The main reason for the existence of political party symbols in India is obviously to help voters easily identify and remember the party and/or the candidate. This was even more important in the early days of the Republic of India, when the reach of literacy was limited. 1951 marked both the publishing of the first census in independent India and the commencement of the first general democratic elections. That year, the literacy rate stood at 18.33 percent, as per the census. While voting, the citizens had (and nowadays still have) before them not only the name of the candidate and the party but also the party symbol. During the campaign the electorate is reminded time and again which symbol they should choose. Some of the countless examples are: “Please vote for the Lotus” or “The Hand of the Congress is with the Common Man” (the lotus is the symbol of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, the hand is the current symbol of the Indian National Congress).

The ordeal of educating those voters that happened to be illiterate about a new symbol is well captured in the memoirs of Gayatri Devi, the queen of Jaipur. It is recalled there that those campaigning for the queen-turned-politician had to remind the electorate that the queen would be represented by a star on the election rolls. Yet, some people, seeing a symbol of a horse rider, assumed this must be the symbol of the queen, as she used to ride a horse. It was also assumed that the flower of Jaipur seen on the rolls must the queen’s symbol. Finally, upon accepting that the star is the election symbol of the queen, somebody came to a conclusion that if both a star and the sun are to be found on the rolls, the sun must mean the king and therefore the vote should be cast on both (in the first-past-the-post system in India, such vote would be invalid).

Political marketing had therefore taken deep roots in India. 1962 was a general election year in India and the February issue of a Calcutta-based daily newspaper, Sanmarg, recalled the interesting stories of candidates that had gone to great lengths to be identified with their election symbols. A man with an elephant as his election symbol campaigned on a living elephant. The animal had been taught to put the paper sheets in a box attached to it, to suggest the people they should do the same at the ballot box. A man with a tiger as his symbol went on the campaign trail accompanied by a caged tiger.

In 1957, a more unfortunate candidate had a chicken for his symbol. The would-be politician brought chicken to the voting booth where the unfortunate bird fell prey to local vultures. Hence, the Sanmarg article concludes, the candidate lost: “why would the people vote for somebody who is not even able to protect the chicken?”

Nowadays, the goals remain the same but the methods have become more sophisticated and some parties have more resources. Bahujan Samaj Party, a party based in the populous state of Uttar Pradesh in northern India and represented by the symbol of an elephant had installed numerous statues depicting this animal throughout the state. In 2012, before the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly election, the Election Commission of India came to the conclusion that the elephants may influence the voting process and had them all covered (many statues were still recognizable despite this).

As India is a secular democracy – although what “secularism” actually is and how it is understood is a subject of a different debate – the Election Commission of India stipulates that no symbol should represent a religion (or a caste). There are, however, no such rules about communist symbols and thus, for instance, the hammer and the sickle can be freely used by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The symbol of the crown is also acceptable, although it remains an enigma for me why it was chosen by a party called the Peoples’ Democratic Alliance.

Most of the parties abide by the rules of electoral secularism but some found clever ways to go around them. After all, many a symbol can easily have multiple meanings and be used by both believers and atheists. For example, Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the old party of Hindu nationalists had used an earthen lamp which is commonly associated with the ritual of the adoration of a Hindu deity, but in the party’s official interpretation, it was meant to mean progress, as this lamp was to bring light to every household of India. Similarly, Bharatiya Jana Sangh’s successor, the Bharatiya Janata Party, is using the symbol of the lotus, a sacred flower for the Hindus – but after all, it is only a flower.

The symbols are therefore subject to scrutiny from the Election Commission. A party can submit its own symbol, which the commission will consider, or choose one of the symbols suggested by the commission. This list shows how the attempt to pick official, secular and uncontroversial symbols ends up as being a list of boring everyday items. A nail cutter, a pen nib with seven rays, a plate stand or a pen stand do not seem to be the best voter magnets. Yet some of the parties have actually picked some of them. For example, the All India United Democratic Front selected the lock and the key symbol (it “probably wants to unlock all the secrets of being the numero uno party in the country,” one Internet commentator has noted).

On the other hand, even the use of those symbols can get tricky. Using the symbol of a bungalow — a building often associated with the rich and comfortable life of government officials — may be interpreted as candidly admitting one’s ultimate goal in politics. Yet in Bihar that symbol is already booked by the Lok Jan Shakti Party (“The Peoples’ Party of the Peoples’ Power”). The Samajwadi (“Socialist”) Party used the bicycle as its symbol, which has obvious connotations as a cheap mode of transport used by poor people. Therefore, I am always amused to see fluttering flags with the picture of a bicycle attached to luxurious cars used by the party’s members.

It should also be added that as the commission makes a distinction between state and national parties, the symbols can be allotted differently on these two levels: for instance, the bicycle is also a symbol of the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh (no wonder that the party eventually lost its fight in Telangana with the Telangana Rashtra Samithi which uses a car as its symbol).

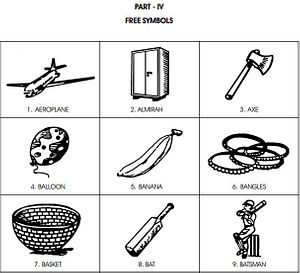

The commission’s list still offers many unreserved symbols for national/state recognized parties. If you are thinking about a political career in India, how about choosing from some of the more amusing option? How about an axe, a saw or at least a razor or pair of scissors to cut through the nonsense of your future political rivals? In a choice between a loaf bread and a cake, the former would at first seem a safer choice, if not for the fact that the bread as depicted on the list is the Western type of bread, not the common man’s chapatti. A pressure cooker would certainly keep pressure on the other parties and a neck tie will guarantee that your party will hang around in Indian politics for a longer period. As for the banana, I must admit I failed to come out with a proper interpretation.