Recently, Indian multinational conglomerate the Tata Group inaugurated a new office in Myanmar, and is likely to expand its operations in Southeast Asian countries. Some Tata companies already present in Myanmar include Tata International (which trades in agricultural commodities such as pulses and beans and other commodities including fertilizers), Tata Consultancy Service, Tata Motors, and Tata Power, which is actively exploring opportunities in the renewable energy space.

The Tata group needs to be lauded for the fact that it has been very strategic in not restricting its business operations to natural resources. In seeking to enter areas like the information technology (IT) and agricultural sectors it has sent a clear message that, unlike Chinese companies, Indian companies are not merely interested in grabbing natural resources and are keen to create opportunities for locals and help in capacity building.

Myanmar, with whom India’s ties have been strengthening over past decade, is India’s land bridge to Southeast Asia. With Myanmar’s government trying to encourage foreign investment, and with the recent removal of U.S. sanctions, it is likely to emerge as an important investment destination. Given the geographical proximity to India, strong political links between both countries, and the growing angst against Chinese businesses, Indian investors have a chance to take the lead in Myanmar.

At the moment, Indian investment falls way behind that of China. While Indian investments for 2015-2016 were estimated at $224 million, Chinese investment over the same period totaled over $3 billion. However, Myanmar itself is keen to reduce its dependence upon China and look for alternatives. Unlike Chinese investors, there is not much resentment against Indian investors either in Southeast Asia or Africa, since they generate local employment.

A number of important infrastructural projects, such as the India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway and the Kaladan multimodal project, are being expedited are bound to improve connectivity between India and Myanmar, and from there to the rest of Southeast Asia. There are also plans to further strengthen air connectivity.

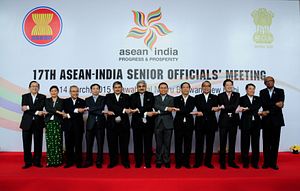

It is not just Myanmar, however. India’s economic ties with ASEAN in general, and the CMLV (Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam) countries in particular, have witnessed a sharp rise. Bilateral trade between India and CMLV countries was just $460 million in 2000, and increased to $11.85 billion by 2014. Of India’s total trade with ASEAN, over 15 percent is with CMLV countries, which have less developed economies compared to the fellow ASEAN members.

India is also encouraging companies to invest in CMLV countries. A Rs. 5 billion ($75 million) Project Development Fund has been approved by the Government of India for encouraging Indian investments in CMLV countries.

Private sector companies like Tata themselves are according high priority to CMLV countries, seeing their potential. In addition to Myanmar, Tata has been expanding their operations in Vietnam. The fact that these countries are engines of growth, have favorable demographics, and are signing free trade agreements with different regions are encouraging the private sector to tap CMLV industries. This is a significant change from earlier, where Singapore was considered to be India’s gateway to Southeast Asia, due to the strong political and economic ties as well as the positive role of the Indian diaspora.

While India’s presence in CMLV countries may be increasing, a number of steps need to be taken to make this policy more effective. Nirmala Sitharaman, speaking at the 3rd India CLMV Business Conclave at Chennai, remarked, “The trade links and ties between India and the CLMV countries can be much better and the two governing principles, connectivity and economic integration with regional value chains, are crucial.” The first step is stronger air connectivity, expediting infrastructural projects between India and Myanmar. Apart from this, people-to-people contact between India-Vietnam and India-Myanmar also needs to be enhanced to generate goodwill for India.

Second, while Prime Minister Narendra Modi has on more than one occasion spoken about the benefits for northeast India, there has to be a clear vision for benefiting the northeast itself, beyond its role as a connector. Before encouraging private players to invest in CMLV countries, the government should urge more private entities to invest in India’s northeast.

Finally, the Indian government should not shy away from taking up issues that Indian investors face in other countries. For a long time, the Indian government has not been aggressive enough in pushing the interests of Indian companies whenever they have had problems.

Indian companies has strong potential in CMLV countries but the government and private sector need to work closely together. While the government should back Indian businesses, the latter needs to exhibit more of a risk appetite and not shy away from investing in transitioning societies.

Tridivesh Singh Maini is a New Delhi based Policy Analyst associated with Jindal School of International Affairs, OP Jindal Global University (Sonipat). His areas of interest include India’s Act East Policy.