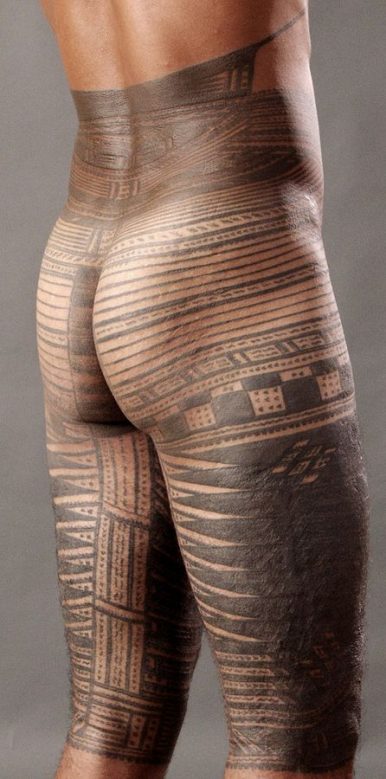

Receiving a tattoo in the traditional Samoan way was an excruciating experience. As a rite of passage, men were expected to undergo up to three or four months of inking. During a session, which lasted until dusk or until the pain was unbearable, an artist tapped designs into the skin with a mallet and tattoo comb dipped in ink, following simple marks as a guide.

The man’s family threw a party to celebrate the completion of his pe’a, or tattoo that stretched from mid-torso to the knees, and the tattoo master shattered a water vessel at his feet to signify that the agonizing experience had come to an end.

Then came the healing process. The man’s wounds were washed in saltwater and his body was massaged for months to keep infection and impurities at bay. Even everyday tasks could trigger searing pain. But within half a year, the designs would begin to emerge on the skin, and within a year he would be fully healed.

The ordeal was so severe that death by infection was a legitimate concern. But social pressure ensured that most men completed the process, lest they be considered cowards and shunned by other members of the tribe. Those who succumbed to the pain wore their incomplete ink as a badge of shame for life.

Unlike the modern-day experience of entering a tattoo parlor, discussing a desired design with a tattoo artist, and going under an electric needle for perhaps a few hours, the ordeal was the norm in ancient Polynesia, where tattooing was fraught with taboos, steeped in social status, and imbued with deeply spiritual beliefs. Following a long period of religious repression, stretching from the mid-19th century through the 1970s, tattoos are once again a vital element of Polynesian culture and serve as potent spiritual symbols for those who wear them.

“I have strictly Polynesian tattoos,” Charles “Didjelirium” Perez, a Tahitian documentary filmmaker, told The Diplomat. “I got my first tattoo for my 14th birthday, and I’ve been adding more ever since. It’s a single arm band that depicts the circle of life, from birth to adulthood to death to reincarnation.”

A Brief of Polynesian Ink

Stretching from New Zealand in the southwest and Easter Island in the southeast to Hawaii in the north, the Polynesian (“many islands”) Triangle spreads across a large swath of the central and southern Pacific Ocean and includes more than 1,000 islands. Legendary sailors who were adept at navigating by the stars, Polynesians left their ancestral home of Taiwan sometime between 3,000 and 1,000 BCE and began to explore and inhabit some of the most remote slivers of land on earth.

The intrepid voyagers created a rich tapestry of cultures, with tattoos featuring prominently among them. It is indicative that the English word “tattoo” comes from the Polynesian word tatau, used from Tonga to Tahiti, which the British explorer James Cook brought back to England following his journey to Polynesia in 1771. A tattooed Tahitian named Ma’i also accompanied Cook back to England, causing word of the ink arts to spread across Europe.

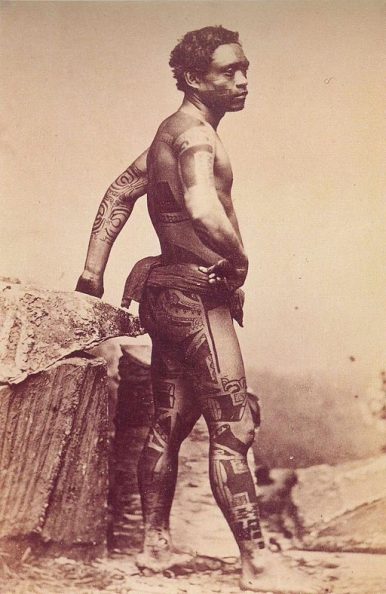

While tattoos were an exotic curiosity in Europe, in Polynesia tatting up served a variety of important functions. Writing did not historically exist in Polynesian culture, which made tattoos an important form of communication indicating social status, sexual maturity, genealogy, and rank. Given the hierarchical nature of ancient Polynesian society, this meant that almost everyone was inked, from the Samoans to the Tongans and the Maori of present-day New Zealand.

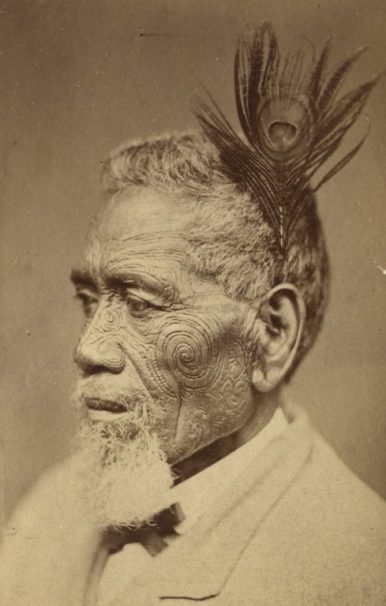

A traditional Samoan make tattoo. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / CloudSurfer

While Polynesians have been inking up for more than 2,000 years, tattooing was elevated to an art, loaded with spiritual and social charge, most notably in Tonga and Samoa. In Tonga, warriors were inked with geometric patterns — triangles, bands, areas of solid black — from the waist to the knees. Samoans would be tattooed from the waist to below the knees in groups of six to eight — mostly men — as friends and family looked on. Some Samoan women also wore flower patterns on their hands and lower parts of the body.

“Samoan and Maori tattoos are probably the most significant tattoo styles from Polynesia today, based on how much we see them in the media in general,” said Jean-Philippe Joaquim, an anthropologist and director of the documentary film, Tatau, the Culture of an Art. “But the visually strongest style is definitely Marquesan, which has these big patches of deep black that are really impressive.”

Perez added: “What I love most about Polynesian designs is they may look like random lines and shapes and have a tribal feel, but each symbol actually has a meaning. Some designs are just not obvious, like an eagle or a tiger. Even though I enjoy looking at colorful artwork on people’s skin, my favorite style is still black.”

Spirit and Society

Across Polynesia, there are a wealth of tattoo origin stories. The one point they all agree on is the belief that tattoos are a gift from heaven to humankind. According to Tahitian legend, the sons of Ta’aroa, the supreme creator, were the first beings to tat up. Ta’aroa’s sons, in turn, taught the ink arts to men who relished the new form of self-expression. Matamata and Tū Ra’i Pō, both sons of Ta’aroa, were made the patron gods of tattooing.

The ink designs themselves were also considered highly sacred. The patterns and placement on the body differed between island chains, but some motifs were believed to preserve one’s mana, or divine essence, which was believed to preserve one’s health, sense of balance and fertility.

“My tattoos are all protection signs, symbols of nature and the world around us,” Perez said. “They are meant to help gather more mana, or life energy. I have a wave shape and arrows on my right arm to give me more power and energy flowing to my mic while performing vocals.”

Along with the spiritually charged beliefs surrounding the body across Polynesian cultures, a series of taboos arose around the process of giving and receiving tattoos. Captain Cook also introduced the word “taboo” to the English language, upon returning from Tonga where he heard it being used (as “tapu”) to describe all manner of things forbidden.

Among the Maori, for example, both the one being tattooed and the artist carrying out the sacred art were forbidden from eating with their hands or speaking with anyone besides others being tattooed. Other Maori rules included abstaining from sex during the process and avoiding solid foods. The one being inked would be fed via a wooden funnel to keep food from falling into the swollen lines rising from the skin.

Besides taboos, the placement on the body is crucial across Polynesia, with the lower body connected to the earth and worldly matters and the upper body turned to the spirit world. For example, a tattoo on the head related to spirituality, knowledge, and intuition, while a design etched into the lower arms and hands connected to matters of creativity and creation.

Some popular motifs included shark teeth, spearheads, waves, tiki figures, turtles, and lizards — each containing a meaning of its own.

As American anthropologist and tattoo expert Lars Krutak wrote in his excellent introduction to Polynesian tattoos, the complex system of symbols and patterns found across the archipelagos are “veiled in a system of interrelationships between symbolic opposites (e.g., life and death, darkness and light, impermanence and permanence, etc.) that both accounted for and regulated the positive and negative forces held responsible for the origins of the Polynesian universe and the act of human creation, among other things.”

In Maori culture, the facial tattoo (moko) was most significant, as the head is considered the most sacred part of the body. Only Maori with noted social status were allowed to don such tattoos, which were given to them by men called tohunga tā moko (“tattoo specialists”). Tohunga used what was called an uhi, or a wooden-handled chisel made from albatross or whale bone, which they hit with a mallet to create the distinctive Maori designs that resemble grooves in the skin.

Maori with enough social standing to tat up had their faces marked to indicate rank and give a visual run-down of one’s accomplishments, position, ancestry, and marital status, among other pieces of socially relevant information. Their inky masks contained spirals and curvy shapes, divided among eight sections of the face, each imbued with its own meaning. Maori women also wore lighter tattoos on their chin, lips, and nostrils.

The art of moko was so revered that the heads of prominent figures were preserved after death as mokomokai. When possessed by families of the deceased, mokomokai were kept in ornate boxes and treated with great honor. The mokomokai of a deceased leader was believed to allow them to remain active in the community.

On the darker side, mokomokai were also taken as trophies of war and even sold to early European explorers who saw the heads as curiosities. The market for Maori heads peaked during the Musket Wars of the first half of the 19th century, but was finally banned in 1831 when General Sir Ralph Darling, governor of New South Wales, put an end to the macabre trade.

From Repression to Rebirth

Polynesia’s long history of inking up was interrupted in the early 19th century, when Christian missionaries began to arrive on distant Pacific shores. The arrival of the foreign faith had a dramatic impact on the native spiritual beliefs of Polynesia. The tattoo traditions of some Polynesian islands such as Tonga and Tahiti were all but wiped out by Old Testament-inspired bans imposed under missionization and colonial rule.

There was resistance to be sure, most notably from the Tahitians who carried out a number of “tattoo rebellions” from the early to mid-19th century to assert their sovereignty and religious roots. A band of bards, priests, poets, and historians known as the ario’i led the movement, bolstered by social proof derived from their commitment to their patron deity ‘Oro, the god of war, for whom they threw lavish festivals.

Taking a slightly different approach to the ban, the chieftains and elite of Tonga simply made the trip to Samoa, where missionaries held less sway and tattoo artists plied a brisk trade underground. Tattooists operating on the island of Savai’i, Samoa’s largest, accumulated great wealth thanks to the glut of Tongans coming to their shore in search of ink.

This state of affairs continued to varying degrees across much of Polynesia until the 1970s and 1980s, when tattoos experienced a cultural rebirth just as they were in danger of being lost altogether.

“Tattooing in French Polynesia was reborn by the end of the 1970s, but by that time ancient patterns and meanings were completely lost,” Joaquim said. “When people began to reappropriate tattoos, they used what was documented by a few German and American scientists [from the 19th century].”

Contemporary Polynesians who choose to be inked are making “a personal act of commitment to Polynesian culture,” Joaquim said. “Everyone can get a tattoo and put into it the meanings and beliefs that they want. This is no longer the choice of the community. Today, this is your choice.”

This renaissance was part of a greater awakening of cultural identity, accompanied by a renewed interest in other practices like firewalking, chanting, and dance. This return to roots was largely spurred by scholars, researchers, and visual artists. Of note was the role played by Tavana Salmon, a former Waikiki nightclub owner, and Teve, a Marquesan dancer, who traveled to Germany in 1981 to research traditional tattoo designs.

On their way back to Tahiti they stopped in Samoa, where the tattooing techniques of old still survived. In Samoa, they arranged for a tattoo artist to visit Tahiti to tattoo Tavana with Tahitian designs and give Teve a full-body Marquesan tattoo — using sketches from the journals of early Western explorers. Tahitian artists then reconstructed their own tools and techniques by watching Samoan artists work.

Aside from a 1986 ban on traditional tattooing methods in French Polynesia — aimed at staving off infection via wood and bone tools, which are difficult to sterilize — the ancient tradition is flourishing once again. Joaquim estimates that in Tahiti today, they are maybe four or five tattoo artists using the traditional method — sterilized, of course — which was reintroduced by Samoan artists.

But not all Polynesians have embraced tattoos equally. “Even though the world is changing, and people are becoming more educated, the religious will not change what is written in their books,” Joaquim said. “But the church has had to tolerate tattooed people. If they hadn’t done that, it would be a sad thing to see on Sundays today.”

Amid all this change, some Polynesian tattoo artists have begun to put a new spin on the ancient art. “Through different cultures sharing from around the Pacific, a fusion style has developed,” Joaquim said. “Today it is not rare to see Marquesan, Maori, Modern Tahitian, Hawaiian, and Samoan tattooing mixed into one tattoo. Some artists also use Japanese motifs, add colors or do anything else their mind can dream up.”

The mix of people donning Polynesian ink has also diversified. “Tourism is the main industry here, and many visitors want to go home with an inked souvenir from their trip to the South Pacific,” Perez said. “I reckon that helps Polynesian culture live on and tattoo artists know that.”

From the local community, Miriama Bono, a painter and adviser to the French Polynesian culture minister, is a prominent Tahitian with a tattoo on one of her forearms, which combines motifs from Tahiti, Hawaii, Samoa, and New Zealand. Like Bono, a growing number of young Polynesians are tatting up with similarly mixed designs, nodding to the region’s broader cultural revival.

“I grew up surrounded by tattooed people, in the street, at school, in offices, everywhere,” Perez said. “I don’t have the numbers, but I’d say that easily more than half the population is tattooed.”

“Although I have almost half of my body tattooed, no one in Tahiti turns their head in the street or looks at them curiously,” he added. “It’s more like no one notices them, since it’s all too common here to have tattoos now.”