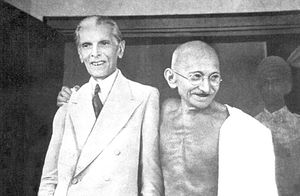

On August 14, Pakistan marked its 69th year of independence. Though there was much to celebrate of historical significance, the years since independence have brought Pakistanis little to celebrate. Instead there has been much soul searching, with a feeling of lost focus and purpose. The country finds itself gripped by a militant insurgency that has claimed the lives of thousands, with politicians too scared to speak against blasphemy laws that persecute minorities for fear of their lives and widespread sectarian killings, too name just a few of the issues Pakistan has to contend with. Rewind the clock 69 years and you find that Pakistan has become the polar opposite of the country envisaged by its founding father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Where did it all go so wrong?

“You are free. You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques, or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan”: On August 11, 1947, in unequivocal terms, Jinnah set out the foundations of Pakistan, which was to be a secular and liberal democracy guaranteeing freedom of religion. This speech provided the clearest indication of what shape Jinnah wanted his country to take. In the same speech he went further and claimed that “you may belong to any religion, caste or creed, that has nothing to do with the business of the state.” Yet Jinnah’s death, only a year after the birth of Pakistan, meant that he had no time to implement his vision for the new country.

After Jinnah’s death, with no national leader holding the country together, and with a threadbare state, a void opened up in Pakistan. This void has been filled by both civilian and military rulers who, in the absence of a national identity, have advanced their own competing visions of the state ever since. Religious groups along with civilian and military governments have sought to repackage Jinnah as an Islamic leader in order to increase support and legitimacy amongst Pakistani society and to match their anti-India rhetoric. Not only has there been an attempt to create a new identity, but there has been a concerted effort to downplay and distort Pakistan’s history and Jinnah’s vision. As the New York Times reported from Islamabad in the 1970s, Islamization and appeals to Islam are “a form of therapy to resolve a longstanding national crisis of identity.”

This “therapy” received its fullest expression during the 1970s under the military rule of General Zia-ul-Haq. General Zia, who had come to power after overthrowing Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of the Pakistan People’s Party in a military coup, settled Pakistan’s ideological direction firmly in favor of Islamization, the consequences of which are still being felt today. Take the murders in 2011 of Shahbaz Bhatti, first federal minister for minority affairs, and Salmaan Taseer, governor of Punjab. Both were fierce opponents of the country’s blasphemy laws, which are a source of discrimination against minorities; these laws were enacted under the rule of Zia-ul-Haq during the 1980s.

Yet it was not simply the passing of laws that would define Pakistan’s identity along religious lines. Zia recognized that in order to undercut opposition to his rule by the mainstream political parties in Pakistan he needed the support of the religious far right. He thus embarked on a wholesale program of Islamization, telling a BBC reporter in an interview in April 1978 that he had a mission to “purify and cleanse Pakistan.”

The late 1970s saw a concerted push toward Islamization with the Hudood Ordinances, which replaced the Pakistani Penal code with new offenses of adultery and fornication along with the establishment of Shariat Appellate Benches. Legal cases were now to be judged using interpretations of the Quran and Sunnah, and bought into line with religious sharia law. Islamization was so entrenched that any incoming government that wished to reverse such a process not only had an enormous task on its hands but would also have to contend with the newfound strength of the religious right. For long after Zia’s death, his Islamist agenda lived on through religious groups in Pakistan. Any subsequent confrontation carried with it the charge of going against the new distorted identity of Pakistan.

Any assessment of why liberal democracy has not taken root in Pakistan cannot go without mention of the overall role played by the powerful military in Pakistan. Pakistan has been ruled by its powerful military for half of its 69 years. The seeds of democracy in this fragile state never really had the chance to grow. Unlike its neighbor India, where the army has confined itself to a strictly military role, the Pakistani generals have been far too eager to depose elected governments at will, imposing martial law and shoring up their own position.

Part of the reason for the dominance of the military lies in the fractured nature of the country. Pakistan’s regions are ethnically and linguistically diverse; from its inception the country has had to deal with regional pulls. In Balochistan, which has on occasion been dubbed the site of Pakistan’s secret war, successive governments have had to contend with a separatist insurgency. The government’s writ has barely ever extended to the tribal areas, where at present a militant insurgency rages and Karachi, a city the size of Cairo, finds itself under the clutches of Altaf Hussain’s MQM, with sectarian killings common place.

Historically, given the ethnic diversity within Pakistan, where provinces asserted their own authority and political identities against what they perceived as an encroaching center following the death of Jinnah, the army, as the strongest and most organized institution following independence, was able to step in and fill the void. Not only has it sought to stamp its own authority over the different regions of Pakistan, it has also sought more broadly to define Pakistan’s identity through the prism of security. In order to shore up its position, the military has sought to overplay the threat from India, to ensure the government continues to provide it support both politically and financially. This has further contributed to a Pakistan that has disowned its previous identity in favor of one that is anti-India and stresses the Islamic identity of Pakistan to the detriment of its liberal principles.

Civilian governments in Pakistan have not fared much better. Their failure to fulfill basic state functions, such as providing a decent education and law and order to its citizens, has allowed hardline religious groups to step in with madrassas (religious schools) providing a free education to Pakistan’s poor. Politics in Pakistan is very much like a family business with parties revolving around an iconic leader and their offspring. In more recent decades rule has alternated between Nawaz Sharif’s family and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League (N), and the Bhutto family’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), interrupted by frequent bouts of military rule.

The irony of the name PPP is all too clear, with the leadership of the party being passed on like some hereditary mantelpiece. The party has long been mired in corruption. Although the Bhuttos were never convicted of corruption, many Pakistanis looked upon Bhutto administrations with disdain. The family increased their own personal wealth, holding millions in foreign bank accounts, whilst millions struggled under rising inflation and 24-hour power cuts and poverty.

The Sharif family hasn’t fared any better since Nawaz Sharif’s first stint in office in 1990. When Sharif was removed from power in 1999, many Pakistanis expressed great relief, describing him as corrupt and incompetent. He subverted the judiciary and undermined the press. Many Pakistanis simply do not trust the democratically elected governments, which are tainted with corruption.

The above factors have all contributed to a move away from Jinnah’s original vision for Pakistan. Yet Pakistan as a country is still deciding its fate. Until the nation decides whether it wishes to operate as a Muslim theocracy or as a liberal and progressive state, it will remain gripped in a battle between various forces that seek to advance their own competing visions of what Pakistan should become.

There is, however, cause for optimism. We can draw comfort from the fact that no hardline religious party has ever come close to winning an election in Pakistan. The government and military are united, for the time being at least, on the need to confront the militant insurgency across the country. Democracy is beginning to take root, as one civilian government replaced another for the first time in Pakistan’s history; however, the army must remain in the barracks. It should be welcomed that the current army chief, General Raheel Sharif, intends to step down as planned for November this year. We can only hope his successor follows his footsteps in not playing an active part in politics.

Yet if we are to fully realize the vision of Jinnah’s Pakistan, then the country’s elites must fully embrace the vision that Jinnah set out as opposed to forging new identities to fulfill political agendas and distorting the country’s history. I hope Pakistan’s leaders take heed of Jinnah’s advice: “With faith, discipline, and selfless devotion to duty, there is nothing worthwhile that you cannot achieve.”

Basit Mahmood currently works in public policy research in the U.K. He graduated from the University of Cambridge with a specialization in South Asian politics and has written on a range of issues for the Pakistani newspaper Ausaf.