This article was originally published on FiveThirtyEight on April 14, 2016. It is reposted here with kind permission.

In early May 2012, seven months after announcing American intentions to make a diplomatic pivot to Asia, Hillary Clinton went to India. Over three days, the secretary of state met with officials in the eastern city of Kolkata and in New Delhi to press them on oil and trade concerns. The visit drew acclaim from observers, including Walter Mead, an influential academic and editor at large for The American Interest, a foreign policy magazine, who was inspired to pen a column on what he called the administration’s grand strategy in Asia. “The deepening US-India relationship is a key piece in a very elaborate program. Ever since President Obama announced a ‘pivot’ to Asia and Secretary Clinton declared this to be ‘America’s Pacific Century,’ Washington’s Asia policy has been firing on all cylinders,” Mead wrote.

Jacob Sullivan, Clinton’s deputy chief of staff at the State Department (and now the top foreign policy adviser to her presidential campaign) emailed Mead’s article to his boss. “This is a terrific piece and well worth the trip to India to produce!” he wrote.

Clinton’s reply was short and did not acknowledge Mead’s effusive praise for the administration’s renewed focus on Asia: “Remind–didn’t we, not the WH, first use the ‘pivot’?”

President Obama made clear early in his presidency that Asia would be a priority, referring to himself as the “first Pacific president” in a 2009 speech in Tokyo in which he also stressed that the days of American apathy toward regional multilateral institutions had passed. But it was Clinton who seems to have been the first to publicly use the buzzword “pivot.” She did so three times in an October 2011 Foreign Policy article on the administration’s plans for “America’s Pacific Century” that is considered the codification of the strategy.

The pivot came to permeate the entire U.S. government’s approach to foreign policy, from Clinton’s time in office through Obama’s second term. Its components were diplomatic, economic and military — stretching from Foggy Bottom to Beijing, from the Pentagon to Tokyo. Claiming credit for it was important to Clinton, who wanted to prove that her role in crafting U.S. foreign policy went beyond implementing her former rival’s ideas.

Foreign policy in general and Asia policy in particular have been fairly minor parts of Clinton’s campaign so far, and the now-preferred word “rebalance” (or her term, “pivot”) hasn’t featured on the campaign trail. Yet her involvement in the creation and implementation of the overall rebalance strategy forms a core piece of her foreign policy credentials as she runs for president; Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution has called the pivot to Asia her “chief great-power legacy.”

There are some signs the rebalance is falling short of ensuring U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific: A recent report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies commissioned by Congress argued that “the administration’s rebalance effort may be insufficient” to secure American interests in the region. Clinton herself has pushed back against one of the major diplomatic and economic initiatives in the region, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, after spending years working on it as secretary.

The Clinton campaign did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this story, but many of her campaign promises on foreign policy — from “holding China accountable” to boosting America’s role in the global economy — tie back into her interactions with Asia while secretary of state. The pivot is larger than Clinton and has lived on after her departure from the State Department, but her role in defining its parameters and objectives provides key clues to how she might approach the Asia-Pacific region if elected president.

***

In reality, the policy was less of a sharp turn than the jazzy word “pivot” implies and more of an astute shift to follow global winds. (In 2012, it was rebranded to the more diplomatic-sounding “rebalance” to avoid the implication that the U.S. was abandoning its commitments elsewhere or had been ignoring Asia previously.) Put simply, any wise American policymaker acknowledges Asia’s sheer economic weight and corresponding geopolitical heft.

When Obama took office, U.S. trade and business ties with Asia had been growing at astounding rates for two decades as the economies of China and India — the world’s two most populous states — kicked into high gear. In 2008, China’s GDP was worth $4.6 trillion in today’s dollars, according to the World Bank. By the end of 2014, it was worth $10.4 trillion — a nearly 130 percent increase in six years. India’s growth over those six years looks positively sedate by comparison, even though it grew by 65 percent to $2 trillion. And China and India are just two examples — even amid a growing global slowdown, the International Monetary Fund predicts that the economies of the Asia-Pacific region, taken together, will grow by 5.3 percent in 2016, well above the projected global growth rate of 3.2 percent.

On the security front, despite headlines over the past few years dominated by Russian adventurism in Ukraine, Iran’s nuclear program and the rise of the Islamic State group, it is China — a rapidly rising power seeking to carve out a global leadership role for itself — that poses a challenge to both U.S. military pre-eminence and global leadership. China’s large-scale land reclamation and aggressive patrolling in disputed waters in the South China Sea, in particular, have sparked concerns about Beijing’s desire to reshape the Asia-Pacific region to better suit its needs.

In addition to economic considerations, these strategic concerns are a major reason why, as Obama put it in a November 2011 speech before the Australian Parliament, “the United States will play a larger and long-term role in shaping this region and its future.”

***

The groundwork for the rebalance was laid less than a month after Clinton took office in 2009. She made the unusual choice of Asia as the destination for her first trip abroad as secretary of state, which no secretary had done since Dean Rusk visited Thailand in 1961. Clinton’s February 2009 trip included visits to not only firm U.S. allies Japan and South Korea, but also China and Indonesia, demonstrating the Obama administration’s emphasis on forging new Asian partnerships.

Walter Lohman, director of the Asian Studies Center at the Heritage Foundation, said in an interview that the rebalance was about “trying to set the context, the framework for pursuing American interests” in the Asia-Pacific region. That involved a particular emphasis on building up diplomatic relationships and forums for pursuing U.S. goals.

On that first trip abroad, Clinton’s meeting with the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations secretary general in Jakarta, Indonesia, would have the most lasting significance. At the time, the United States had not yet acceded to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia that would allow it to join the East Asia Summit and fully engage with ASEAN in areas including economic relations and regional security issues. Jeffrey Bader, former senior director for Asian affairs on Obama’s National Security Council, called the treaty a “feel-good agreement with no binding obligations” in his 2012 book on Obama’s Asia policy — but it would give Washington a seat at the table in regional discussions.

Signing the treaty was a major goal for Clinton. As she recalled during aspeech at the Brookings Institution last September, “The rebalancing to Asia, otherwise known as ‘the pivot,’ was in response to the very real sense of abandonment that Asian leaders expressed to me.” The Jakarta trip was meant to convey a renewed American commitment, and she became the highest-ranking U.S. official to ever visit ASEAN headquarters. The association’s secretary general, Surin Pitsuwan, said Clinton’s visit showed “the seriousness of the United States to end its diplomatic absenteeism in the region.”

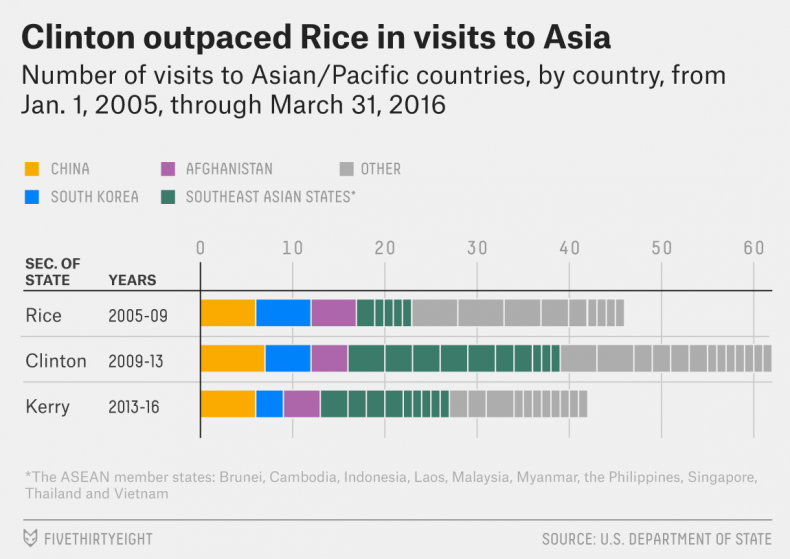

As the adage holds, 90 percent of success is showing up — and show up in Asia was exactly what Clinton did. In her four years as secretary, she made 62 visits to Asian countries, accounting for more than a quarter of all of her trips abroad. Condoleezza Rice, Clinton’s predecessor, made 47 during her four years as secretary. Not only did Clinton make more visits, she also visited the region more widely. Rice traveled to 18 Asian countries; Clinton visited 26. Rice never visited Cambodia or the Philippines, and she visited Indonesia twice. Clinton made three trips to Cambodia, two to the Philippines and four to Indonesia — underscoring ASEAN’s centrality to the rebalance strategy.

Chart Credit: FiveThirtyEight.Reposted with permission.

Initiatives started during Clinton’s tenure — in addition to the U.S. engagement with ASEAN and the East Asia Summit, there was a new bilateral Strategic and Economic Dialogue with China — helped drive many of her successor’s visits to Asia as well. John Kerry attended the ASEAN Regional Forum and East Asia Summit in 2013 in Brunei, and Obama attended the East Asia Summit in 2014 in Myanmar and 2015 in Malaysia. From his swearing-in in February 2013 through this March, Kerry has made fewer trips to Asia than Clinton (42) but has visited almost as many countries (23) in less time.

Meanwhile, the Strategic and Economic Dialogue became the premier annual venue for high-level bilateral talks with China, bringing Clinton and then Kerry to Beijing every other year, when it was China’s turn to host. The new talks upgraded the Bush administration’s premier dialogue with China, which had focused only on economic issues and was chaired by the Treasury secretary. In his book “The Obamians,” James Mann writes that the dialogue was expanded to include political and security issues in part so that Clinton could act as co-chair.

Notably, it was Clinton who definitively expressed the U.S. position on one of the most flammable security issues facing the region: maritime disputesover islands, reefs and shoals in the South China Sea claimed (in part or in whole) by Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. China claims nearly all of the features and — of perhaps more concern — much of the open sea between them. In the past four years, China has become more assertive in patrolling the disputed waters and warning ships and aircraft from other states away from its claimed territory, actions Washington sees as a threat to freedom of navigation. Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates wrote in his 2014 memoirs that Clinton was “very much in the lead” when it came to advancing the U.S. strategy toward the South China Sea, a role that today is largely handled by the Defense Department.

Even before the official rollout of the rebalance strategy, Clinton made it clear that the U.S. would take a hands-on approach to the disputes. In remarks made on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 2010, Clinton laid out the bullet points that still form the crux of the U.S. position today: an emphasis on freedom of navigation, respect for international law, U.S. opposition to coercion and support for negotiated settlements. At each ASEAN meeting since, the United States has raised concerns over the South China Sea and other regional issues — much to the dismay of Chinese pundits, who tend to view the pivot as containment by another name.

U.S. participation in regional talks quickly became the expectation rather than the exception. In 2011, Obama became the first American president to ever attend the East Asia Summit. Two years later, he decided to skip the annual gathering in order to better deal with the government shutdown in Washington. Critics fretted about the implications for American influence, claiming that Obama’s absence effectively gave Chinese President Xi Jinping carte blanche to set the agenda. In two short years, attendance at the summit had gone from a diplomatic first — achieved under Clinton’s guidance — to a necessity for defending American interests in the region.

***

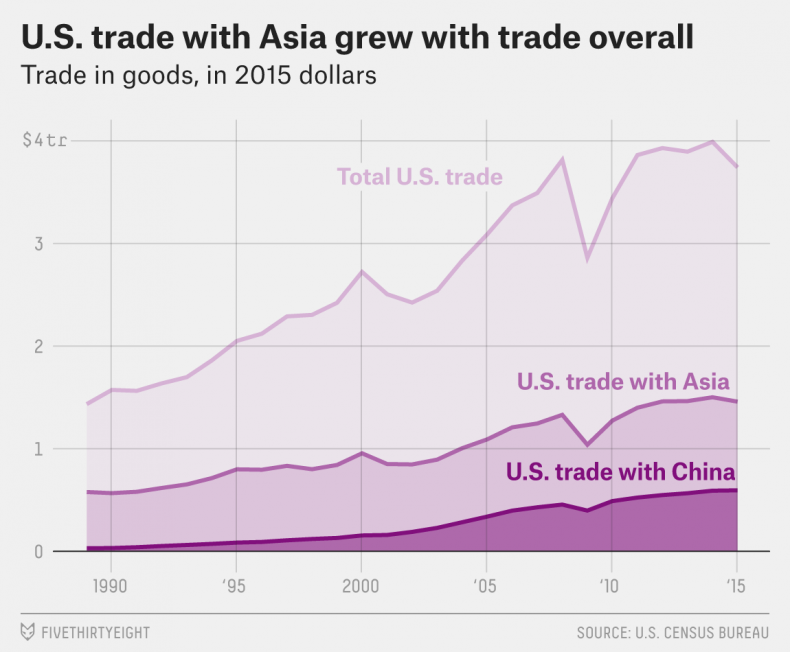

One of the undergirding arguments for increasing diplomatic engagement with Asia is trade and economics. Asia has some of the world’s largest nations and fastest-growing economies, so trading with countries in the region is unavoidable. Other branches of the administration have led trade efforts of their own — most notably the Commerce Department and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative — but the diplomatic swath Clinton cut with her repeated visits cleared the way for continued negotiations on one of the most ambitious trade agreements in history, covering 40 percent of global GDP: the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Chart Credit: FiveThirtyEight. Reposted with permission.

U.S. trade with the world was rising ahead of 2009, when the bottom fell out as a result of the U.S. financial crisis and ensuing Great Recession. Toward the end of 2008, many global economies were falling into recession, including many in Asia. U.S. trade in goods contracted worldwide by 25 percent from 2008 to 2009. The drop in 2009 is obvious in the chart above: It’s literally a cliff-drop.

Trade with Asia in 2009 accounted for 36 percent of U.S. global trade in goods and likewise felt the fall, dropping $291 billion from 2008 to 2009 (in 2015 dollars). But it recovered quickly, jumping back by $235 billion from 2009 to 2010. By 2011, U.S. trade with Asia was back on track, surpassing pre-2009 trade. As of 2015, trade with Asia accounted for 39 percent of U.S. global trade in goods, ahead of North America (30 percent) and Europe (22 percent).

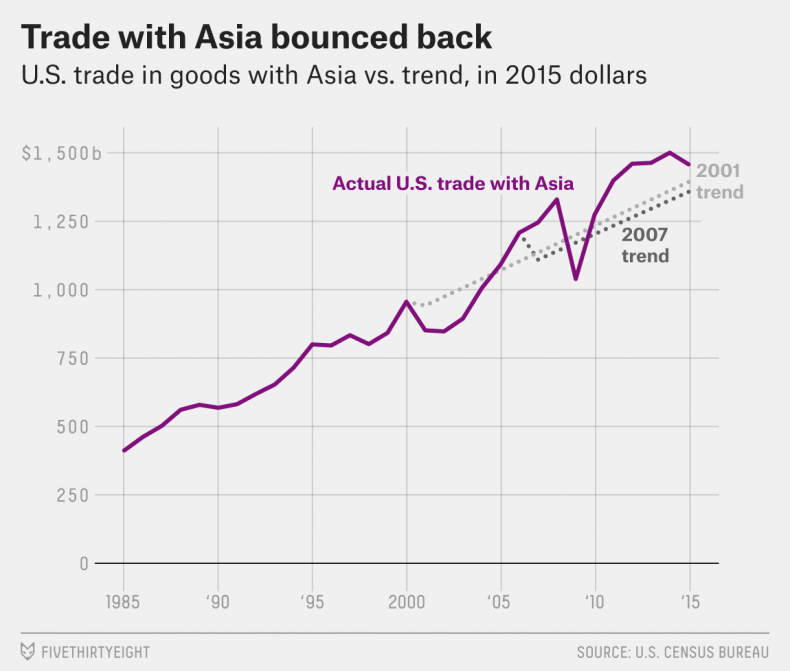

To more easily see the crash and strong recovery, we can take a simple look at actual U.S trade in comparison with expected trends using linear regressions of previous growth. (Although growth in trade is not necessarily linear, for forecasting purposes linear regression can be helpful. Assuming that growth will continue, a linear regression at least gives a baseline for that growth over a certain period of time.)

In the following chart the purple line is actual U.S. trade with Asia through 2015. The light gray dotted line represents an extrapolated trend from 1989 to 2000. The dark gray dotted line repeats this extrapolated trend with data from 1989 up to 2007. While U.S. trade overall has rebounded since the recession, Asia trade has more than rebounded to narrowly exceed earlier trends.

Chart Credit: FiveThirtyEight. Reposted with permission.

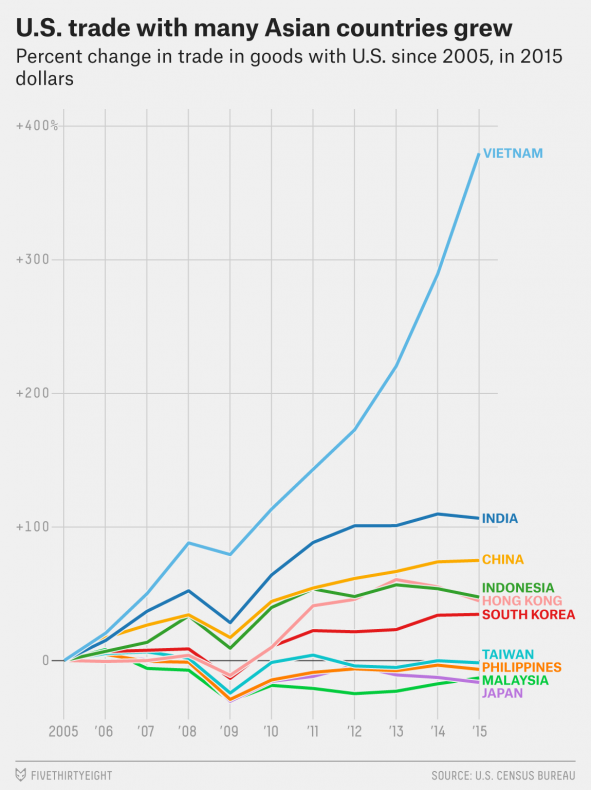

Trade, a cornerstone of Clinton’s diplomatic push in Asia, recovered rapidly with most Asian states after the 2009 crash. For some, such as China and India, 2009 looks like a notch in an otherwise gentle curve upward.

Chart Credit: FiveThirtyEight. Reposted with permission.

The pivot had noticeable impacts on trade elsewhere in the region. For many Asian countries, trends in trade with the U.S. were generally positive before 2009, were interrupted by the crash, and then recovered as expected or better, for example in South Korea, Indonesia and Vietnam. Malaysia and the Philippines had both experienced a period of stagnation or decline in trade with the U.S. but saw growth after the crash and the pivot. In the case of Hong Kong, trade had leveled out but spiked after 2010.

The trends for smaller Asian trading partners — such as Brunei and Mongolia — are decidedly more volatile, but this tells us less about overall U.S. Asia policy. Smaller volumes of trade are prone to much more exaggerated fluctuations — they are often concentrated in one or two industries and involve only a few companies. A massive investment or aid program disbursement in one year can cause a spike that isn’t tied to a sustained trend.

Five of the United States’ top 10 goods trading partners in 2015 were in Asia: China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and India. In 2015, China finally unseated Canada as the United States’ largest partner, accounting for nearly 16 percent of U.S. trade in goods on its own. China accounts for 41 percent of U.S. trade with Asia.

After the pivot, American trade and engagement with Asia broadened, particularly with the ASEAN states that formed the core of Clinton’s diplomatic push — Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia — and South Korea, with which the U.S. signed a free-trade agreement in 2012.

Further gains in U.S. trade and economic engagement in Asia, the administration and a number of economists have argued, are predicated on taking down the remaining barriers to trade. Nothing has been branded as more important to achieving that goal than the Trans-Pacific Partnership, an agreement among 12 nations representing nearly 40 percent of global GDP. Negotiations on the TPP predate the Obama administration, having begun in September 2008, but the Obama administration took the initial idea of the U.S. joining an existing partnership (among Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore) and expanded it into a grand economic vision involving 12 Pacific Rim countries.

As secretary of state, Clinton pushed the TPP negotiations forward by selling the agreement politically and diplomatically across Asia while U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk handled the negotiation details. Clinton spoke numerous times during her tenure in support of the TPP and of its expansion to include Vietnam and Japan. In speech after speech, she referred to the TPP as “an innovative, ambitious multilateral free-trade agreement” (2010), a “very exciting opportunity” (2010) and a “cutting-edge, next-generation trade deal” (2011). In a 2012 lecture at the U.S. Naval Academy, Clinton outlined the intertwined importance of defense, diplomacy and development. In that speech, she made the case for the TPP:

This agreement is not just about eliminating barriers to trade, although that is crucial for boosting U.S. exports and creating jobs here at home. It’s also about agreeing on the rules of the road for an integrated Pacific economy that is open, free, transparent and fair. It will put in place strong protections for workers, the environment, intellectual property and innovation — all key American values.

In that speech, Clinton agreed, as Obama and others have often insisted, that the TPP is more than a trade deal; it is a symbol of continued U.S. leadership in a vital region. To many analysts, the success or failure of the TPP defines the success of the rebalance as a whole. Lohman, of the Heritage Foundation, points to the potential rejection of the TPP as a factor that could “damage” the entire rebalance strategy. “The whole economic side of the rebalance is all tied up in the TPP,” he said. “Without the TPP, you don’t have a full rebalance to the region.”

Unfortunately for its supporters, the deal looks to be in jeopardy because of skepticism and intransigence in Congress and Clinton’s own reversal of her position on the pact. The TPP is one area where the policymaking record of Secretary Clinton diverges from the politicking rhetoric of Candidate Clinton. While on the presidential campaign trail, Clinton has pulled back from supporting the TPP, saying the agreement — in the final form agreed to in October 2015 — does not meet her standards. “I still believe in the goal of a strong and fair trade agreement in the Pacific as part of a broader strategy both at home and abroad, just as I did when I was secretary of state,” she said in a statement in October. “But the bar here is very high, and, based on what I have seen, I don’t believe this agreement has met it.”

The TPP has garnered bipartisan support — it’s a policy put forth by a Democratic president that has had more support from congressional Republicans than congressional Democrats. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, however, recently pushed back against the idea of putting the TPP up for a vote before next year, saying, “With both the Democratic candidates for president opposed to the deal and a number of presidential candidates in our party opposed to the deal, it is my advice that we not pursue that, certainly before the election. And some would argue that it’s not fair to the voters for them not to consider what you might do after the election.”

Obama may yet send the TPP to Congress for consideration before November — laying the deal’s fate in the hands of the present legislature and not on the table for the next president. Nonetheless, congressional dysfunction could kill the deal just as easily as Clinton’s flipping on the issue.

***

he idea that the rebalance is not living up to expectations continues to dog the Obama administration. A congressionally commissioned study of U.S. defense policy in Asia, released in January by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, expressed concern that the rebalance, in practice, isn’t enough to defend U.S. interests in Asia. One of the major criticisms was that the Obama administration did not go far enough in laying out the specifics of its strategies and goals for engaging the Asia-Pacific, making the “rebalance” less effective than it could have been.

Some of this may have to do with Clinton’s departure from the administration in 2013. In another study, from 2014, the center noted that the official “language used to describe the rebalance has changed over time, particularly since the initial formulation of the rebalance.” That’s a natural consequence of the fact that Clinton, who provided the first definition for the rebalance, was no longer active in its implementation, and her successor has had other priorities.

Kerry’s attention to issues in the Middle East, from an aborted attempt to revive the Israel-Palestine peace process to the successful conclusion of a nuclear deal with Iran, contributed to perceptions that he was simply not as interested in the rebalance as Clinton had been. His itinerary suggests that there’s some truth to that claim. Whereas Clinton’s trips to Asia accounted for a quarter of her total travel, for Kerry, stops in the Asia-Pacific made up close to 15.6 percent of his travel through March — putting him behind not only Clinton but also Rice (at 17.5 percent).

Others say the U.S. is being outmaneuvered militarily in the region,particularly in the wake of budget-tightening after sequestration. With a rapidly evolving security environment in the Asia-Pacific (including China’s continued military buildup), critics argue that speed is crucial. And there’s no doubt that sequestration and budget cuts have hurt the Pentagon’s vision for the rebalance. As Pentagon spokesman John Kirby told reporters in 2014, “The defense strategy that we put forward, which allows us to conduct this rebalance … will be put in jeopardy” under continued sequestration.

Although Clinton had little say in the size or content of Pentagon budgets, the rebalance was envisioned as a comprehensive policy joining together diplomatic, military and economic engagement. When one leg is seen as lacking, the pivot strategy as a whole comes into question, reigniting lingering questions about American commitment to the region.

None of these criticisms questions the wisdom of the rebalance — on the contrary, detractors argue that it hasn’t gone far enough. Given the former secretary’s personal involvement in crafting and carrying out the rebalance, and the fundamental economic and security logic behind it, it’s hard to imagine a President Clinton turning her back on such a major U.S. foreign policy initiative. She herself has noted that the rebalance is a work in progress, as some in the region still have doubts about how the Asia-Pacific fits into U.S. foreign policy.

“I think we’ve come some ways in trying to rebalance,” Clinton said in September at Brookings, “but we have a long way to go, and there’s much at stake in how we deal with all the players in Asia.”