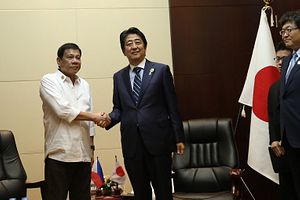

Rodrigo Duterte, president of the Philippines, is visiting Japan this week. Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida is hosting a dinner for him on October 25, followed by a more formal bilateral meeting with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on October 26, where Abe is expected to sign an agreement to provide additional two patrol vessels to the Philippines. In addition, as an unusual gesture of welcome, Abe will meet Duterte one-on-one in his residence on the night of October 26. Duterte is even scheduled to have a courtesy call meeting with Emperor Akihito on October 27.

Clearly, the Abe government decided to roll out a red carpet for Duterte. To some observers, this is at minimum awkward. Duterte is arriving in Japan after his visit to China, where he received a very warm reception. Since Duterte’s inauguration in June this year, there has been a mounting concern about the future of the U.S.-Philippines alliance, especially given the new president’s outreach to Beijing. Such concerns were only aggravated as Duterte increased the tone of his criticism against the United States, including referring to President Barack Obama with a derogatory term. Earlier this month, he openly contemplated walking away from the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) that Duerte’s predecessor, President Benigno Aquino, signed with the United States. Although Duterte tried to “clarify” what he meant, his recent comment that his country will “separate” from the United States was met by a great deal of concern in the United States, with the White House describing his comments as “confusing” and “offensive.”

Knowing the level of importance Abe attaches to a robust U.S.-Japan alliance, his government’s warm reception of Duterte appears, at a first glance, perplexing. To be sure, some will undoubtedly point to Abe’s decision to move ahead with Japan’s gift of patrol vessels and planned loan of aircraft as mistakes, out of the concern that his government’s move may be seen as rewarding Duterte’s provocative behavior, particularly vis-à-vis the United States, and his hasty rapprochement attempt with Beijing.

However, Abe’s effort to reach out to Duterte may turn out to be effective in preventing a fundamental shift in Filipino foreign policy. Duterte has not spoken ill of Japan, or Abe himself, since he came into the office. This makes it easier for Japan to come through to Duterte as a friend of the Philippines that respects him as the leader who has been democratically elected by its people.

While following through on Japan’s commitment to strengthening the Philippines’ coast guard capacity may look like a lost cause in the short run, the cost of not helping the Philippines to build its maritime capacity will be larger. Despite Duterte’s rhetoric, government officials in Manila are fully aware of the critical importance of their country’s relationship with the United States. Should Japan, a fellow U.S. ally, turn its back on Manila when Filipino officials are trying to salvage the Philippines’ relationship with the United States and the West in general, it would simply aggravate the sense of desertion already felt by some in the Philippines, and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy by sending Manila deeper into China’s arms. Japan needs to stay as the Philippines’ “friend in need,” especially in a challenging time for U.S.-Filipino relations.

While awkward, Duterte’s visit to Tokyo can be a great opportunity for Abe to be instrumental in minimizing the damage of Duterte’s rhetoric. In fact, how well Japan can maintain its relationship with Manila may be essential in preventing Duterte from implementing the fundamental reorientation of Filipino foreign policy.