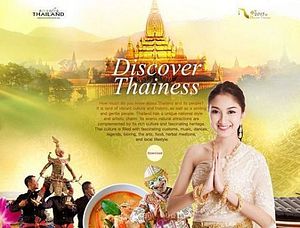

According to Thailand’s Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, this year’s theme for tourism is “Discover Thainess.” What does “Thainess” look like in a country of 67 million?

According to the Tourism Authority of Thailand’s (TAT) “Discover Thainess” website, it looks female: it is the graceful Thai woman clad in the sabai and phaasin who greets travelers on a gleaming sign in Suvarnabhumi airport, the gentle female Thai rice farmer, and the Thai maiden meditating peacefully. With the exception of Muay Thai, the online contests sponsored by TAT all feature demonstrations from swaying in Thai traditional dance to making Thai-style flower garlands. In a press release, the TAT proudly boasts that it “spotlights essential Thai culture.” The state’s essentialization of Thai identity is exotic, packaged for ready consumption, and undoubtedly feminine.

And this version of Thailand sells. Thirty million tourists visited Thailand this year, as the military continues to crack down on online criticism, enforce their own version of martial law and summon politicians, academics, and activists for attitude adjustments. The gendered identity of state-created “Thainess” is one that has allowed repression to continue without considerable international backlash, particularly with regards to Thailand’s most precious industry.

And this version of Thailand sells. Thirty million tourists visited Thailand this year, as the military continues to crack down on online criticism, enforce their own version of martial law and summon politicians, academics, and activists for attitude adjustments. The gendered identity of state-created “Thainess” is one that has allowed repression to continue without considerable international backlash, particularly with regards to Thailand’s most precious industry.

Prayuth masks his authoritarianism by hiding it behind the images of women’s bodies. These bodies are performing a “traditional” Thai culture owned by the state; these bodies are harmless embodiments of the Thai populace; and these bodies are controlled in their actions, in the way that Thai people are now expected to be with their thoughts. As Prayuth sells Thailand to Thai people through female objectification, it is easy to forget the human rights abuses of a military state. And this is part of a tradition that has allowed Thai citizens to remain complicit in condoning the parade of regimes in Thai history.

Female Objectification as Nation Building

Perhaps the only thing in Thailand consistent enough to be called “Thainess” is the strict policing of Thai culture through women’s bodies. All of Thailand’s military dictators, from Phibun in the 1930s to Suchinda in the ’90s, have variously used the image of Thai women to sell their brutally repressive regimes at home and abroad.

From the outset, the military chose to “civilize” women as the strategy for modernizing the nation. Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, known as Phibun, came to power in 1938, when Thailand’s neighboring Burma, Cambodia, and Laos were still under colonial rule. In his program of nation-building, it mattered that Thailand – especially Thai women – looked Western enough to convince the Western world that Thailand was not a nation to be colonized. The 1942 National Cultural Development Act set official standards for dress. Thai women were ordered to discard the pant-like chongkraben in favor of the skirt-like phaasin, and could be arrested for not wearing hats. Phibun’s version of Prayut’s “Discover Thainess” slogan was “The Thais are a well dressed nation.”

An official proclamation on “Thai Culture” by the government, on the left showing “What Must Not Be Done” and on the right, “What Must Be Done”.

According to Phibun, women were “Flowers of the Nation,” and had to be displayed as such. In seeking the widest audience for displaying the Western-clad women of Thai civilization, the state began sponsoring Thai beauty contests for “Miss Thailand.” This did two things. Firstly, it initiated a strategy of appropriating women’s bodies for the state’s agenda. Second, it created a state-sponsored ideal of a Thai woman that privileged the Bangkok-based elite who could afford Western dress. The elite claim that Thai women stand on equal footing with men today, but it is a claim that only speaks to their echelon.

In the 1950s and ’60s, dictators reanimated beauty contests, this time to sell the country to America as an anti-communist ally. Women became symbols of capitalism – they were commodities, their bodies and lives given monetary value, and put on display. Miss Thailand lapsed when Phibun’s dictatorship was forced to an end by his support of the Japanese in World War II, but beauty contests were brought back under Sarit in the ’50s and Thanom in the ’60s, who used the image of Thai women to distract the public from their repression. Beauty contests flourished as Sarit Thanarat’s junta tightened control over the political sphere, suspending political parties, elections, and the constitution. These female commodities were sold for the international perception of Thailand as a pro-capitalist nation.

Media: Creating Gendered National Identity

The introduction of electricity in rural Thailand brought Miss Thailand to televisions across the provinces, magnifying its importance as a shared national experience. Funded by American Cold War “Development Aid,” Sarit’s program of infrastructure development also meant that electronic media – especially television – was suddenly accessible everywhere. For Sarit’s authoritarian government, television was promoted less as an entertainment device than as a tool for state education and public relations. The “Miss Thailand Channel 4 Television Pageant” was immensely popular. Sarit averted the eyes of the nation from his illegitimate rule, training their eyes instead on the parading bodies of Thai women.

It also established the precedent for popular programming through female objectification. The media, sponsored by the government, created the national image of the beauty contests, but the huge audiences they commanded also shaped the media. As a show scripted for the male gaze, but whose audiences were also women, it created and legitimized the norm of displaying and policing female bodies. The demand for female bodies onscreen was readily met with a supply of advertisements and TV series that used “pretties” and beautiful movie stars to sell their products. Female beauty became public property.

To be clear, beauty contests also function as a pathway for socio-economic mobility for rural women. For those fortunate enough to be born with beauty (or who hire agents good enough to transform them), the empowerment and economic autonomy accorded to successful beauty queens is important. But when Thai femininity has been defined by and for Bangkok, they have to compete according to ideals of beauty set against them. The classism is clear: In the last 20 years, only four Miss Thailand winners came from outside of Bangkok.

Female Objectification and Foreign Relations

Through Miss Universe, female beauty became the face of Thai identity to the world.

When Thanom came to power in 1963, his search for a national symbol that would unite the country under his dictatorship came to an end with Apasara Hongsakun, who in 1964 became the first Thai to win Miss Universe. The outburst of national pride and international acclaim was a testament to the power of female beauty in eclipsing the massive corruption and anti-communist violence of the Thanom regime. In 1965, a TAT official said”

“By obtaining this title, Apasara made Thailand more famous. When American people know Thai people in this way, American policy oriented towards helping Thailand will tighten the friendship between the two countries.”

Suddenly, Miss Thailand became a part of foreign public-relations policy. Women’s bodies could be used to catapult Thailand to international fame without drawing attention to the authoritarianism of its government.

“Discover Thainess”

In the globalized era of neo-colonialism, Thailand is still selling itself to remain independent. Tourist campaigns in the past have always been marketed to a certain audience, from 1997’s “Amazing Thailand,” 2001’s “Be My Guest,” and 2004’s “Unseen Thailand.” But “Discover Thainess” is no longer about tourism – it is about much more.

We have entered the third age of policing Thai identity. Thainess is no longer westernized, nor completely sexualized, but it is the Thainess that best protects Prayuth’s state: traditional, harmless, and controlled. Amidst unfavorable international attention, the pressure for an identity that conforms to and vindicates the military’s narrative has risen. And this identity – as it has been since the beginning of Thai autocracy – is both exotic and traditional, mediated through the face and body of a woman.

Through female objectification, women are brought into the public sphere but only in ways that do not change patriarchal systems of power. Their visibility is unmatched when selling the nation, but their voices are unheard when deciding where the nation goes.

The feminine image works to mask the masculine, militarized nature of political power in Thailand. Few tourists know – or care – about the extent to which the military regime polices freedom of thought in Thailand. It is difficult to imagine rule by the force beneath the smiling image of a Thai woman with her hands clasped in a wai.

Jasmine Chia is a student at Harvard University.