Would you simply believe someone’s questionable claims without concrete proof?

For more than three decades, the People’s Action Party (PAP) government in Singapore has been peddling the notion that many Singaporeans vote along racial lines and that this has the potential to trigger a lack of minority representation in Parliament.

This argument forms the basis of the Group Representation Constituency (GRC) electoral scheme the PAP devised in the 1980s. But have Singaporeans ever wondered how the island’s ruling party arrive at its conclusion about racial bias at the polls?

Instead of simply accepting the PAP’s theory as gospel truth, Singaporeans should be asking their government to prove its claims.

Relying on only anecdotal evidence of a supposed problem to devise policy solutions is hardly sound policymaking, and certainly not the kind that would serve Singapore’s national interest.

This issue is not about whether one is pro-PAP or not. Neither is this about whether one is pro- or anti-affirmative action for the Republic’s political arena.

Most importantly, the issue is about whether the PAP’s claims are backed up by facts. If the basis for the GRC scheme is invalid, it raises some uneasy questions.

Have Singaporeans been believing in a myth? Are GRCs a response to unfounded fears? Should the GRC system be abolished if there is no real basis for keeping it?

The most effective, and perhaps only, way of testing the PAP’s voting-bias theory is to observe how Singaporeans vote, by examining election statistical data from every general election since 1959, the year Singapore became a self-governing state.

Voting Along Racial Lines – What It Really Means

Before examining evidence that either confirms or disproves the PAP’s theory of voting bias, let’s see what this theory really means.

For instance, it could mean that even a lifelong PAP supporter would switch his vote to the opposition if the racial profiles of candidates in his constituency necessitate his doing so.

In other words, simply because of a candidate’s ethnicity, voters would actually abandon their loyalty to a political party and switch their votes to another party which they may not trust, without regard to the political views or strengths/weaknesses of competing candidates.

Racially motivated voting could also mean a person would spoil his vote because he neither wants to vote for a minority nor for any candidate from a political party he does not believe is leading Singapore in the right direction.

But since spoilt votes have always formed a miniscule portion of all votes cast in Singaporean elections, we can conclude that such invalid votes have no significant impact on minority representation in Parliament.

Empirical Evidence

Over the past three decades, many have argued against the GRC scheme, pointing out incidents of gerrymandering. But Singaporeans should first seek the answer to this question: Is it true that most Singaporeans vote along racial lines?

Using all election statistical data since 1959, this article provides empirical evidence confirming the veracity of these two statements.

1) The assertion that Singaporeans vote along racial lines is fiction.

2) The assertion that Singaporeans vote along political lines is fact.

Unsolved Mysteries

The path towards the GRC electoral system began in July 1982 when the then Singaporean prime minister, the late Lee Kuan Yew, initially discussed with his right-hand man, Goh Chok Tong, the possibility of ensuring a minimum level of minority representation in Parliament.

At that time, Lee was worried about more Singaporeans choosing their member of parliament (MP) based on race. Lee felt this would lead to a lack of diversity in Parliament.

But GE1980, the last general election before Singapore’s ruling politicians began the journey towards introducing their GRC scheme, produced 18 minority MPs, who filled 24 percent of all seats in parliament.

Herein lies the mystery: Given 24 percent minority representation and with minorities forming approximately 22 percent of Singapore’s population in 1982, how did the Lee Kuan Yew administration arrive at its conclusion on Singaporeans’ voting behavior?

During GE1984, the last general election before the PAP government legalized its GRC scheme in 1988, minority candidates won 31.6 percent of multiracial electoral contests, the highest percentage since Singapore’s independence in 1965.

Here’s another mystery: Against a backdrop of empirical evidence demonstrating that minority candidates were not racially disadvantaged, why did the PAP implement the GRC system?

Talk about being kiasu. The PAP has clearly displayed this typical Singaporean trait through its excessive worries about what it perceives as Singaporeans’ racially motivated voting behavior and seizing the opportunity for affirmative action its unfounded fears have created.

If you think the GRC system is an invalid government policy devised to fight a non-existent problem, you will very likely find many others who think likewise.

Did PAP Misread Singapore’s Pre-GRC Election Data?

Table A: Numerical data from pre-GRC elections (1959 – 1984)

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Year of general election | Proportion of minority representation in parliament | Number of minority MPs | Total number of MPs | Number of multiracial electoral contests | Number of minority victories | Proportion of minority victories |

| 1959 | 35.29% | 18 | 51 | 28 | 16 | 57.14% |

| 1963 | 31.37% | 16 | 51 | 20 | 13 | 68.42% |

|

Singapore became an independent country in 1965 |

||||||

| 1968 | 29.31% | 17 | 58 | 4 | 1 | 25.00% |

| 1972 | 24.62% | 16 | 65 | 20 | 3 | 15.00% |

| 1976 | 24.64% | 17 | 69 | 20 | 6 | 30.00% |

| 1980 | 24.00% | 18 | 75 | 15 | 4 | 26.67% |

| 1984 | 20.25% | 16 | 79 | 19 | 6 | 31.58% |

There was a downward trend in the proportion of minority representation from 1959 to 1984. Could this trend (see Table A, Column 1) have pushed the PAP to hit the panic button? If it had, it would have meant an overly simplistic approach to policymaking – formulating policies based on conclusions drawn from only one election statistic.

A national election is a highly complex process that requires a careful analysis of statistical data if one is to draw valid conclusions on voter behavior.

No one should rush into any judgment that an electoral victory by a candidate from Singapore’s ethnic Chinese majority over a minority must be due to voters’ racial bias.

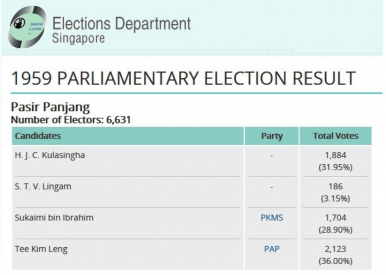

For instance, during GE1959, 64 percent of valid votes by Pasir Panjang residents were split among three defeated minority candidates, while the PAP’s Tee Kim Leng obtained 36 percent (see image below). Clearly, there was no unfair disadvantage attributable to race.

From 1959 (when the PAP first assumed power) until 1984, there were 77 victories by Chinese candidates in multiracial electoral contests. Seventy three of those wins went to the PAP. If Singapore’s ruling party insists that racial bias exists among many voters, it should clarify which of its candidates did not win on merit but through voters’ racialism.

Another important statistic involves minorities defeating Chinese candidates. There were 49 such victories, or 38.9 percent of all 126 pre-GRC multiracial electoral contests, evidence that a candidate’s ethnicity plays little or no part in a voter’s decision at the polls.

The PAP won 117 of those 126 multiracial tilts, proving that whenever voters were asked to make a choice between candidates of different races, they almost always chose the PAP and did so regardless of ethnicity. This is known as voting along political lines.

Why the Downward Trend in Minority Representation?

The preference of most Singaporean voters for the PAP, whatever its candidate’s race, has resulted in this phenomenon – a near-perfect correlation between the proportion of minority representation in parliament and the proportion of minority candidates on the PAP slate. This phenomenon is the reason for the drop in minority representation from 1959 to 1984.

TABLE B

| Year of general election | Proportion of minority candidates in PAP slate | Proportion of minority representation in Parliament | Number of minority PAP candidates | Number of minority MPs in Parliament | Total number of MPs in Parliament |

| 1959 | 33.33% | 35.29% | 17 | 18 | 51 |

| 1963 | 33.33% | 31.37% | 17 | 16 | 51 |

| 1968 | 29.31% | 29.31% | 17 | 17 | 58 |

| 1972 | 24.62% | 24.62% | 16 | 16 | 65 |

| 1976 | 24.64% | 24.64% | 17 | 17 | 69 |

| 1980 | 24.00% | 24.00% | 18 | 18 | 75 |

| 1984 | 18.99% | 20.25% | 15 | 16 | 79 |

Table B shows that the lower the proportion of minorities in the PAP slate of candidates, the smaller the proportion of minority representation in parliament.

Back in the 1980s, the PAP government should have noticed this trend before jumping to a vastly different conclusion about voter behavior and changing the law to accommodate its GRC scheme.

The almost 100 percent correlation is not surprising. This is exactly what one would expect when voters choose their parliamentary representative based on political affiliation, not race, in a situation where one party enjoys overwhelming dominance.

Elections Under the GRC System

The pre-GRC trend of Singaporeans voting along political lines continued after GRCs became a fixture on Singapore’s political landscape. Almost every elected seat since 1988 has been filled by a PAP parliamentarian – 562 out of a total of 585.

Just like during the pre-GRC era, the proportion of minority representation under the GRC system is almost wholly dependent on the proportion of minority candidates on the PAP slate.

This period saw 28 GRC battles involving an unequal number of minority candidates between the two competing parties. If voters were racially biased, they would choose the party with fewer minority candidates, but there were as many as eight victories (28.57 percent) for the party fielding more minorities.

One of those eight wins is a good example of why race is not an issue in Singaporean politics requiring affirmative action such as the GRC scheme.

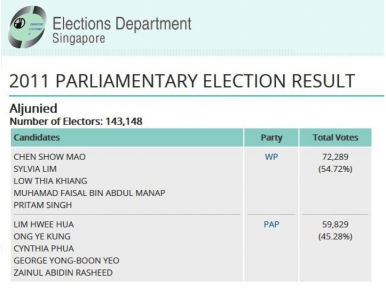

If the PAP theory of racial bias among voters was valid, why did Aljunied residents vote for a party fielding more minority candidates (see image below), especially since they (Pritam Singh and Muhamad Faisal) had no previous parliamentary experience, unlike their opponent Zainul Abidin Rasheed?

One may argue that the 2011 Workers’ Party victory in Aljunied does not necessarily mean racial bias didn’t exist. Rather, this argument might go, there was just too much voter dissatisfaction with the ruling party at that time, causing the tide to turn against the PAP.

But if so, then it means that Aljunied residents’ political concerns trumped any racial bias they might have had, meaning that any racialism among voters was not able to sway the outcome of an election contest.

Multiracial Single-Seat Contests During the GRC Era

Not every minority MP entered parliament through a GRC.

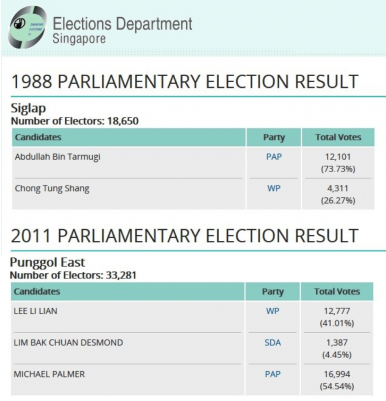

Even when the PAP decided to have one of its minority candidates contest in a single-seat constituency, voters still sent that candidate into parliament instead of picking the opposing candidate from the ethnic Chinese majority (see image below). This clearly demonstrates that race plays no significant part in voters’ decisions.

Of course, there were 28 single-seat victories by Chinese candidates against their minority opponents. But one can easily argue that those results simply reflect the clout that the PAP enjoys in Singapore’s political arena. If the PAP disagrees with that argument, it should reveal to Singaporeans which of its 28 victories had nothing to do with merit.

From whichever angle you look at the Republic’s election data, it’s impossible to arrive at any convincing conclusion that Singaporeans vote along racial lines.

So Many Questions, But No Satisfactory Answers

The PAP says it fears inadequate minority representation in parliament, but what is adequate? If “adequate” means proportional parliamentary representation based on Singapore’s demographics, should there also be affirmative action to bring about “adequate” minority presence in the country’s employment, educational and sporting sectors?

If it is deemed impractical or unnecessary to expect every Singaporean corporation, school or sports team to adhere to a racial quota, why should the GRC scheme be allowed to continue, especially when the very problem the scheme was created to overcome does not even exist?

Michael Y.P. Ang is an independent Singaporean journalist. In 1999, he was among the core group of journalists who helped launch Channel NewsAsia, where he covered sport, entertainment, crime, and the 2001 Singapore General Election. He comments on Singapore’s sporting issues, often through a sociopolitical angle, on his Facebook page Michael Ang Sports.