paekdu Mountain in 1969. According to a 1973 conversation between Kim and Bulgaria’s Todor Zhivkov, on another occasion Chinese troops crossed into North Korean territory and occupied a town. Kim ordered an attack, but the Chinese slipped back across the border.

Relations showed signs of improving again by the early 1970s, and China even apologized for its behavior, but Kim’s trust in the Chinese leadership was never restored. Kim, during an April 1975 visit to Beijing, reportedly tried to enlist Chinese help in a renewed bid to liberate South Korea. Deng Xiaoping, however, emphasized that China would not commit itself because the PRC was facing the tremendous challenge of promoting socialist economic reconstruction at home.

Deng’s policy of modernizing the Chinese economy led Beijing down a very different path from Pyongyang’s as China abandoned revolution for a place in the existing international system. Especially when trade with South Korea became a priority—even before the end of the Cold War—Beijing’s policy promoted stability in the Korean peninsula.

Since the Cold War, China retains real leverage on North Korea because of North Korea’s economic dependence, even though the countries’ international stances have continued to diverge. Economic leverage, however, does not enable the Chinese leadership to impose policy directives upon North Korea at will—precisely what North Korea most resisted throughout the Cold War. Moreover, if Beijing’s leaders were to use their economic leverage by cutting off aid to North Korea, they would risk economic and societal collapse in the DPRK, which would threaten Beijing’s own and security interests. North Korean collapse would likely lead to a flood of refugees into Manchuria. Moreover, Beijing would not welcome the presence of U.S. troops stationed along its border in a unified Korean state.

Meanwhile the United States has long outsourced its North Korea policy to China, beginning in the late 1970s as Washington prepared to normalize relations with Beijing, declassified U.S. records suggest. This approach reflects a poor understanding of the relationship between China and North Korea, and it also enables China to reassert its traditional hegemony in the strategic region and directly challenge U.S. strategic interests.

More creative diplomatic solutions would use all available instruments, including the United States’ own under-appreciated influence—North Korea has been trying to speak to the United States since 1974. The United States can sit down with foes and hammer out a deal, as is demonstrated by the Iran nuclear agreement, however imperfect. Similar robust engagement with North Korea is needed to prevent the emergence of conditions under which North Korean leaders feel that military adventurism is the most effective way to achieve their diplomatic, political, and economic goals.

Even if the recent test was not of a hydrogen bomb, and the recently-launched satellite is “tumbling in orbit,” the United States must secure an agreement from North Korea to freeze production of all nuclear weapons materials and halt missile tests. And whenever the DPRK cheats or violates agreements—and they will—the United States should not withdraw, nurse its bruised ego, call the North Koreans names, and apply additional sanctions that will hurt the North Korean people by curtailing the humanitarian work of NGOs but do nothing to stymie the further development of nuclear weapons programs since China does little to enforce them. The answer is for the United States to directly engage the DPRK and to maintain pressure.

James Person is deputy director of the History and Public Policy Program and Coordinator of the North Korea International Documentation Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The opinions in this article are solely those of the author.