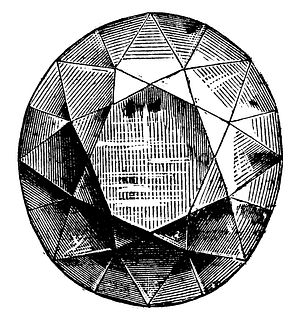

Last year, a storm erupted over the assertion by an Indian politician, Shashi Tharoor, that Britain ought to return the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond to India. Afterwards, a private advocacy group, Mountain of Light, began legal proceedings in a British court to have the diamond returned to India, a move opposed by the British government.

While I agreed at the time that it would have been a positive gesture, from a public relations perspective, for Britain give the diamond to India because of the strong emotions it elicits in India, there are several reasons such a return is difficult to contemplate.

The diamond has a long history of exchanging hands, almost always through conquest. This makes it hard to argue that the most recent exchange of the diamond, to Britain, was a special case. Furthermore, it makes it difficult to establish ownership of the diamond, with the present day countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran all having some sort of claim on the diamond. The original owner of the diamond is a local medieval state in south-central India, the Kakatiya Kingdom, that no longer exists.

This is important because it has legal implications. The main question at hand is whether there is a legal case to be made for the return of the diamond to India. While many would argue that the issue of the diamond’s return is more a matter of right or wrong than legalities, upholding and following legal procedure in this and related cases of international property disputes is of utmost importance.

To do otherwise would open up a Pandora’s box, as British Prime Minister David Cameron has argued, of arbitrary and chaotic claims and counterclaims all over the world on a variety of disputes, many of which would be anachronistic. In a similar case, Greek courts concluded that they would not have a strong argument for regaining the Elgin Marbles, taken from Ottoman-ruled Greece by the British, because of a statute of limitations and the fact that the transfer was legal at that time.

It seems as though some figures in the Indian government have come to the conclusion that there is no legal case to be made for the return of the diamond, however distasteful this may be to them. Whatever the morality of the ownership of the diamond or the conditions by which it came to Britain–the last owner before the British crown, Duleep Singh, is often thought to have gifted it to Queen Victoria under duress–it cannot be definitely proven in a court of law that the diamond was “stolen.”

The solicitor general for the Indian government, Ranjit Kumar, said on Monday that the diamond was “neither stolen nor forcibly taken,” in response to a case being heard by the Indian Supreme Court as to whether it should direct the Indian government to retrieve the diamond.

Nonetheless, the court is still considering the issue, as it does not want to close the door for future attempts to bring back items that once belonged to India.

Moreover, according to CNN, a statement by the Indian Ministry of Culture on Tuesday said that the solicitor general’s views were not those of the Indian government and it “reiterated its resolve to make all possible efforts to bring back the Koh-i-Noor Diamond in an amicable manner.”

It should be noted that the Indian government has retrieved several ancient artifacts from Germany, Australia, and Canada with the cooperation of governments there and without the need to initiate legal proceedings. However, in many of those cases, the artifacts in question were actually stolen by art thieves and there was no question over whether India had a right to them.

Untangling disputes from colonial times, where ethical and legal issues are tangled, is a more difficult task.