Throughout history, the South China Sea has been a key passage of the Maritime Silk Road. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, proposed by China in 2013, is no exception. The past 20 years of history show us a basic truth: East Asian cooperation sails far in times of calm in the South China Sea, and stagnates in the shadows of uncertainty in this region.

The South China Sea issue currently is causing a series of negative effects on the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR). However, these effects have their limits; the negative impacts are short-term, localized, manageable, and will not radically hinder China and ASEAN from building OBOR. On the contrary, OBOR will provide a new momentum for peace in the South China Sea, and will continue promoting peace and stability in the region.

The Maritime Silk Road: From History to Reality

The “Maritime Silk Road”is a sea channel that starts from China’s southeastern ports, passes through the South China Sea and the Strait of Malacca, enters the Indian Ocean, and eventually reaches the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. The route links East Asia with the Middle East, East Africa, and Europe.

The Maritime Silk Road can be dated back to the ancient Chinese Qin and Han Dynasties. During the Han Dynasty, silk and southern Chinese porcelain were transported via this route to the Malay Peninsula and Sri Lanka. Southeast Asian perfume and dyes also reached China through these sea routes. The Maritime Silk Road matured during the Tang Dynasty, especially when, according to historical records, there was emigration and migration between Tang China and Southeast Asia. The Chinese and indigenous people in Southeast Asia jointly gave rise to early development in the region.

During the Song Dynasty, the Maritime Silk Road reached its heyday; Quanzhou and Guangzhou in China became international ports. The famous “Nanhai One” shipwreck is a symbol of the prosperity of the Song Silk Road. The voyages of Zheng He in the Ming Dynasty represented the peak of the Maritime Silk Road and extended the passage to the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Ancient China thus interacted with many ancient civilizations, ranging from those in Southeast Asia to East Africa. In addition to the intergovernmental “tribute trade,” there were also frequent civil personnel and cultural exchanges. In the end, a trade circle formed in ancient East and Southeast Asia, in which the South China Sea played a vital role.

In recent centuries, however, Asian countries have gone through a long and struggling process of national independence and state building. The tradition of the Maritime Silk Road has thus been overshadowed by the colonization and warfare brought by Western countries.

But times have changed. Since the 1980s, East Asia has once again become a model of economic growth for the world. Even while enjoying domestic economic growth, East Asian countries were heading toward economic integration as well. East Asia’s most dynamic regional integration organization — the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) — and the largest economy in East Asia — China — formed close trade relations and established a number of economic integration mechanisms including the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area.

As a new development approach for economic cooperation, in October 2013 during his visit to Indonesia, Chinese President Xi Jinping introduced the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” concept, which (along with the Silk Road Economic Belt) constitutes the OBOR initiative. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and the 2014 establishment of the “Mekong-Lancang Mechanism” laid out the basic framework of OBOR between China and ASEAN.

Only two years after the initiation of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and Mekong-Lancang Mechanism, related governments have given positive responses. The 2015 “People’s Republic of China and ASEAN on the revision of ‘China-ASEAN Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement’ and Protocols under the Part of the Agreement,” the 2016 “Joint Declaration of Implementation Plan of China-ASEAN Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity,” and the “Joint Statement of Mekong-Lancang Countries Energy Cooperation” are the latest results of China and ASEAN jointly building OBOR.

The South China Sea and the East Asian Regional Economic Integration

While East Asian countries focus on developing their domestic economies and promoting regional economic integration, the specter of security problems loom on the South China Sea. As the most important geopolitical issue in the China-ASEAN relationship, developments in the South China Sea will have a crucial impact on regional economic integration.

From the 1990s to the first decade of the 21st century, the “security dividend” produced by peace and stability in the South China Sea greatly promoted the development of East Asian integration. In the early 1990s, China improved and built diplomatic relations with ASEAN countries; during the late 1990s China also won the trust of ASEAN with the support Beijing gave ASEAN countries during the 1997 financial crisis.

In 2002, China and relevant countries signed the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.” The declaration identified the dispute resolution recognized by all parties, shaped the behavior of the parties, and maintained the stability of the South China Sea to some extent.

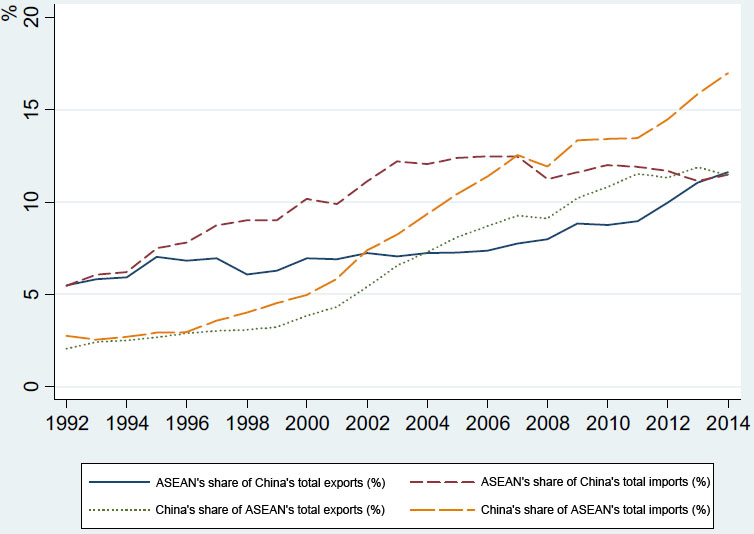

Under the premise of political stability in the South China Sea, economic and trade cooperation between China and ASEAN were leading the trend of East Asian integration. In trade, economic ties warm as political ties warm. China and ASEAN have led a double-digit growth rate in exports and imports over a long period. Bilateral trade dependence has gradually increased as well.

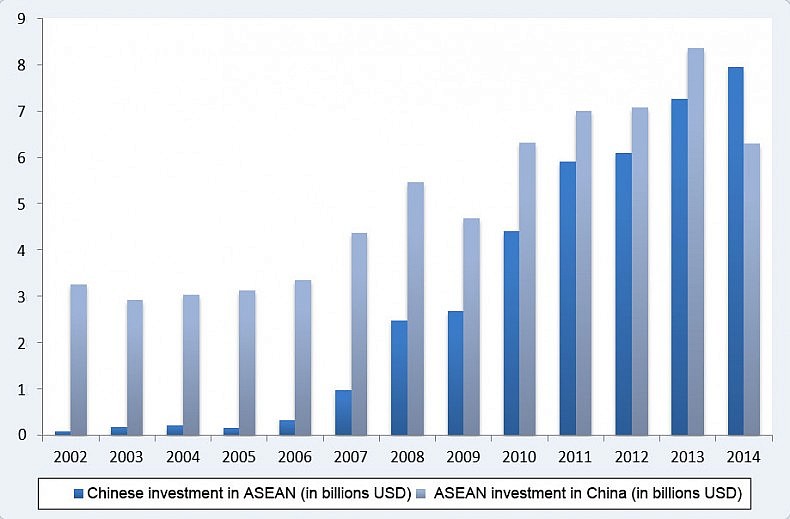

When it comes to investment flows, China-ASEAN direct investment increased consistently, thanks to the policy and regulation coordination made possible by stable bilateral relations between China and the ASEAN countries.

In the financial and macroeconomic sectors, as the economic partner who made a major contribution to fighting the Asian financial crisis in Southeast Asia, China long ago won a role in East Asian financial and monetary cooperation. China, Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN established the Chiang Mai Initiative in 2000. The initiative developed cooperation in four areas including detecting the flow of capital, monitoring the regional economy, establishing a bilateral currency swap network, and personnel training. Among those, the bilateral currency swap network is the most important.

After the 2008 global financial crisis, the initiative was further upgraded to the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization Agreement in 2010. The same group of countries also established the ASEAN Plus Three Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) in 2011, with Wei Benhua from China as its founding director. The fact that East Asian countries stood in solidarity facing world financial risks was also established on the basis of regional peace and stability.

However, after 2009 the United States’ Asia-Pacific rebalancing strategy brought security issues back into the Asia-Pacific by strengthening the role of the Asia-Pacific in its political, economic, and military discussions. The United States increased forward military deployment in the Asia-Pacific, deepened its Asia-Pacific alliance network, and expanded its involvement in hotspot issues. On the South China Sea issue, the United States chose to take the side of the Philippines in the 2012 Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island) incident to promote “internationalization” of South China Sea disputes. The U.S. Navy and Air Force frequently enter the South China Sea declaring “freedom of navigation,” and held military drills with allies. Economically, the United States added the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) to its Asian pivot strategy and led the negotiations. The agreement officially signed in early 2016 included five East and Southeast Asian countries (Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam).

Since 2009, East Asian security issues have been gradually warming up. Security now has a strong tendency to become the main topic of discussion at regional meetings, and has thus created resistance to the East Asian integration process. For example, China-ASEAN total trade dropped from around 40 percent year-on-year growth in 2010 to zero growth in 2015. Although there are many factors behind the decline, the interference of security issues is the most paramount. The re-emergence of security issues and regional system competition caused the economic integration process to suffer negative consequences.

China promoting regional integration created peace and stability in the South China Sea; the United States becoming involved in the security situation in the South China Sea only led to tensions in the region.

Of course, the East Asian integration process did not halt after 2009; it is still overcoming resistance to make some progress. Especially since China put forward OBOR in 2013, China and ASEAN’s integration process has regained momentum. China ASEAN completed an upgrade to their Free Trade Area in November 2015. Negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) are expected to close this year or next year; the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank launched by China was established; and China’s OBOR initiative is on the rise.

The Negative Impact of the South China Sea Issue on OBOR

China’s “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” initiative has received positive responses from ASEAN countries and achieved initial results in only three years. However, the rise of the South China Sea issue in recent years has become an obstacle to this process. If the South China Sea issue affects policy communication between China and ASEAN countries, it would likewise interfere with OBOR.

On the bilateral level, the Philippines strengthened security cooperation with the United States while focusing on national elections held this year. Vietnam and its former enemy the United States (which only recently ended its arm embargo on Hanoi) are evidently more interested in security issues than economic issues. In multilateral forums, the South China Sea has become more and more “of ASEAN”—a subject of discussion under the ASEAN mechanism. To some extent, the South China Sea issue has indeed weakened the mutual trust between China and some ASEAN countries in politics and security, especially those that have sovereignty and maritime delimitation disputes with China. It increases the difficulty of policy coordination to advance OBOR for China and relevant countries.

Geographically, OBOR’s development in Southeast Asia is not balanced, a problem that is related to the South China Sea issue. Although the Philippines is a target country for the initiative, it is undeniable that in recent years China has not achieved any policy agreements with the Philippines on intercommunication or interconnection. In contrast, China has advanced cooperation with other Southeast Asian countries, including signing infrastructure cooperation agreements with countries such as Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. The Mekong-Lancang Mechanism along Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia (none of which are claimants in the South China Sea) welcomes countries to have security and economic cooperation with China. In March 2016 China and countries along the Mekong-Lancang River signed agreements for energy capacity cooperation.

The intensification of the South China Sea issue, coupled with the recent global economic downturn and other factors, might have contributed to the declining growth rate of trade between China and ASEAN. In fact, since June 2015 when the situation began to heat up in the South China Sea, China’s import and exports to ASEAN have dropped sharply. When it comes to direct investment, while the annual amount of China-ASEAN two-way investment has grown, the growth rate has been declining. At the same time, Japan has exceeded China in investment in ASEAN for three consecutive years and also plans to increase the proportion of investment in infrastructure construction.

On a social level, the South China Sea issue may be colored with the “China threat theory” to hinder the implementation of OBOR. Some ASEAN countries have long-standing suspicions toward China and the Chinese people. With perceptions shaped through influential media reports from the West and ASEAN, Chinese behavior in maintaining its sovereignty in the South China Sea is likely to once again provoke nationalism and an anti-Chinese mentality in ASEAN nations. People-to-people communication, an important part of OBOR, may be affected by this trend. This impact of such a mentality is difficult to assess.

More evidence could be found by examining the progress elsewhere on the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. Looking to South Asia, the construction of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port, Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, Bangladesh’s Chittagong port, and so on, all of which bypass the South China Sea issue, have achieved much quicker progress. In Southeast Asia, cooperation with Indonesia is advancing relatively rapidly, but occasionally suffers political setbacks. Overall, progress in South Asia is faster than that in Southeast Asia; needless to say, the South China Sea issue has has some impact.

In short, if the South China Sea issue is not handled properly, there will be negative spillover, thereby undermining the basis of regional economic cooperation, and eventually leading to a “lose-lose” situation.

The South China Sea Issue Will Not Radically Hinder OBOR

Although the South China Sea issue may have some negative effects on OBOR, these impacts are limited and manageable, and ultimately will not radically hinder the initiative.

First, the South China Sea dispute is an issue of a temporary nature. Though tensions may seem to rise, the possibility of an armed conflict in the region remains relatively low. The U.S. military and political elites understand perfectly well the risk of military intervention in the political realm, and thus are not willing to spark military conflict with China. In fact, both the military budget and presidential election campaign are affecting U.S. military activities in the region, but the South China Sea should not be an area for Sino-American confrontation. That means tensions are likely to fall again from their current peak.

Moreover, tensions in the South China Sea are manageable. While the temporary nature of the South China Sea issue may not guarantee an ultimate solution to solve the dispute, the issue itself is nevertheless relatively stable in the sense that none of the parties concerned can easily change the structure of the problem. Given this, the concerned parties would either tend to extend the dimensions of the issue by strengthening communication and dialogue to avoid conflict (such as holding think tank dialogues and routine joint exercises), or develop new connections by expanding economic and trade cooperation for mutual benefit, and backing peaceful solutions to the South China Sea issue.

Furthermore, tensions in the South China Sea are localized. Focusing on territorial disputes and geopolitical issues in the South China Sea would only lead to a “zero sum game.” Meanwhile, economic cooperation under the framework of an institutional design of regional integration could best serve the interest of all parties — a “positive sum game.” Nevertheless, if the negative spillover effects of security issues come to undermine the basis of economic and trade cooperation in the region, ASEAN would obviously be the first to be affected. The China-proposed OBOR initiative shows the exactly right solution to all the problems above.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi considers ASEAN as the priority cooperation partner in the following four areas: the priority area for the construction of OBOR, which includes the construction of the China-Laos railway, China-Thailand railway and Jakarta-Bandung high speed railway in Indonesia.; the priority cooperation partner for free trade agreements, as the both sides have agreed to upgrade the China-ASEAN FTA to boost greater trade and investment ties, while RCEP is being negotiated; the priority partner for regional cooperation, including the Lancang-Mekong sub-regional development; and the priority partner for maritime cooperation, including maritime security cooperation and marine environmental cooperation. All these indicate that cooperation is still the mainstream in the region and provides an alternative approach to ease the tensions.

Based on the analysis above, we have every reason to believe that the South China Sea issue should not and will not radically hinder the progress of OBOR in Southeast Asia. On the contrary, the initiaitve will fundamentally promote peace and stability in the region.

OBOR: New Momentum for Peace and Stability

As stated earlier, the growing tensions in the South China Sea come at a time of economic integration in East Asia and amid the promotion of the China-proposed OBOR initiative, which requires a calm and stable regional environment. In turn, however, the construction of OBOR provides new momentum for peace and stability in the South China Sea.

Although the Philippines has been pushing for the South China Sea issue to become a problem in China-ASEAN relations, we should recognize and respect the fact that the issue itself is not a problem between ASEAN and China. As a result, the so-called international arbitration case initiated by the Philippines against China over the South China Sea would never get full support from ASEAN.

While the South China Sea issue involves individual countries, OBOR is for ASEAN as a whole. The ASEAN member states have benefited greatly from economic and trade exchanges with China; the updated China-ASEAN FTA is proof. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, though at an initial stage, is shaping a more diversified FTA, and a more flexible and open win-win vision, where all ASEAN countries can obtain investments that they urgently need, including manufacturing, infrastructure, and financial investments.

China and ASEAN countries should take a long-term perspective on the relationship between regional security and economic development. Therefore, the South China Sea issue should not be more than a short-term drag for all parties. Jointly building OBOR will provide opportunities for long-term economic development in the region.

The OBOR initiative is a regional economic cooperation mechanism with strong compatibility and feasibility. It is more inclusive than the U.S.-dominated TPP; while the latter focuses more on the so-called “standard clauses,” OBOR is able to adapt to changes through policy communication and coordination.

In this regard, it is now high time for China and the United States to hold substantive strategic dialogues. The China-proposed OBOR initiative does not necessarily mean competition or even conflict with the U.S.-dominated TPP. China is willing to cooperate with the United States and ASEAN countries to achieve mutual benefit and win-win results by means of strategic and economic dialogues.

China’s foreign trade is highly dependent on the shipping lanes of the South China Sea, and ASEAN countries are China’s important trade partners. To some extent, then, China is the main victim in the dispute. China should continue promoting the construction of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, while carefully handling the relationship between trade and economic policy and the tensions in the South China Sea. Economic and trade cooperation can become the anchor and propeller of China-ASEAN relations, and fundamentally promote long-term peace and stability in the South China Sea.

Wang Wen is the Executive Dean of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China (RDCY); Chen Xiaochen is a researcher at RDCY; Chang Yudi is an intern researcher at RDCY. Wang Wen and Chen Xiaochen both participated in the U.S.-China dialogue on the South China Sea held at the Carnegie Endowment in Washington D.C. on July 5, where a version of this paper was presented.