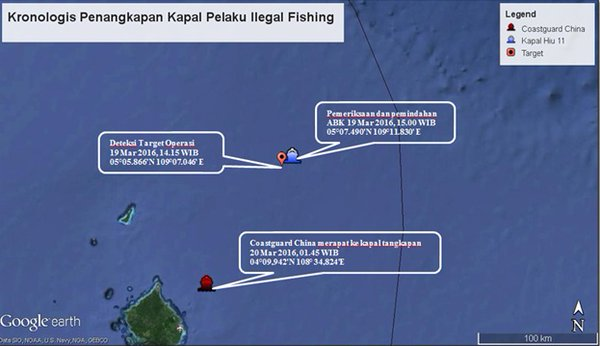

Yet another incident involving a Chinese coastguard vessel and an Indonesian patrol boat has occurred in the vicinity of Indonesia’s Natuna Islands in the South China Sea. Unlike the previous incidents, this time the Chinese coastguard vessel almost intruded into Indonesia’s 12-nautical mile territorial sea off Bunguran (Natuna Besar) Island (see the map below).

The marker and boat icon show where the KP Hui 11 intercepted the Kway Fey. The red dot marks the location where the Chinese CG officers boarded the Kway Fey; the large island to the west is Natuna Besar Island (source: KKP).

The incident started after a patrol boat from the Indonesian Ministry of Fishery and Marine Affairs (KKP), KP Hiu 11, seized a 300-ton Chinese fishing boat, Kway Fey 10078, and arrested her eight crew members for fishing within Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) on the afternoon of March 19. Following a brief inspection, the crews of Kway Fey were transferred over to the Hiu, after which three Indonesian fishery officers from the Hiu commandeered the Kway Fey.

When the Hiu was either towing or escorting the Kway Fey back to base, a Chinese Coast Guard vessel suddenly arrived on the horizon, gave chase, and rammed the Kway Fey, forcing it to stop near the limits of the Indonesian territorial sea shortly after midnight on March 20. By this time, Hiu had already contacted its base for naval assistance. The navy dispatched a rigid-hull inflatable boat (RHIB), since no Indonesian warship is permanently stationed in Natuna.

An Indonesian Navy rigid-hull inflatable boat (far left) confronts a Chinese Coast Guard vessel near Natuna Island. Source: KKP

At almost the same time, a second Chinese coastguard vessel also appeared in the vicinity. To avoid further escalation, the Indonesian officers on Kway Fey decided to abandon the fishing boat and return to the Hiu. Shortly afterward, Chinese Coast Guard officers boarded the Kway Fey to commandeer it away from Indonesian waters. By this time, the Indonesian navy RHIB had arrived at the location and began escorting the Kway Fey out of Indonesia’s territorial sea.

Following the incident, the Indonesian fishery minister, Susi Pudjiastuti, strongly protested against the Chinese Coast Guard actions and vowed to summon the Chinese ambassador in Jakarta. This embarrassing incident might keep the Chinese diplomats in Jakarta busy for a while dealing with the media and public protests, as well as seeking to secure the release of Kway Fey’s crew, who are now in Indonesian detention. The attention has now fallen on when and how the eight Chinese crew members will be released.

Lessons from the Hai Fa incident

It’s telling to compare this incident with the arrest of the Chinese MV Hai Fa last year. At 4,306-tons Hai Fa is the largest foreign illegal fishing vessel arrested since Susi’s ministry began the crackdown. Not only was the Hai Fa fined much less than the total value of her confiscated catch, the vessel was released under controversial circumstances, which prompted Susi to flag Interpol. Had the Kway Fey been successfully detained in Indonesia, Susi wouldn’t have given the vessel a second chance, and certainly would not have repeated the Hai Fa fiasco. Just last week, Susi ordered the sinking of the fishing vessel Viking barely a month after it had been arrested in Indonesian waters; the Kway Fey could have expected a similar fate.

A new approach for Indonesia?

While seemingly escalatory at the tactical level, this incident did not signal a new Chinese modus operandi at the strategic level. China is renowned for using its fishermen as proxies to enforce its nine-dash or U-shaped line claim in the South China Sea, a claim that partly overlaps with Indonesia’s 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone near the Natuna Islands. But the way Indonesia responded to the latest incident was different: the KKP reversed Indonesia’s official tendency to downplay maritime incidents involving Chinese government vessels near the Natuna Islands.

To the KKP, Chinese government support for their fishermen operating in the Indonesian EEZ is clearly unacceptable and even insulting. This time, the KKP “transparently” publicized the tactical details of the Kway Fey incident on social media and in the press. It seems the KKP is trying to draw as much Indonesian public attention as possible to Chinese government complicity in resisting Indonesia’s crackdown against foreign illegal fishing — a crackdown that has gained immense domestic popularity in Indonesia.

At the heart of this incident, however, are Indonesia’s frustrations at the difficulty of retaliating against China’s growing maritime assertiveness in the Natuna Islands, beyond mere diplomatic protests. Undeniably, Indonesia’s consistent rejection of the U-shaped line has neither deterred nor stopped China’s unilateral imposition of its “traditional fishing grounds” within Indonesia’s EEZ.

While the Indonesian government has made promises to boost naval defenses and maritime law enforcement in the Natuna Islands, implementing those plans has become even more urgent now. Unfortunately, time is not on Indonesia’s side. The fortification and militarization of Chinese-occupied features in the Spratly Islands is continuing apace, which will eventually enable Beijing to impose greater sea control over the U-shaped line, including in the waters near the Natuna Islands. These features could also become springboards for Chinese long-distance fishermen to venture further south, escorted by the Chinese Coast Guard.

This incident has presented Indonesian strategic policymakers with a strategic dilemma: to either retaliate with escalation, or continue doing business as usual and see similar incidents repeated in the future. Greater attention from the Indonesian public on the South China Sea disputes could pressure the Indonesian government to raise more and louder protests against Beijing’s actions, and to immediately carry out promises to improve maritime security in the Natuna Islands. However, any sort of retaliation would remain contingent on the price Jakarta is able and willing to pay in terms of a deteriorating relationship with Beijing. The time has thus come for Jakarta to consider alternative strategic options more seriously.

Ristian Atriandi Supriyanto is Indonesian Presidential PhD Scholar with the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Australian National University