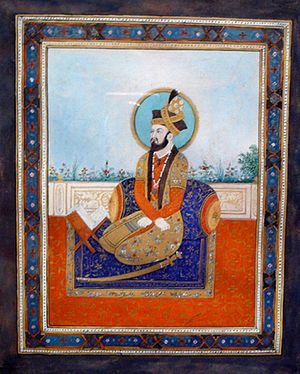

Last year, I reviewed the first volume of The History of Akbar, a 16th century chronicle of the reign of the Mughal Emperor Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar, authored by the Emperor’s vizier, Abu’l Fazl. The tale continues in a new release this year, also from the Murty Classical Library of India from Harvard University Press. The History of Akbar, Volume 2, which, like the first volume, is translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, features the text in both the original Persian and an English translation.

As with the first volume, the second volume is readable and interesting, with many tidbits that delight the reader, though some background in the history of South and Central Asia might be useful. I enjoyed discovering, for example, that the modern city of Jalalabad in Afghanistan “bears [Akbar]’s glorious name (35).” Other prominent cities in South Asia named after Mughal emperors include Aurangabad in Maharashtra and Shahjahanabad (old Delhi). Despite being packed with information and details of battles, journeys, and familial relations, this book, like the first volume, does not contain the directness and simplicity of the memoirs of the founder of the Mughal Emperor, the Baburnama, partially because it is somewhat of a hagiography.

The second volume starts off right where the first ended. Despite being a history of Akbar, it contains the histories of his father and grandfather’s reigns. The first volume focused mostly on the Emperor Babur, while this second one on Humayun. The second volume begins with the exile of his father, Humayun, from India, after a revolt. Akbar was born during this time. In the meantime, Humayun’s holdings in today’s Afghanistan (Kabul, Kandahar, and Badakhshan) ended up in the hands of his brothers–Kamran, Askari, and Hindal–who were of dubious loyalties. Humayun, fleeing for his life to the Safavid Persian Empire, ended up leaving Akbar behind in Afghanistan where he is brought up by his uncles. Humayun’s sojourn in Persia was historically important because it led to enormous direct Persian influence–he brought back thousands of Persian literary and military figures to India–in the Mughal Empire (its high culture was already Persianized, but the major element of the empire up to this point was Central Asian Turkic).

The book picks up as Humayun, accompanied by Persian troops, starts retaking his former holdings from his brothers in 1545, starting with Kandahar, which he initially turned over to the Persians under the son of the Shah, but ultimately keeps after the son dies and complaints of those troops terrorizing peasants and tribesmen. Kandahar ultimately remained a bone of contention between the Mughals and Safavids for over a hundred years. Over two hundred pages, the meat of the book, are spent on the various battles and conquests Humayun undertakes in Afghanistan, while the young Akbar grows up (having been recovered by his father). This section can be quite interesting because it allows the reader to understand Afghanistan through the historical lens (many of the same players are active today, including Hazara, Tajik, and Pashtun groups). Humayun’s brother Kamran is in particular singled out for criticism during this section and indeed, despite constantly losing Kabul or being captured, he continued to fight unceasingly against his brother and the weary people of the region. While Askari also was disloyal to Humayun, Hindal their fourth brother became loyal for life. What is touching is Humayun’s continued forgiveness and pardoning of his brothers, despite defeating and capturing them multiple times; in this age, it was common for brothers to be executed for rebellion.

One of the most charming things about this book is that it contains many couplets and poems composed on the spot by various individuals, as they go about the business of war and peace. Persian poetry was the primary way by which elites of Humayun and Akbar’s time and place expressed their feelings succinctly. My favorite, which I found especially deep, comes from Humayun after his brother Hindal dies in his cause in a battle against Kamran (352-353):

فلک چشم از صبح روشن نکرد

که شام از شفق خون بدمان نکرد

Never has the celestial sphere opened its bright eye of morning

that in the evening its skirt was not bloodied by sunset.

Eventually, Humayun does resolve his problems, and the book swings back in its last 50 or so pages to events that occurred in Hindustan during his absence there, namely its alleged misrule under the usurping Sur dynasty and the deeds of the Hindu general Hemu. Led by the highly able general Bairam Khan and helped by chaos in India, Humayun’s forces easily reconquered his former dominions in India in a short, almost battle-free campaign in 1554-1555. Considering the fact that this laid the groundwork for continued Mughal domination of the subcontinent for over two centuries, instead of Mughal rule just being a passing fluke, it is somewhat disappointing that so few pages are spent on Humayun’s return to Hindustan. The second volume of the chronicle ends shortly afterwards, with the death of Humayun in 1556 from a staircase fall, and the enthronement of his son, Akbar.

All in all, the second volume of The History of Akbar is an interesting and valuable primary source narrative on the origins of one of history’s most consequential empires. While parts of the chronicle can drag, being lists of names or the like, for the most part it is readable and moves at a reasonable pace. The first two volumes published by the Murty Library contain together the first tome of Abu’l Fazl. The second tome of Fazl’s work focuses on Akbar’s reign while the third time, also known as the A’in-i Akbari is an account of the organization and administration of the empire. I look forward to the next few volumes of The History of Akbar from the Murty Library, where the story of Akbar, one of India’s most interesting rulers, will be told in great detail.