High within a Himalayan valley, snow-capped peaks rising all around, the nation of Tibet is alive. Houses made from mud and wood crowd together in lines and in the paths that run between, Tibetan prayer flags blow in the wind. The phrase “tashi delek” echoes through the streets as neighbors passing each other clasp their hands together, bow their heads and exchange greetings in Tibetan. Many of them wear small photos of the Dalai Lama around their neck.

The Dalai Lama, the spiritual and political leader of Tibet, fled Chinese occupation in 1959 and set up a government-in-exile in Dharamsala, India. Hundreds of thousands of refugees followed, and with the help of the government-in-exile, created a network of Tibetan settlements throughout Nepal and India aimed at preserving their culture and identity. The Tserok camp, a remote Himalayan outpost in Nepal, offers a clear example of how deep the government-in-exile can reach and how resilient the nation has been.

Norbu Richoe, 70, was one of the first Tibetans to settle at Tserok.

After fleeing Tibet as a child, Richoe joined a guerrilla resistance group opposed to Chinese rule that was based just over the border in Nepal’s Mustang district. After 15 years of fighting, at the request of the Dalai Lama, the fighters laid down their arms.

The Tserok refugee camp, located within the Mustang district, is the closest to the border of Nepal’s 14 Tibetan camps. The first basic road up the valley was not completed until 2009, and even now the settlement is a hike across the Kali Gandaki River. To survive the long Himalayan winters supplies had to be carried in on a three-day trek by foot, “but many of us here had the same idea,” explains Richoe. “We wanted to remain close to Tibet even if it meant more struggle.”

Norbu Phuntsok, 60, is the head of the settlement. He was nominated for the post at a community meeting in 2008 and then appointed by the government-in-exile. Phuntsok is the main point of contact between Dharamsala and the 225 people who call Tserok home, though a representative from the Tibetan government also visits twice a year.

“Everyone here is proud to say they are Tibetan,” says Phuntsok. “And we may look happy, but inside we all know we must get back. It is everyone’s dream to return.”

The steadfast faith that they will one day return to a free Tibet is universal throughout Tserok, as is their faith in the leadership of the government-in-exile.

Each Tibetan refugee above six years old can apply for the Green Book, an identity document distributed by the government-in-exile. The document is not recognized by any other nation, but around Tserok residents proudly display them in their homes. Adults are expected to pay a small, voluntary tax each year and it is recorded in their Green Book. Non-Tibetans who want to show support are given a Blue Book and also contribute to the exiled government’s coffers.

That money, plus support from a variety of different governments and NGOs, comes back to Tserok to help preserve Tibetan traditions. “The school was built in 1989,” explains Dakpa Richoe, 43, headmaster of Tserok school. Richoe himself is a product of the Tibetan school system. His parents died when he was five years old and he was raised in a dormitory and school for Tibetan orphans.

The five teachers in Tserok, all born and raised in the settlement, are paid the equivalent of about $180 a month each with funds from Dharamsala.

The government-in-exile has composed a national anthem to help foster patriotism and it is sung each day in the school. They have also created Tibetan Uprising Day, a holiday celebrated each March throughout the school system and in every settlement.

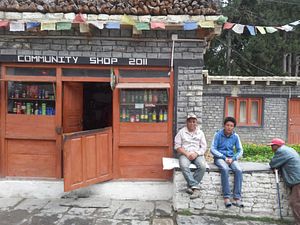

Tserok residents mostly work in agriculture and while some may also sell handicrafts or work within the tourism industry the settlement strives for self-sufficiency. There is a community hall, monastery, health clinic, four-room hotel, and restaurant as well as a general store.

The store and hotel are collectively managed, with residents on rotating working shifts. At night it turns into a community space where people come to chat with friends. The profits are put into a general fund which acts as community insurance that can be used if someone becomes very sick or has an accident.

For larger accidents the community can call upon the Tibetan government. “In 2014 the roof of the community center collapsed under heavy snow,” explained Phuntsok. “I called up Dharamsala and told them what happened. They asked how much it would cost to repair and sent funds the very next day.”

Nepali police leave the settlement to fend for itself most of the time and an eight-person team elected by the community settles disputes and handles security. “If we can’t find a solution to a conflict we can send the parties to Kathmandu which has a higher court, or even to Dharamsala,” explains Tsering Wangdu, 33, one of the members, “though we’ve never had to do that.”

Wangdu also grows apple trees and rents a souvenir shop in Jomson, the district capital and a two-hour hike away. “We can’t own any property [because we are refugees] so we have to rent everything,” Wangdu explains.

One hundred forty-seven nations have signed the United Nations Convention Relating to Refugee Status, which guarantees their refugee populations certain rights. Nepal is not one of them. Though most of the 20,000 Tibetans in Nepal today were born here, they do not have citizenship and are officially stateless. Besides not being allowed to own property, this also makes obtaining any document—from a driving license to a work permit or a travel visa—extremely difficult by legal means.

The Nepali Home Ministry has recognized the problem and, since 2010, has been working toward a national ID card which may include non-citizens. The much delayed program is still “twelve months from being ready to launch,” according to Ram Thapa, the ID engineer with the National ID Card Management Center. Even then, the first phase of the program will only cover Nepali citizens; non-citizens may be covered two years later.

The ID program could give Tibetans many of the rights they are denied today but the real dream is not an easier life in Nepal, it is a return to to their homeland.

Norbu Richoe, the 70 year-old former guerrilla fighter, has not given up his dream. “Tibet will be free again,” he says. “But until then, wherever we are together, we will keep the nation alive.”

John Dennehy has written about the developing world and migration for places such as The Guardian, Vice and Narrative. He is currently based in Nepal.