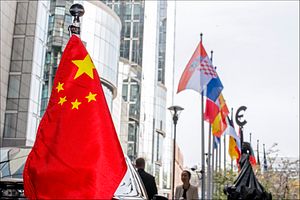

On July 12-13, 2016, the annual EU-China Summit will take place in Beijing. After two weeks of Brexit-induced European turmoil, China is likely to see this as an opportunity to take advantage of the EU’s member states for better trade deals.

But while China might think Europe is weak right now, it is vital that the EU does not water down its commitment to human rights and democracy to appease the Chinese government. In fact, without the UK, the EU may be in a stronger position to emphasize the importance of human rights and the rule of law.

The UK was one of China’s biggest apologists within the EU as they promoted a so-called “golden era” of friendship. Without the UK, the EU can be more principled and use this Summit to send a clear message that while it’s open to greater trade with China, European support for human rights in the country is non-negotiable. Specifically, EU leaders need to strongly affirm that support for Chinese human rights defenders (HRDs) will continue despite the Chinese government’s attempts to silence them.

At the conclusion of the last EU-China Summit in June 2015, both sides issued a statement agreeing to “enhance exchanges on human rights… on the basis on equality and mutual respect, and confirmed their readiness to cooperate under the UN human rights mechanisms.” Since then, the most systematic and wide ranging crackdown on HRDs in decades has taken place in China. Agreements on human rights with the EU mean very little to Chinese authorities, who launched a devastating attack on the human rights community just ten days after the Summit ended. Hundreds of lawyers, human rights defenders, and their families were detained, harassed, intimidated, and interrogated. At least 24 HRDs remain in detention from that crackdown; they join the scores of other defenders languishing in police custody and prison as a result of their activism. Of those 24, five are being held on charges of “inciting subversion of state power” and 11 on the more serious charge of “subversion of state power.”

The EU’s new China strategy paper, released on June 22, emphasizes Europe’s promotion of universal values in its relationship with China, but provides no substantive detail about how it will do so. The EU cannot continue to segregate human rights reform from its diplomatic and trade relationships with China – largely ignoring the former while marching ahead on the latter. Despite the EU’s promise to “hold China to account for its human rights record,” as it stands, the Chinese authorities have not been made to account for much.

In the past year, at least five HRDs have been grabbed from third countries and forcibly repatriated in contravention of international law. HRDs in prison and suffering from illnesses have been denied adequate medical attention. HRDs in detention have been tortured. At least 39 HRDs have been banned from leaving the country because of their activism. Family members of HRDs have been specifically targeted – they have been detained, placed under house arrest, fired from their jobs, or harassed on the street. Lawyers appointed by family members for detained HRDs have been dismissed by the authorities and have sometimes themselves been threatened with prosecution for simply attempting to fulfill their legal responsibilities. Very lengthy prison sentences for activism have once again been introduced. In January, a man in Xinjiang province was sentenced to 19 years in prison for posting essays online critical of the Chinese Communist Party while just two weeks ago two veteran democracy activists were sentenced to 11 and 10.5 years’ imprisonment for publishing essays promoting human rights and democracy on overseas websites.

The argument that demanding human rights reform from a trade partner comes at the expense of financial gain is premised on a false dichotomy. Human rights and trade are not an either-or choice that the EU must make. A stable economic and trade relationship risks being undermined by the lurch to repression and the arbitrary abuse of legal process. The EU can instead use trade deals to leverage reform that Chinese human rights defenders are fighting for inside the country. In the EU’s China strategy paper, it is clearly stated that “China needs the EU as much as the EU needs China” and “China’s needs are as great as ours and failure to cooperate also brings adverse consequences for China”.

If the EU is genuine in upholding human rights and rule of law as intrinsic values, it needs to find a new approach to its relationship with China, beginning at this EU-China Summit. Respect for human rights and the work of human rights defenders need to be at the heart of all its negotiations with China, making clear that the relationship can only develop if certain rights standards are met. Otherwise, the EU risks a race to the bottom as an increasingly authoritarian Xi Jinping tries to strangle the life out of civil society in China. As the U.K. exits stage left, the debate around European values is being re-ignited, giving the EU an opportunity to assert those values on the global stage and show the world that the union can be a strong, confident political entity without the U.K.

Andrew Anderson is the Deputy Director of Front Line Defenders in Dublin.