Last Monday was the 101st anniversary of the storming of the beaches of Gallipoli by Australian and New Zealand troops, many of whom would lose their lives to Turkey fire in the doomed campaign. It’s a war anniversary still very much celebrated in Australia in the form of Anzac Day (“Anzac” standing for Australia and New Zealand Armed Corps).

Thursday marked a very different anniversary, not a celebration of brave and bloody defeat, but a day to remember the 35 killed and 23 wounded when 28-year-old Martin Bryant opened fire in a cafe at Tasmania’s historic Port Arthur Prison 20 years ago.

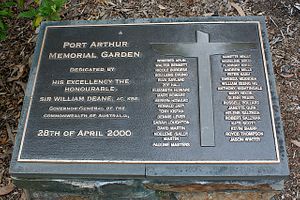

A memorial service was held at Port Arthur, with survivors and their families gathered as Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull gave an address. Former Prime Minister John Howard was in attendance. Memorial services were held in cities across the country. Bryant’s act was not the first mass shooting in Australia, but its horrific scale was unprecedented.

Turnbull began by remembering the dead and the heroism of those attacked, from parents protecting children to the first responders at the scene. But he also noted the sweeping gun laws that changed the nation.

Australia’s worst mass murder prompted immediate change and upheaval. Conservative Prime Minister John Howard, who had taken office less than two months earlier, immediately instituted the biggest gun buyback the world had seen. That buyback and immediate action after such a deeply horrifying event is remembered around the world still, and has been noted after several mass shootings in the United States. The photos of mountains of guns were just as memorable, with the weapons numbering close to 700,000. All automatic and semiautomatic rifles and shotguns were banned and a 28-day cooling off period instituted for purchasers.

Howard’s decisive action and fearless stance against the gun lobby has been praised (though in Australia the power, both political and cultural, of the National Rifle Association of the U.S. would be unimaginable) and he has stuck to his stance ever since, telling U.S. broadcaster CBS in March that, “It is incontestable that gun-related homicides have fallen quite significantly in Australia, incontestable.” He also said, “The hardest things to do in politics often involve taking away rights and privileges from your own supporters,”

And there has not been “another Port Arthur” in the two decades since. However, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) Fact Check (it is worth reading the whole thing) suggests the facts and figures are a little more nuanced than the former prime minister believes: “While it is accurate for Mr. Howard to assert that gun-related homicides and suicides have dropped since his reforms were implemented, there is more to it,” it said. Some studies have suggested that as overall support for suicide prevention has increased it is not demonstrable that a firearms ban alone has been responsible.

Dr. Suzanna Fay-Ramirez, a criminologist at the School of Social Science at the University of Queensland, told the ABC “In light of the broader societal factors that may be influencing the crime rate, Australia’s gun reforms are likely part of the reason we have seen a sustained decrease.” There have been many studies treating data differently or looking at different facts, one reason why 20 years on there is no consensus among researchers despite a strong narrative linking the buyback to a drop in all forms of gun-related deaths.

But what Port Arthur and the subsequent muscular response did do was instill a general dislike of guns in large sections of the Australian community. (Amusingly summed up by Australian comedian Jim Jefferies here.) While hunters and those on farms have little fear of them and some politicians such as Independent Bob Katter and Liberal Democrat David Leyonhjelm (whose stance is Australia’s answer to Libertarianism) are pro-gun, most Australians are not. A 2015 report by Essential Research (page 10) found that “45% think Australia’s gun laws are not strong enough and 40% think they are about right. Only 6% think they are too strong.”

Forty-five percent wishing for even tighter restrictions is no small number.