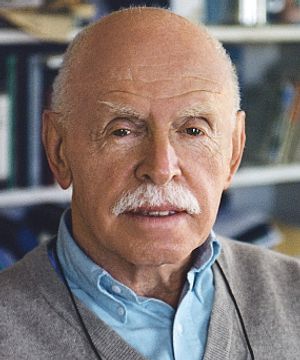

Jerome Cohen is a Professor of Law at New York University and an expert on China’s legal system. In 1972, Cohen first traveled to the mainland and offered advice on China’s legal system to Premier Zhou Enlai. From 1964 to 1979, as Jeremiah Smith Professor at Harvard Law School, he helped introduce East Asian law into the American legal curriculum. Fluent in Mandarin and a senior fellow for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, Cohen has been a tireless advocate of human rights in China. In this interview with The Diplomat, Cohen reflects on law reform during the tenure of President Xi Jinping.

The Diplomat: Where was China coming from under Hu Jintao (2002-2012) and what direction is Xi Jinping (2013-present) taking with legal reform?

Jerome Cohen: The law reform spirit of the earliest years of this century began to die in China during the Hu Jintao era just over a decade ago. It came to an end with the ascension of Xi Jinping, despite the greater professionalization of the judiciary fostered by Xi’s appointment of Zhou Qiang as chief justice. Although the legislative process has sped up under Xi, most new laws produced run counter to liberal legal reforms and are designed to expand the Party’s repressive policies. Moreover, practice, especially in the area of political and civil rights and criminal justice, has become even more repressive than legislation would appear to allow.

The Roman and British Empire laid the foundations for two prevailing legal systems of private law in Europe, namely civil and common law. Looking at China, how is its legal system unique and how is its development influenced by foreign systems?

Although seldom emphasized by the PRC leadership, the country’s legal system is still markedly influenced by the Leninist, Party-controlled system that Stalin perfected and that Mao imported in the period 1949-57. The Bolsheviks built on, and gave a “socialist” gloss to, the pre-1917 Czarist legal system that in the 1860s had been imported from continental Western Europe, largely French and Swiss in content, structure, organization, and procedures. Thus today’s PRC legal system is basically a perversion of the European civil law system easily recognized by continental legal specialists.

However, beginning 1979 with the Dengist reforms, many Anglo-American, especially American, substantive laws have been adapted to China’s needs, blended with other Western influences and engrafted onto the Soviet-style civil law basis, for example in environmental, securities, and labor law. China is now unique among economically significant countries in the extent to which it has crushed independent lawyers. Xi Jinping, who occasionally invokes the influence of China’s millennial legal traditions, seems to favor adopting the most repressive aspects of China’s legal tradition that emphasized law and punishments as instruments of state control rather than restraints upon arbitrary government conduct.

Xi Jinping has initiated a campaign to combat corruption in China. Do you think this is being done on an even basis, no matter whether a person is a friend or foe?

Although thousands of allegedly corrupt officials have been prosecuted for corruption, certainly at the higher levels the campaign has focused on political enemies of the dominant players. Many other high level targets and their families and associates have thus far been spared.

What is the relation of the Party to the legal system and how do you assess judicial independence in China?

The Party totally dominates the legal system, including the education, training, and day-to-day operation of its personnel and institutions. “Judicial independence,” as it is commonly understood outside China today, is the enemy and forbidden by Party rulers even to be discussed in law schools. The term is only used in a positive way in Beijing to describe efforts to insulate local prosecutors and judges from local influences including corruption, social connections, local protectionism, and other forces that divert local legal officials from following the central Party authorities’ instructions.

How are human rights faring under Xi Jinping?

Xi Jinping’s actions regarding the legal protection of political and civil rights have been increasingly repressive in practice. His continuing brutal suppression of human rights lawyers and their families and colleagues has been scandalous, relentless and cruel.