Myanmar’s explosive economic growth and untapped potential have led many investors to dub the country as “Asia’s final frontier.” The “opening up” of the country, first set in play in 2011 with a set of transformative economic and political reforms by the previous government of Thein Sein, caught much of the world off guard – and with good reason.

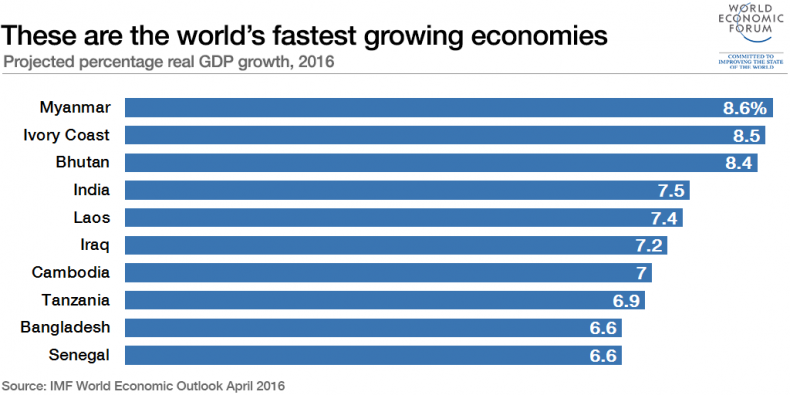

After decades of isolation and a ruinous period of brutal military dictatorship, Myanmar finally came in from the cold. To the world’s further surprise – and to give context to just how fast the pace of reform has been – nationwide democratic elections last year pushed the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) from power, with a government led by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) taking office in April; Myanmar’s first truly civilian-led government in over half a century. In less than six years, the country has come from international isolation, pariah status, and a 2010 general election that the UN dubbed “deeply flawed” to become Asia’s newest fledgling democracy and the world’s fastest-growing economy, according to the IMF.

Despite breakneck economic growth of around 8 percent year-on-year, the country faces serious challenges and a lot of catching up to do. Sixty years of economic isolation and mismanagement has left a mark. Myanmar is the poorest country in Southeast Asia, has the lowest life expectancy, and the second-highest rate of infant and child mortality. Basic infrastructure also presents a huge challenge, with just one-third of the population having access to electricity and road density standing at just 220 kilometers per 1,000 square kilometers of land, according to figures from the World Bank. A lack of clear land ownership, difficulties accessing commercial credit, poor port and road infrastructure, and a large skills gap also top the laundry list of investor gripes.

The Clock Is Ticking

The challenges may be many, but the opportunities are greater still. Young demographics, cheap labor costs, huge untapped domestic consumption with a population of around 60 million, and the geographic advantage of being the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia – sandwiched between the Asian giants of China and India – make Myanmar well positioned to reclaim its crown as a regional trading hub. Colonial Burma was once the richest and most advanced country in Southeast Asia, with Rangoon serving as Britain’s primary trading port and transport gateway to the region. A rich endowment of natural resources – including minerals, oil and gas, teak wood, and agricultural products – add to the bright prospectus for adventurous investors and entrepreneurial businesses seeking new markets and areas of growth.

Robert Easson, CEO of the British Chamber of Commerce in Myanmar, is bullish on the country’s potential and scathing of investors who continue to “wait and see,” saying that foreign investors and businesses are “now running out of excuses” not to do business in and with Myanmar.

At the beginning of October, the U.S. government removed all remaining major sanctions on Myanmar, including, and crucially, restrictions on the banking sector – therefore laying the foundations for Western banks to reengage in the country and for Myanmar to regain full access to the international financial system.

Correspondingly, the NLD government has been busy pushing through economic reforms, including the passage of a new investment law, which will combine and replace the overlapping foreign investment and Myanmar citizen’s investment laws. The new law will simplify the investment process and allow the government to use tax breaks and other incentives, such as establishing special economic zones, to make targeted regions and sectors more attractive for investment.

Aung San Suu Kyi, in her position as state counselor and de facto head of government, has also spent the last few months on a global promotional tour, with stop overs in China, India, Japan, the U.K., and the United States, to pitch the country to foreign investors and further economic ties. Over the last few weeks, and with the end of sanctions and the new investment law in place, Suu Kyi convened an audience of foreign businesses and investors in Naypyidaw to further drive the message home and make the case that economic development is crucial for advancing the country’s democratic institutions.

On the horizon, and something that many Myanmar analysts are more eagerly awaiting, is the passing of the new companies act, which looks to bring Myanmar up to international standards and replace the existing act – which dates back to colonial-era legislation from 1914. The new companies act looks to further modernize the business environment, bringing Myanmar in line with basic international standards of corporate governance and frameworks, with provisions including the strengthening of shareholder rights, outlining the responsibilities of company directors, and crucially – and perhaps the real hidden game changer – the possible loosening of laws to allow foreign entities to obtain long-term land leases and titles. Land rights have been a major stumbling block for many investors, not to mention disputes over land title ownership.

The new companies act will also massively reduce compliance costs and regulatory burdens for firms, with the cost of doing business in Myanmar frequently underestimated by investors coming into the market. Combined with another provision that may allow foreign investors to buy shares on the Yangon Stock Exchange, Aung Naing Oo, the director general of the Directorate of Investment & Company Administration (DICA), was upbeat on how these reforms would modernize and simplify business processes.

These types of modernizations are of course badly needed in Myanmar. The World Bank’s global ease of doing business rankings, currently scores Myanmar at the bottom end of the table – at 170 out of 190 countries globally – far behind neighboring countries such as Laos, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam, and more than a hundred places behind next door neighbor and regional export leader, Thailand, which comes in at a global ranking of 46. Myanmar still has a very long way to climb to catch up with its neighbors, but the country is in a hurry to make up the gap. After a significant investment slowdown last year, in which many investors, especially Western firms, waited to see how the elections played out and the new government shaped up, many businesses, especially from Asia, are now queuing up for permits and positioning themselves to take “first mover advantage.” The clock is now ticking for those wanting to get in on the country’s economic opening.

A Good Signal

Although behind their Asian rivals, Western multinationals are certainly taking advantage of Myanmar’s progress and potential. TODAY Ogilvy & Mather, one of the country’s biggest advertising and public relations firms, and part of the global WPP marketing group, is seeing a number of big brands enter the market, such as helping to introduce KFC to the country last year. Shell, Coca-Cola, and Nestlé are other big names on their client roster that are working to build brand awareness and increase their in-country profiles.

Perhaps most indicative, though, of the “win-win” that greater economic openness and foreign investment has brought to Myanmar can be seen in the country’s rapidly developing telecommunications sector. Gaining licenses in 2013, Norway’s Telenor and Qatar’s Ooredoo have sunk multimillion dollar investments into the country over the past three years, and now dominate the mobile market. The liberalization of the sector and subsequent investment in towers and telco-technology infrastructure have increased mobile and internet penetration vastly. Mobile and internet coverage in the country has leap-frogged from less than 20 percent and 10 percent, respectively, in 2014, to 60 percent and 25 percent today, allowing millions of people in Myanmar to access information online through 3G and even some 4G covered areas, and make calls at affordable prices for the first time.

This particular sector is symptomatic of the broad sweep of changes and rapid boom in development that the country is now experiencing. Mobile sim cards are now available across the country, sold in shops and roadside street stalls for a mere 1,500 kyat or around $1.50. This would have been unthinkable just ten years ago, when mobile ownership was off-limits for all but the elite, with a sim card setting a well-heeled or well-connected buyer back by more than $2,000 – and even at that price, reception was patchy.

Hidden Gems

As a new “frontier” market, almost every sector is seeing growth, but certain areas are faring better than others. GAP and H&M have been quietly doing business in the country for a number of years now, with basic textile factories on the outskirts of Yangon. These multinationals benefit from Myanmar’s low cost of labor, as wages across the region, especially in China, rise – highlighting the country’s next “factory floor” potential.

Beyond resources and manufacturing, it is the service sector which is seeing the fastest rates of growth – in big demand in a country where the advancement of modern services ground to a halt with the junta’s coup and subsequent nationalization of the economy. Education and healthcare are such specialist areas where Western businesses are seeing a gap and filling it. Recent entrants include leading U.K. independent school group, Dulwich College, which in April announced its entry into Myanmar with two campuses in Yangon, funded by a capital investment of more than $30 million by Singapore-listed Yoma Strategic Holdings. Global private healthcare provider, International SOS, is also growing its presence in the country, as a lack of adequate healthcare blights the nation. The suits are also in town, with Western multinational service firms all scooping up good business in the country. Deloitte, Ernst & Young, and PwC all have a presence in Myanmar, doing the all-important due diligence and auditing that new investors require, vetting suitor projects and potential local business partners, as more firms expand into the market.

Perhaps surprisingly in a “frontier” Asian market, it is the upmarket Anglo-American legal firms that are seeing some of the most significant growth, making the most of the multiple deals and transactions now being carried out. Global law firms Baker & McKenzie and Allen & Over both have a presence in the country. For Easson, it is Myanmar’s British-based “common law” legal system that may well be the country’s secret weapon and an often overlooked advantage in making the country favorable to Western investors, ahead of other neighbors in the region, who mostly have different legal systems. Many Western firms, after first experiencing significant initial growth, have often found it difficult to traverse the complexities of alien and opaque legal and regulatory frameworks in the region, whereas Myanmar’s law, as is the case in Singapore and Hong Kong, is essentially based on British law. Easson says “this gives those companies with similar legal systems – most notably U.S. and U.K. companies – a distinct advantage of ‘being at home’ within the same legal framework.”

Back to the Future

As one would expect in a country largely cut off from the world for decades, the development of technology services and ICT infrastructure is well behind that of Myanmar’s neighbors and presents a huge area for potential growth, but also a huge headache for businesses operating in the country. The government, too, is looking to ICT and e-government systems to improve and modernize antiquated government bureaucracy and is setting up a dedicated committee to put more government services online, in an attempt to replicate the successes of neighboring countries’ e-governance systems, such as Thailand.

Although a weak IT backbone and a lack of skilled expertise in the sector presents a real challenge, the government’s commitment to modernization through technology has already been realized in Myanmar’s highly successful “e-visa” program, built with the support of Singapore. Now tourists and business travelers from outside ASEAN can apply for, pay for, and receive their Myanmar visa online – usually within a day. Here again, Myanmar is jumping ahead of many other more established countries in the Asia region, which often have notably more trying visa and permit restrictions. It is this type of “small win” that is making many in Myanmar’s business community hopeful that, despite the challenges, the country is very much on the right track to further ease doing business and attract ever growing investment in the years ahead.

Despite a past history of asset seizures and currency revaluations under junta rule and decades of financial sanctions, which led all major foreign banks to leave the country, Myanmar is now seeing many returns. Some Western banking and insurance companies have been patiently persevering over the last few years, softly reestablishing themselves in the country and waiting for the chance to jump back in, when sanctions are eased and foreign business permits permitted. Standard Chartered, which can date its heritage in Myanmar back to colonial Rangoon – when the city used to be a financial hub for the British East India Company – has had a representative office in the country for a number of years. Insurance giant, Prudential, also has been building its presence. Although both financial heavyweights do not yet possess operating licenses, nor are they commercially active, their representative offices have been busy establishing networks and relationships, working on a number of “ground-laying” initiatives to educate and improve capacity in the financial sector – such as joint capacity-building initiatives with the government and financial literacy programs aimed at educating the public. Both hope, and are looking to receive, operating licenses over the next year, reaping the benefits after many years of slowly building up their presence.

Exponential Potential

Although the new government is young and inexperienced, many in Yangon’s business circles have been positively surprised by how receptive the government has been. Despite huge disadvantages – with a government administration that lacks experience, expertise, and funding – Easson says that what is different in Myanmar, in comparison to other countries in the region, is that the government does not just pay lip service to business complaints and recommendations, but acts on suggestions and then implements them in practice. While foreign businesses in neighboring countries, such as Vietnam and Indonesia, have fallen foul of nationalist and protectionist policies of late, Myanmar’s government and its people have been more welcoming of foreign businesses – especially after decades of being left on the sidelines of Asia’s economic ascent and global trade. Institutions such as the World Bank, International Finance Corporation, and Asian Development Bank have also found a greater willingness from the government to listen and engage. The recent investment law, for example, had considerable input from the business community and international institutions in its drafting.

Despite starting from a low base, the general sentiments from economists, analysts, and businesses active in Myanmar today reflect optimism about the future. Consumer consumption alone has been skyrocketing over the last year, as Myanmar’s people start to consume the branded foreign goods and products now flooding into the market, from shampoo to snacks.

For those willing to take the plunge, deal with the difficulties, and invest for the long haul, Myanmar now looks to be on the path to a prosperous future and a fast-growing, dynamic economy. More importantly though, it is Myanmar’s people that are now experiencing the benefits that greater political freedom and economic growth is bringing, from jobs to development. It is for this reason that Myanmar is now past the point of no return. The genie is now well and truly out of the bottle.

Edward Parker is a contributor to The Diplomat, based in Southeast Asia.