“I am so glad I went to vote,” Jahan says, a 36-year-old engineer working at the world’s largest gas field in the south of Iran. It was Jahan’s first time at the ballot box, having boycotted all previous elections like many other opponents of the conservative regime.

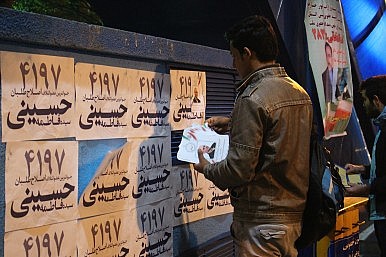

Hope for change persuaded him, as did the mass appeal of influential Iranians on social media calling for people to vote for the “List of Hope,” as the coalition of reformists and moderates were being called.

Political debate is intense at this small election-after party in Sa’adat Abad, one of the more affluent neighbourhoods in the north of Tehran. Besides Jahan, writers, filmmakers and academics debate the future of Iran, drinking home-brewed arrack while listening to Azerbaijani jazz, interspersed with Jacques Brel.

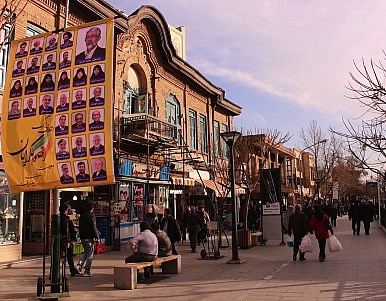

Protest Vote

They all believe these elections will mark the beginning of a more open, freer and economically prosperous Iran. The day after the elections, Saturday, it turns out that the highly educated middle-class is not alone in cherishing this hope, although the turnout might not be quite as high as the reformists had expected. According to the Ministry of the Interior, roughly 62 percent of the electorate cast a vote – a number similar to the previous parliamentary elections in 2012, but lower than the turnout for the presidential elections in 2013.

The elections were a referendum on the pro-Western course of President Hassan Rouhani, who struck a nuclear deal last year with the six world powers. But although the EU and U.S. have lifted some economic sanctions in the wake of the deal, the average Iranian has yet to feel any economic recovery – one reason why many poorer voters did not go to the ballot box.

Speaking with many voters in Tehran, it is striking to hear about the opposition’s priorities. Many voters were not voting for a favorite politician, as most of the best known reformist candidates had been disqualified by the clerics of the Guardian Council, a vetting body consisting of six clerics and six sharia judges. Rather, they were intent on building a force to oppose the conservative regime. “By choosing the least bad candidate, we will gradually vote the most conservative out,” thinks Gulzar, a filmmaker, who like Jahan cast a vote for the very first time.

A Win for Rohani

Official results show significant gains for Rouhani and his allies. In Tehran, moderate reformists took all 30 of the 290 seats in parliament, leaving not a single seat for the conservatives. The “List of Hope” did well in many other cities.

According to the latest results released by the normally reliable Iranian Student’s News Agency, which are still unconfirmed, moderate reformists have won 83 seats in parliament, conservatives 78, and independents 60. Five seats go to religious minorities. The remaining seats will be distributed after a run-off for some cities and towns where candidates could not get the required minimum 25 percent of the votes. The run-off will be held in April.

The reformists also did well in the Assembly of Experts, a panel of 88 clerics tasked with appointing the next supreme leader. In Tehran, they won 15 out of 16 seats reserved for the capital, leaving only one seat for the hardliner Ahmad Janati. Assembly chair Mohammad Yazdi was ousted, as was Mohammad Mesbah Yazdi, mentor of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Reacting to the result, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insisted that “the elimination of these hardliners was an organized attempt by foreigners.”

The Assembly will have 32 new members, among them many moderate candidates, but also some prominent conservatives. Former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a pragmatic centrist who won the most votes in Tehran, tweeted: “The Competition is over. The era of unity and cooperation has arrived.”

A Different Iran?

But what does the moderate reformist victory really mean for the future of Iran? Certainly, Rouhani now has a firm power base in parliament that will enable him to push through a number of economic reforms. In the new Iranian year, which starts March 21, Rouhani promises one million new jobs and GDP growth of between 5 and 8 percent – ambitious plans that have already been criticized as “unrealistic” by analysts. Although the projected economic effects of Rouhani’s policies are still unclear, his latest success certainly increases the chances that he will be reelected president next year.

Although Rouhani might be able to change the economic course of Iran, and influence the position of hardliners, including Khamenei, he will remain powerless in other ways. Military power for example, rests entirely in the hands of the Revolutionary Guard, the elite Iranian military force that is driving policy in Syria and elsewhere.

Most importantly, Khamenei and the Guardian Council can veto every decision the parliament makes.

On human rights, Rouhani faces countless political challenges. Until now, he has not succeeded in freeing opposition leaders Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, who have been under house arrest ever since the contested presidential elections in 2009, after which Ahmadinejad took office. It’s hard to speak about democratic elections in Iran as long as these two fathers of the Green Movement – the silent protests that took place after the 2009 elections, which many believed were a scam – cannot participate. Another worrisome trend is the number of death penalties, which have hit a record high during Rouhani’s presidency.

The reformist Parveneh Salashuri, one of the fourteen female candidates who won a seat in parliament, has high hopes when it comes to women’s rights. “One day Iranian women will decide whether or not to were the hijab, and laws that discriminate against women, especially in divorce and inheritance need to be adjusted urgently,” she said in an interview circulating online. After the run-off parliamentary elections, Iran might even have 22 female parliamentarians, the highest number since the Islamic revolution in 1979.

‘Sham Election’

The question remains how moderate the elected “moderate reformists” in the Assembly of Experts really are. Only 20 percent of the candidates for the Assembly were allowed to stand for election, as most reformists were disqualified by the Guardian Council. This alone ensures that the Assembly of Experts will be dominated by more conservative voices. Moreover, a number of elected members who were backed by both reformists and hardliners have dubious reputations: Mohammad Reyshahri and Ghorbanali Dorri-Najafabadi, for example, are both former intelligence ministers who are accused of organizing the murder of scores of dissidents and anti-government voices. Other elected assembly members have a history of calling for the destruction of Israel and America, and some even have called on civilians to use violence to enforce strict dress codes for women.

Maryam Rajavi, the exiled leader of the National Council for Resistance of Iran, has already called the elections “a ‘sham’: a competition between the incumbent and former officials in charge of torture and executions.”

Jahan sighs. “Democracy does not come overnight But these elections are a step in the right direction, they are the beginning of a long trajectory of slow change.”