This article was first published at 38 North, a blog of the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins SAIS. It is republished with kind permission.

North Korea’s rapid nuclear and missile development has intensified the debate over the efficacy of U.S. and South Korean policies toward Pyongyang. Comparing North Korea’s weapons development to China’s own arms activities can contextualize these discussions, in part by highlighting the remarkable speed with which North Korea has accomplished its recent technical milestones. Moreover, two other considerations drive this comparison: allegations of recent Chinese technical assistance to the North and their common geopolitical interests. While both China and North Korea share the need to project a nuclear deterrence capability against the United States in the Pacific, it appears that Chinese assistance in this process has been largely indirect. The picture that emerges from this discussion also suggests that rather than being dependent on Chinese technology, Pyongyang’s tremendous progress may in fact be the result of persistent trial-and-error on overdrive, an effort which will accelerate the emergence of new and dangerous threats.

Side-by-Side: North Korea and China

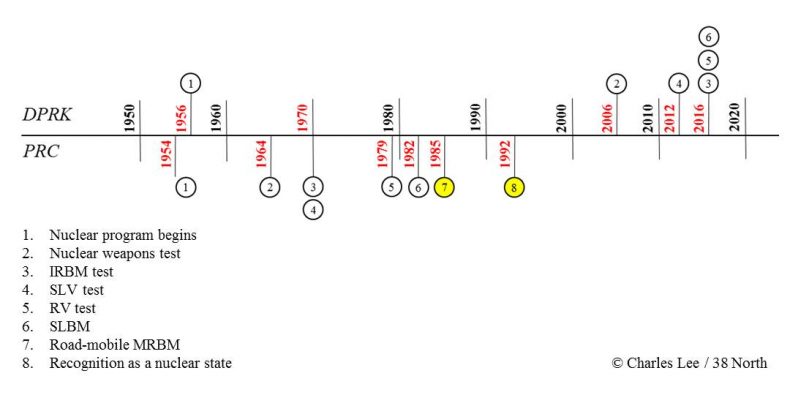

By comparing North Korea’s and China’s key nuclear and missile development milestones, we can benchmark Pyongyang’s progress to date and assess its future development trajectory (see the chart below. The framework below incorporates four key events: 1) commencing nuclear development; 2) conducting an initial nuclear test; 3) developing the means to deliver a nuclear payload; and 4) attaining recognition as a nuclear weapons state. The timeline further expands the third phase — developing a means of delivery — into additional components: successful initial testing of an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), a space launch vehicle (SLV), a re-entry vehicle (RV), a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), and a road-mobile long-range missile platform. This broad comparison yields several important insights discussed in the next section.

A timeline of DPRK/PRC nuclear/missile development milestones. Highlighted numbers represent achievements only attained to date by the PRC.

Two Peas in a Pod?

North Korea’s and China’s nuclear and missile development programs are similar in their sequencing of key milestones, but differ in their rates of progress. The first and most striking difference between the two timelines is the significant acceleration of North Korea’s advances in the past year. The passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2270 in March 2016 may have helped to precipitate this dramatic surge in development. Political opportunity could be another contributing factor. Pyongyang may be intentionally consolidating its gains within a short timeframe to exploit political gridlock stemming from a lame-duck presidency in Seoul and a presidential election in Washington. However, it is still unclear how the North has significantly outpaced China’s historical nuclear and missile development.

Some analysts are skeptical that Pyongyang could have achieved success at such an impressive rate without aid from a more technologically capable benefactor — namely, China. These analysts have noted similarities between the KN-11, North Korea’s indigenous SLBM, and the Chinese-made JL-1. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that China offered the North direct technical assistance in recent years. As Henry Kissinger once stated, Beijing is fully aware of the costs of complicity in helping advance Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons program. A nuclear North Korea risks the nuclearization of East Asia — most notably, Japan and South Korea. Such proliferation would shift the balance of military power in Asia, boding poorly for Chinese interests.

China has, however, tolerated indirect assistance to North Korea that likely helped to accelerate its nuclear and missile program. The recent U.S. indictment of Ma Xiaohong, the CEO of Dandong Hongxiang Industrial Development Company, demonstrates both the scale and nature of Chinese complicity. By one estimate, the Hongxiang Group’s trade with North Korea totaled in excess of $500 million over the last five years. The concern is that the company’s subsidiaries have exported dual-use commodities with nuclear and missile applications. Beijing’s early cooperation on this matter suggests that it may not have provided direct support to Pyongyang’s weapons program and that it is willing to enforce the U.S. Treasury Department’s sanctions against North Korean companies, at least for the time being.

Another distinguishing feature of North Korea’s arms development is the long period between the initiation of its nuclear program and its first nuclear weapons test. From a policy perspective, this makes sense. Developing a credible strategic nuclear deterrent was not a core objective for Pyongyang during Kim Il-sung’s rule. The elder Kim first promulgated the byungjin line of parallel economic and military development in the 1950s. Under Kim Jong-il, songun politics began in the 1990s to emphasize the centrality of military strength to the regime’s survival. Nuclear weapons therefore factored heavily into realizing songun policy. The prevailing belief among North Korean leadership was that only nuclear capabilities could counterbalance the tremendous weight of the U.S. and South Korean military alliance. Kim Jong-un’s approach is something of a hybrid of the two preceding generations. His revival of the byungjin line restored Kim Il-sung’s emphasis on dual military and economic development, but it also specified the necessity for developing more capable nuclear means.

A third difference, and a major source of contention and speculation, is whether North Korea has mastered re-entry vehicle technology. China developed and successfully tested an RV prior to its successful launch of the JL-1 SLBM in 1979, and North Korea claims to have completed similar testing in March 2016. However, there are significant differences between each nation’s RV development. Chinese scientists spent over a decade improving missile nosecones to protect nuclear payloads. Moreover, this was accompanied by robust in-flight testing. North Korea has so far only conducted ground-testing of RVs, and many analysts speculate that its trials to date may not have achieved the conditions necessary to demonstrate workable RV technology. Of course, outside observers have long underestimated North Korea’s technical abilities.

With the exception of its steps to master RV technology, North Korea has yet to test its elusive road-mobile KN-08. Notably, Chinese technicians were able to effectively convert an earlier land-based version of its JL-1 into a solid-state, road-mobile DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM). In August 2016, North Korea’s KN-11 achieved flight success using similar solid-state fuel technology. Could North Korea’s promising results lead to success for its road-based missile system as in China? If so, how soon? Much like its accomplishments so far, it may only be a matter of time. The United States and South Korea should certainly be wary of this outcome. Successful development of a KN-08 could offer North Korea a significant and valuable coercive bargaining tool in any discussion regarding the status of its nuclear weapons program. Worse still, systems like the KN-08 could embolden North Korea to turn its attention to a new generation of capabilities, perhaps again following in China’s footsteps.

Assessing the Road to Future Progress

As the comparison above illustrates, North Korea’s core weapons capabilities are reaching an apex. Even more concerning is the fact that North Korea’s relentless trial-and-error — not Chinese technical assistance — is principally generating its positive momentum. For policymakers in Washington and Seoul, the comparative analysis of Chinese and North Korean weapons development highlights the urgency of reevaluating North Korea policy before it has perfected its nuclear and missile technologies. While Pyongyang seems to be headed rapidly down the track Beijing has already traversed, this comparison is not meant to suggest a single culminating point in weapons development. One should hope, though, that the comparative timeline used here does not continue into the future, or else the United States will be faced with significantly greater challenges.

Charles Lee is an intelligence officer in the United States Marine Corps and a graduate of Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. He provides intelligence support to Korean theater operational planning for III Marine Expeditionary Force. The views expressed are of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Marine Corps or Department of Defense.