Four years into the Obama administration’s “Asia-Pacific Rebalance” and on the eve of a tumultuous national election, questions about the coming consistency of U.S. foreign policy are at the forefront of every policymaker’s mind. Yet even without these disruptive factors, there is one area in which the United States should continue to provide coordination, collaboration, and commitment with allies and friends in East Asia: remote sensing and earth observation (EO) platforms.

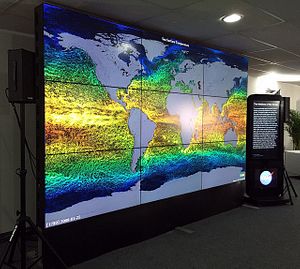

Remote sensing technology and equipment can be generally broken down into platforms, sensors, and sensing systems. Platforms include satellites of all kinds – large satellites, small satellite constellations, and cubesats – as well as manned or unmanned aerial systems (UAS). Sensors are devices attached to a platform that can both detect and respond to environmental inputs, including pressure, motion, heat, light, pressure, moisture, and other forms of energy. Sensing systems can include cameras, videos, mapping, and the telecommunications necessary to relay the data or imagery to end-users.

All of these pieces combine for not only communication and collection capabilities, but are also critical to supporting commercial, military, and political interests. Unfortunately, for the United States, sequestration still hinders prospective activities in the defense enterprise. For that reason, leveraging the dual-purpose use of remote sensing and EO platforms is a smart strategy; when policymakers acknowledge that equipment and the data that equipment gathers can serve both military and civilian purposes, the appropriations process runs more smoothly. The implications are truly widespread, from political intelligence gathering to meteorology and commercial communications to disaster prevention and response.

So why does this area of technology policy matter specifically for the Asia-Pacific? Regional partners like Japan, India, Australia, and South Korea produce a wealth of EO data. The translation and interoperability of this information, however, remains a tremendous challenge, especially given the diversity of capabilities among partners; while Japan is great with sensors and satellite components, India has an evolving launch system currently experiencing beneficial investments. This kind of cooperation is mutually beneficial to the United States and its Asia-Pacific partners because it advances scientific research and shared security interests alike.

Challenges to the “rules of the road” in the South China Sea are obviously high on the priority list for the United States and its Indo-Asian-Pacific partners, and remote sensing and EO technology can play a key role. The Chinese have initiated anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) efforts in the Indian Ocean and the East and South China Seas, impacting a host of both ASEAN and ASEAN Regional Forum members. In response, ASEAN and ARF members are seeking satellite and High-Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) capabilities to provide deterrence. This tension will no doubt place maritime security concerns prominently on the first ever U.S.-hosted US-ASEAN Summit agenda this week.

Non-state threats are at play as well, however. As global megacity projections for 2050 reveal, the proportion of the world’s population living in urban areas is expected to increase, and overall growth of the world’s population is projected to add 2.5 billion people to urban settings – with 90 percent of that increase concentrated in Asia and Africa. States like India, Japan, South Korea, and Australia are vulnerable to meteorological hazards, and remote sensing data and other satellite derived data packages help them to manage these disasters. Disaster risk reduction still requires political will and investment despite the linkages made between natural disasters and economic loss, food insecurity, migration, and political instability.

The United States faces challenges both at home and abroad to its continued efforts at remote sensing and EO collaboration in the Asia-Pacific. Sequestration remains a procurement barrier that must be resolved by the U.S. Congress, and government bureaucracy must continue to navigate information-sharing and overclassification questions. On the international stage, interoperability remains the key challenge; bilateral agreements aren’t enough to combat the Chinese presence effectively or maintain a watchful global eye on potential natural disasters. Instead, a comprehensive regional framework to build on complementary capabilities will be essential for the way forward.

Melissa S. Hersh is a Washington, D.C.-based risk analyst and Truman National Security Fellow. Dr Ajey Lele is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi. Views expressed are their own.