In 2007, a Pakistani schoolteacher was arrested and put on trial by the Taliban on charges of preserving the “symbols of infidelity.”

It was a sheer stroke of luck that the Taliban’s ruthless justice department could not find enough proof. The teacher is still alive and struggling to preserve the 2,000 year old Buddhist history in Swat, the picturesque valley in northern Pakistan where a Taliban assassin targeted the Nobel Laureate Malala Yousafzai in October 2010.

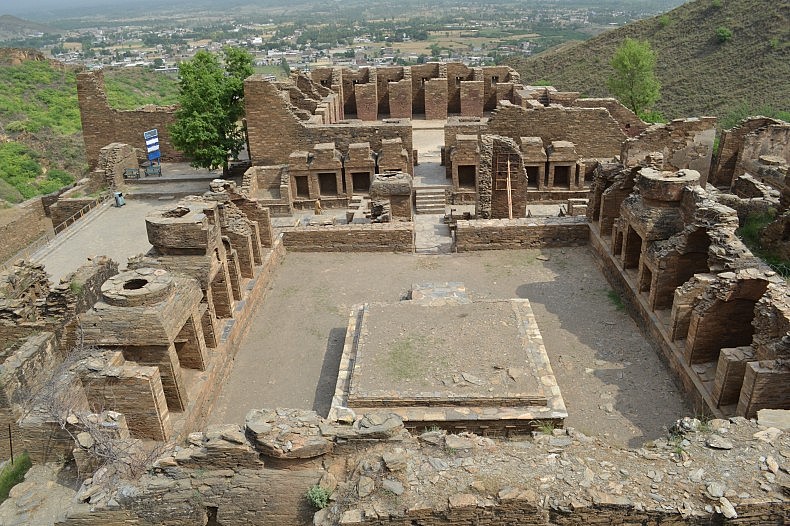

Osman Ulasyar, 45, was arrested at his school, blindfolded and packed in a car to face Taliban justice. His crime: Stopping local boys from playing cricket in the middle of the Buddhist Stupa Court, which dates back to the 1st century CE.

“The armed Taliban has been routed from Swat and the threat is over now. But these sites face new threats from land mafia; artifact smugglers; negligence of the government; and lack of awareness among people about its history,” says Osman, who recently constructed a 300-feet protective wall to safeguard the stupa court. He had to sell his car to pay for the construction costs.

Osman’s ordeal is in fact the tale of the vanishing historical sites dating back to the glorious period of the Gandhara civilization in today’s northern Pakistan. Once the symbol of religious harmony, the region is now known for religious intolerance and Taliban extremism.

The Swat Valley, where Osman lives, was seized by armed members of the Tehreek-e-Taliban-e-Pakistan, led by cleric Mullah Fazlullah, in 2008 and 2009. Fazlullah has now been elevated to the rank of the TTP’s top boss. Pakistani officials believe Fazlullah is hiding somewhere on the Afghan side of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

In December 2014, Fazlullah masterminded an attack on a military-run school in the city of Peshawar, killing 150 people, mostly schoolchildren. The attack was the deadliest in Pakistan’s history of terrorist attacks.

Back when Osman was presented before a Taliban judge, the judge accused him of committing heresy by securing the Buddhist sites, which the Taliban call the “symbols of infidelity.” Mullah Fazlullah’s armed brigades had forcefully banned listening to music, watching television, women coming to the markets, and girls attending schools in Swat Valley.

Before going after Osman, the Taliban in Swat dynamited a Buddhist carving in Jehan Abad. The Buddha statue in Jehan Abad was the largest such rock carving in the world after the statues of Bamiyan, says Osman. The Bamiyan statues were bombed by the Afghan Taliban in late 2001.

“Gandhara was the center of religious harmony,” says Dr. Abdul Samad, director of archaeology and museums in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. “The basic concept of religious harmony that we see in the modern day world flourished here 2000 years ago. It was here that one finds Greek, Roman, Persian, Hindu, and Buddhist gods in a single panel in Peshawar Museum,” Samad explains.

However, while Samad and people like him understand the concept of religious harmony and the importance of historical heritage, the vast majority in Muslim Pakistan, a country that was created 69 years ago, have no interest in exploring beyond the arrival of Arab armies in the Indian sub-continent in 712 CE, which marked the start of Muslim period in this region.

Pakistan came into existence in 1947 after the division of British India into two independent states, India and Pakistan. For centuries, Muslim and Hindus co-existed in India, despite differences in their religious beliefs and ideals. However, the main reason mentioned for the separation was that Muslims need a separate homeland to independently practice their faith and belief. This was later named as the “two-nation theory” in the national narrative of the newly-emerged Pakistan.

However, Muslim Pakistan, separated from “Hindu India,” received the first blow when the Muslims of Bengal, then known as East Pakistan, announced a separate independent country in the name of Bangladesh in 1971. The reason for the Bangladeshis separation from their co-religionists was based on ethnic differences and economic disparities.

Since then, present day Pakistan has been struggling to keep its diverse ethnicities, including Punjabis, Sindhis, Balochis, Pashtuns, and Seraikis united by using the religion of Islam as a glue. To help highlight the Islamic character of the otherwise diverse Pakistani society, the period of pre-Islamic history was replaced with the arrival of Islam in the 8th century CE in history lessons.

After 1971, Pakistan’s “students were deprived of learning about pre-Islamic history of their region. Instead, history books now started with the Arab conquest of Sindh and swiftly jumped to the Muslim conquerors from Central Asia,” writes columnist Nadeem F. Paracha in Pakistan’s Dawn.

I visited the Takht Bhai ruins, one of the eight sites in Pakistan with UNESCO World Heritage status, in May 2016. Standing at the serene monastery complex on a hilltop overlooking the bustling town of Takht Bhai, I asked several visitors from different age groups about the history of the site. I was amazed to hear their answers. A few said the ruins were from the British cantonment; others said these are the remnants of infidels destroyed by the wrath of God. Many say they were picnickers and not interested in who lived here and when.

A few kilometers from Takht Bhai is another UNESCO World Heritage Site: the town of Sri Behlol, located on a hillock and surrounded by an approximately 3000 year old wall. People have constructed houses on the land and the area is notorious for illicit excavations without being taken notice by the government.

During a visit to the town, I found houses constructed on the foundation of the historical wall, the only standing memory in this World Heritage Site now. In several places, the villagers had picked out stones from the wall to construct their own houses. Parts of the wall are buried under heaps of garbage thrown from the houses built over the wall.

“When I was a child, our grandfathers used to dig for idols (statues) in the fields and sell it to people coming from the urban centers. I have seen carts full of old things such as idols, broken pieces of cooking pots, human bones purchased by city traders from the villagers,” said 50-year-old Lal Mir, who lives in Sri Behlol and owns a house on the historical site. “Smugglers,” rather than “traders,” may be a more apt term.

Mir said his parents and grandparents told him that the people who lived here were drowned during the Noah floods, the biblical tale also mentioned in the Quran, the Muslim holy book. The Noah flood is a story often repeated by imams in Pakistan during Friday sermons to instill the fear of God among the people.

Most of the villagers in Sri Behlol are confident that they are earning money as well as Sawab (blessings of God) by digging out the “remnants of infidels” and selling it in the market. They are, in fact, performing a religious duty, they believe.

The areas around Takht Bhai and Sri Behlol, located some 70 kilometers northwest of the city of Peshawar, are so rich with historical sites that people used to recover statues, relics, and potteries whenever they dug into the land to construct houses. One such scene was the site of a mosque in the nearby village of Kot in the same locality.

Human skulls, bones, potteries, and statues were recovered when villagers in Kot dug to construct a mosque, said a local man, Javid Khan. Khan accompanied me to the mosque’s construction site on May 3, 2016. However, as soon as we had fixed our cameras to record the scene, angry bearded men surrounded us.

“This is desecration of our holy mosque. Take your propaganda machines out of here, else we will throw you out,” said one angry young man. We had to wrap up. Later, some villagers from the same neighborhood privately told me that the items recovered from the building site were secretly sold to artifacts smugglers.

In March 2016, the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations announced the confiscation of a “second century bodhisattva schist head” from the Gandhara civilization. According to the New York Times, this was second time in matter of days that the federal agents seized what they described as illicit antiquities.

In recent years, as part of the devolution of power, Pakistan’s federal government has transferred authority of several erstwhile federal subjects to the provincial governments. The Department of Archaeology and Museums also came under the control of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial government.

Mahmood Khan, the minister in charge for archaeological sites and tourism in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, told me during a meeting on May 4, 2016 that his party government had introduced the Antiquity Bill in the provincial legislature to punish people for stealing and smuggling of artifacts or damaging the historical sites.

However, he added that the provincial government has to focus on many other important issues as well. “Archaeological sites are important, but we are facing many other key issues. We have some more important works on our to-do list including creation of jobs, alleviation of poverty, and addressing the issues of security and lawlessness,” he added.

Historically, the land of Gandhara has been well known since the reign of Cyrus the Great (558 – 528 BCE). The region consisted of the present day Peshawar and Swat Valleys in northern Pakistan and parts of Afghanistan. Some of the well-known dynasties that ruled Gandhara included Greeks, Mauryans, Scathians, Parthians, Kushans, and White Huns.

Dr. Luca Maria Oliveri, head of the Italian Archaeologist Mission in Pakistan, says this region has many riches of antiquity and the authorities need to bring all the historical sites under their supervision. Luca has been working in the country’s Swat Valley for the past 30 years.

When I visited Swat on May 7, I met Luca at the town of Borikot, where he was busy excavating the city of Bazeera from the time of Alexander the Great. “This is the city which became an Indo-Greek outpost and it is located at the place where Alexander fought one of his great battles in 327 BCE,” Luca said. The city of Bazeera, he explained, was abandoned in the concluding part of the 3rd century CE, at the end of the Kushan Empire.

Luca suggested that the government of Pakistan should expand the acquisition of archaeological sites to provide better management and proper protection.

According to Samad, head of the Archaeology Department, there are 6,000 historical sites in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Of those, 2,000 sites belong to the Gandhara Civilization. Of the 2,000 sites, several have been disappeared while many others, such as Sri Behlol, have forcefully been occupied by locals.

In Swat, Osman says, there were 21 “protected sites” registered with the archaeology and museum department; “five of those sites do not exist at all now.” Under the antiquity laws, no construction is allowed within 200 feet distance of the historical sites. However, in Swat, Osman showed us houses constructed less than 20 feet away from the stupa courts.

Recently, local officials proudly changed the name of one such historical site in Swat from Buth Kada (a place of statues/idols) to Gul Kada (place of flowers). When I asked the reason, Osman said with a sarcastic smile, “We Pakistanis are in the practice of Islamizing everything.”

Daud Khattak is Senior Editor for Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty’s Pashto language Mashaal Radio. Before joining RFERL, Khattak worked for The News International and London’s Sunday Times in Peshawar, Pakistan. He has also worked for Pajhwok Afghan News in Kabul.