Note from the author: It’s April Fools’ Day (the dateline on this story is April 2 because it’s always the future in Tokyo relative to where I’m typing in Washington, DC). April Fools’ Day is by far one of the silliest of Western traditions. This story is real in substance (and references an academic paper published in February 2016) even if the word “unicorn” might be more of a clickbait headline trick (which I acknowledge I am also indulging in).

On with the story.

A friend chastised me earlier this week for neglecting to report on what he called the “real stories” that affect Central Asia. He was, of course, talking about the groundbreaking news that a unicorn fossil had been discovered in Kazakhstan. Sharing an article from the fantastic meme-factory of my youth, Cheezburger.com, he said they “beat you to what might be the greatest story to come out of the *stans ever.”

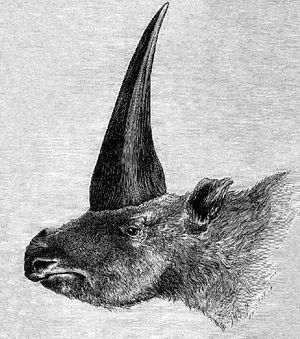

The short post–itself taken from a US News story, which was based on a Phys.org story and was also picked up on by the Guardian–did include a link to a real research paper by a trio of Eurasian paleontologists which concerns the Elasmotherium sibiricum. The Elasmotherium was a genus of giant rhinoceroses and it seems that the Kazakh steppe may have been their last refuge.

The paper, published by the American Journal of Applied Science, addresses “The Quaternary Mammals from Kozhamzhar Locality.” Less scientifically stated, the article looks at the sediment around fossils of mammals found in Kazakhstan’s Pavlodar Region from the Quaternary period (which started 2.6 million years ago and is ongoing). The analysis by the three scientists–two from Tomsk State University and one from Pavlodar State Pedagogical Institute, including an assist on radiocarbon dating from Queen’s University Belfast–indicates that the Siberian version of the Elasmotherium might not have died out 350,000 years ago as previously believed.

One of the scientists, Andrei Shpansky, told Phys.org, “Most likely, the south of Western Siberia was a refúgium, where this rhino persevered the longest in comparison with the rest of its range. There is another possibility that it could migrate and dwell for a while in the more southern areas.”

The study indicates that the mammal may have walked through Eurasia as recently as 29,000 years ago and one of their conclusions recommends that fossils presently believed to be ancient–extinct between 50,000-100,000 years ago–be radiocarbon dated and studied again.

“Our investigations into the Kozhamzhar occurrence showed that biostratigraphic interpretation of the geological age of the alluvial Quaternary deposits is highly complicated,” the paper says. In layman’s terms, this is an argument that the interpretation of fossil ages based on the rocks in which they are discovered is complex. As science has progressed, it is important to reevaluate previous interpretations. Shpansky told Phys.org that this has implications for how scientists understand natural processes: “Understanding of the past allows us to make more accurate predictions about natural processes in the near future—it also concerns climate change.”

While not a unicorn in the modern interpretation of the mythological creature–a graceful horse-like creature with a spindly horn–the Elasmotherium sibiricum’s single tusk may have informed regional legends. If, as the scientists propose, it was still walking around 29,000 years ago it might have passed early modern humans eking out their own existence on the steppe. And that’s how unicorn legends are born.