The rolling hills of Scotland’s southern lowlands are an unlikely venue for a flourishing Buddhist culture, and yet rows of multicolored Tibetan prayer flags – red, white, yellow, blue, and green – flutter in Eskdalemuir’s breeze, their prayers slowly fading as they become entwined with the elements. Indeed, the popularity of Tibetan culture in the West is a surprising phenomenon; especially considering that Tibet had little contact with the outside world until the twilight years of the 18th century. Its spread, much like the prayers on Tibetan flags, is an extraordinary story of cultural export.

The Samye Ling Stupa was consecrated on August 3, 2000 on Dharmachakra Day to mark the new millennium. It was the first stupa to be built in the United Kingdom and is dedicated to healing the environment and overcoming the obstacles to world peace. Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Scotland’s engagement with Buddhism emerged through its imperial networks across Asia, particularly the Theravada traditions of Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. This engagement culminated in the founding of the Pāli Text Society in 1881, which undertook the ambitious task of translating the Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhist texts into English. Pāli is the language in which the oldest scriptures of Theravada Buddhism was written. Engagement with Tibetan Buddhism occurred much later, following an ambitious espionage campaign by Captain Montgomerie to infiltrate the secretive Lhasa at the peak (literally) of the Great Game. His spies hid secretive materials inside Tibetan prayer wheels.

The “Mani Korlo” or Prayer Wheel House has 45 wheels containing millions of prayers. The wheels are run by electric motors and “transmit prayers day and night.” Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Following this, the growth of Scotland’s Buddhist community was slow but steady, culminating in the foundation of the Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan center in 1967. The monastery practices the Karma Kagyu school of thought – an offshoot of the Kagyu Tradition, one of the four major disciplines of Tibetan Buddhism – is believed to have been founded in the 10th century by Tilopo, a Buddhist yogi. Its main distinctions are its emphasis on orally imparting knowledge, and respect for lineage.

The Settlement Experiment

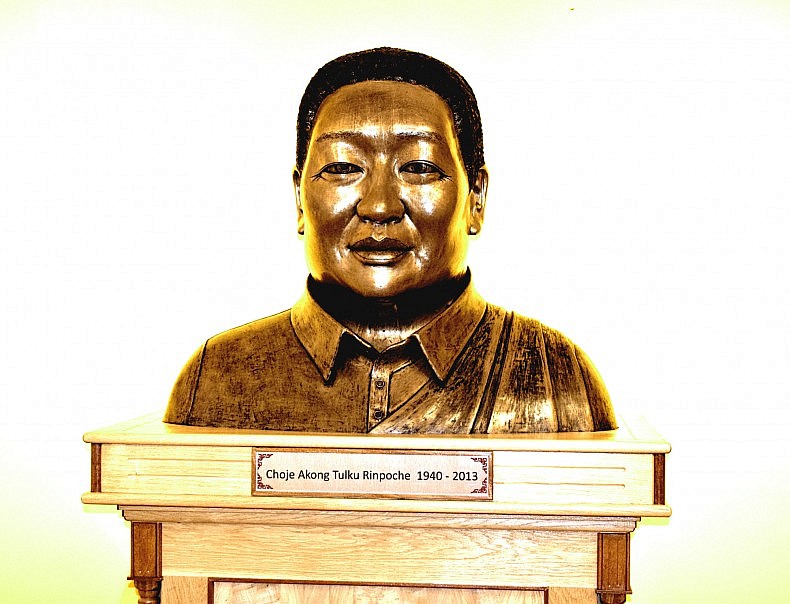

Samye Ling, meaning “the place beyond conception,” was the first monastery to be founded in the West. Its co-founder, Choje Akong Rinpoche, was recognized as an incarnate lama as a young child and became the abbot of the Dolma Lhakhang monastery. Following a failed Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule in 1959, Choje Akong fled to India by foot; a perilous journey of horrendous suffering, in which thousands of refugees starved to death, or simply died of exhaustion. Four years later, he was working as a hospital orderly in Oxford. His immense monastic prestige had rapidly unraveled, leaving him scrubbing toilets in a foreign land.

The hardship he experienced during these years had a profound impact on his world outlook. Importantly, Choje arrived in the UK during the emergence of the swinging 1960s, with its radical politics and counterculture movements, sparking widespread enthusiasm for Tibetan Buddhism. It’s within this context that Choje Akong Rinpoche and Trungpa Rinpoche took over a retreat center in the south of Scotland, which became Samye Ling in 1967.

A Bodh statue in Samye Ling. Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Choje Akong Rinpoche invited many prominent lamas to teach at the monastery. Students studied the Kagyu system of meditation there, with famous faces among their ranks such as Leonard Cohen and David Bowie. In fact, Bowie not only studied at Samye Ling; he almost became a monk there, stating in an interview that:

I was a terribly earnest Buddhist at the time […] I had stayed in their monastery and was going through their exams, and yet I had this feeling that it is not right for me. I suddenly realized how close it all was: another month and my head would have been shaved.

Local legend has it that monks at Samye Ling recognized something special in him as an artist, and encouraged him to leave the monastery and focus on his music.

The Samye Ling Community

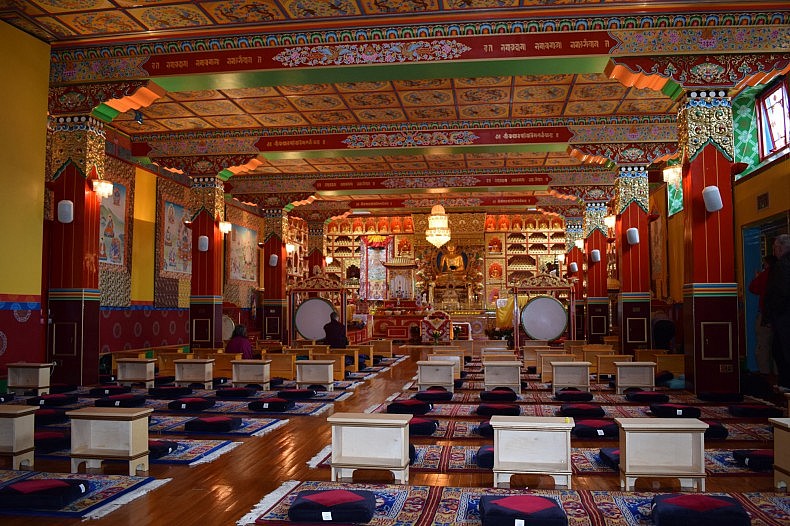

Anyone visiting Samye Ling can’t help but admire the sheer scale of the ambition it embodies. The voluntarism and grassroots community building by a refugee community are hard to match, and gives a sense of hope during the uncharitable debates surrounding Europe’s current refugee crisis. The temple is highly ornate, with paintings and statues scattered within its walls, with the ubiquitous chanting echoing across its hall: Om mani padme hum. The first word Om is a sacred syllable found in Indian religions. The word Mani means “jewel,” Padme means “lotus flower,” and Hum represents the spirit of enlightenment.

The monastery’s prayer room. Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Choje Akong Rinpoche was a traditionalist, and his driving motivation for building the community was the preservation of Tibetan Buddhism in the face of China’s obliteration of the region’s monasteries. Despite these stark problems, Choje maintained good relations with Beijing, frequently visiting his homeland. Furthermore, he was heavily involved in humanitarian work, setting up schools, clinics, and reforestation projects across India and Nepal.

As a symbolic gesture, Akong Rinpoche embraced both Scottish and Tibetan cultures in Samye Ling. The monastery has its own unique Tartan pattern recognised by Scotland’s official Tartan registry which is infused with the colours of Tibetan flags (blue, white, red, green and yellow – representing the five elements).

A “clootie tree,” originating from ancient Celtic traditions in which multicolored strips of cloth were dipped into spring wells and wrapped around trees as part of a healing ritual. Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Tragically, Choje Akong Rinpoche was murdered in China in 2013, along with his nephew, Loga, and assistant, Chime Wangyal. The assailant, Tudeng Gusha, claimed that the lama owed him 2.7 million yuan for sculpting projects. Documents signed by Tudeng contradict the claim, stating quite clearly the labor was conducted on a voluntary basis in exchange for food and accommodation. Tudeng was sentenced to death this February by the Chinese authorities. The monks of Samye Ling have voiced their concern against the verdict, stressing their opposition to killing, and instead call for forgiveness.

The monastery continues to thrive and recently opened an exhibition dedicated to the life and work of Akong Rinpoche.

Choje Akong Rinpoche (1940-2013), co-founder of Kagyu Samye Ling. Photo by Bradley Jardine.

Sakshi Rai is a postgraduate from the University of Glasgow specializing in Development Economics in South Asia. She is currently working as a researcher at Pragya in India.

Bradley Jardine is a regular contributor for The Diplomat.