On December 7, 2016, an ill-fated Pakistani Airlines flight from mountainous Chitral in the country’s north to the state capital, Islamabad, ended in the aircraft’s crash near Abbottabad. More than 30 perished, including 52-year old Junaid Jamshed Khan, easily one of the most recognizable personalities in Pakistan.

Junaid Jamshed’s life cannot be summarized in one sentence. He was a pop icon that later lived the life of an Islamic preacher, a Muslim Charity organizer – but also a successful businessman and fashion designer.

In the 1980s, young Junaid Jamshed had many options in life open before him. The son of an air force pilot, he dreamt of becoming a fighter pilot himself. He never did – but would touch the Pakistani sky with his popularity and, in a sad irony, eventually die in a plane crash (along with one of his two wives). Junaid studied engineering and even briefly worked for the Pakistani Air Force as an engineer but music remained a constant fascination, passion, and pull in his early life.

In the late 1980s, he was a member of a college band called Nuts and Bolts and then joined a professional pop band called Vital Sings, singing lead. The band achieved stunning success with its first album (Vital Sings 1 of 1987) and two singles, Dil Dil Pakistan (‘Pakistan in Every Heart’) and Tum Mil Gaye (‘I Met You’) stormed the hit lists. This musical success eventually persuaded Junaid to forego his engineering job and focus on singing. Vital Signs remained highly popular throughout the 1990s, but the group suffered from internal bickering in its late years, resulting in the band’s breakup in 1998. Junaid continued his musical career as a solo artist for a time, but from 1999 to 2004, he grew more interested in religion. In 2004, he turned away from his pop career and focused on religious activities.

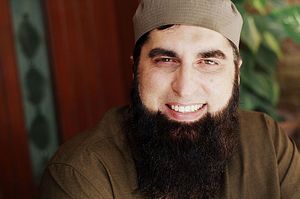

There is a sense of irony in this development when Junaid’s life is seen as a part of the broader canvas of Pakistan’s recent history. The Junaid of the 1980s and 1990s was the sweet-voiced, handsome, jeans-and-T-shirt-wearing pop icon of his generation. The Junaid of the 2000s and up to his death was a solemn, bespectacled, and bearded middle-aged man with the appearance of an Islamic preacher. Yet, the early and meteoric career of Vital Sings corresponded with the later period of General Zia ul-Haq’s dictatorship, a time of Pakistan’s politically steered Islamization. In its image and its music Vital Sings clearly followed Western trends that the Zia ul-Haq-supported mullahs were so eager to struggle with (though it must be added that the band songs were free from religious controversies and its first hit, Dil Dil Pakistan, was an anthem of pop patriotism which presumably resonated rather well in government circles).

Had Junaid chosen the path of an Islamic preacher back in the 1980s, we, both benefiting with hindsight and burdened with it, would have probably considered it a logical attempt to adapt to his times. But the artist chose this latter path in the time of another dictator-general, Pervez Musharraf, when, while the relations between the government and Islamic groups were complicated and should not be perceived lopsidedly, the official government line was not in favor of Islamization.

Once, during a long speech in Sialkot Junaid elaborated on how his growing contacts with Islamic preachers (of the Tablighi Jamaat organization) beginning in 1999 led to his final embarkation on the journey toward pure Islam. He admitted that in his early life he was not a religious person, did not pray, and was wary of activists that kept trying to drag people into mosques. But his pop star life had left him with an empty soul, he later claimed, and with the feeling of loneliness as “the role of the managers was to stop people from contacting” him. The discovery of Islam, according to him, provided the spiritual needs which he was so far lacking. Yet, the choice of starting a religious life was not an easy one as that meant ending not only his musical career, but his relationship with pop music as such.

Whether music is acceptable in Islam – and in what form – is a long debate within the Muslim tradition and there is no space and need to refer to it here (nor am I an expert in this field). But Junaid made it clear he had to quit music to fully accept Islam as the two could not reconciled in his mind. It must be noted, however, that the term he used was “mausiqi,” a derivate of English “music,” which in this context probably referred mainly to Western music and even more to Western style of modern life associated with it and thought (by Muslim preachers) to be irrevocably connected to this music.

“Whenever while playing a concert I would hear azaan [the call of prayer] I would find it an irritant,” claimed Junaid earlier in life. He also once argued that “listening to a single short song after receiving religious teachings wipes out all of them from your head.” Thus, in the early 2000s he terminated his pop music career by performing Dil Dil Pakistan publicly for the last time – at a government function and on the prime minister’s personal request, or so Junaid claimed.

From a Western perspective, one would have assumed that the two strands in his life could be reconciled, just like there are bands performing, say, Christian rock. But these would not be accepted by the Islamic clergy towards which Junaid gravitated. Yet, another perspective is also possible: whether the artist still remained tied to music depends on how we define music. Junaid used his delicate voice and skills to perform religious Islamic compositions called naats. These are considered poems (not songs) and their performance is usually called “recitation” and not “singing.” Importantly for Muslim orthodoxy, they are also performed a cappella. Yet, even a cursory survey of Junaid’s naat albums shows that they are much more singing than melodic recitation and that the choirs that accompany them form a subtle background that can be considered as skillful replacement for instruments. In other words, what Junaid was performing was still music, but of a type acceptable to Islamic clergy.

Moreover, his new life as a Muslim preacher of the Tablighi Jamaat did not mean he ceased to be a celebrity – just like with his music, Junaid was now a celebrity of a different sort. Refusing to sing even at government functions did not diminish his stature. If not for the airplane’s crash, he would have delivered a sermon at the Pakistani parliament’s mosque two days after the flight. As he once admitted, in his early years, he was recognized in a public place as “that guy that sings ‘Pakistan Pakistan’” (a clear reference to the Dil Dil Pakistan song, though the word ‘Pakistan’ is not repeated in it as such). Yet later he would have been recognized as the “the guy that sings ‘Medina Medina’” (a reference to his naat tlitled Mohammad ka Roza, where the name Medina is repeated many times).

The naats themselves were released as musical albums and some of them were accompanied by videos (albeit austere ones). Therefore, in a way his musical career continued. A few music videos show Junaid touring places such as Newcastle or London which may be read either as a part of a subtle attempt to spread the message or Islam, or an endeavor to engage with overseas Islamic audiences or – more simply – to once again underline the artist’s international fame, though he would have been expected to resist such temptations.

Moreover, the path of the preacher somehow did not collide with running a successful business venture. In 2002, already on the way to fully embracing Islam, Junaid had also become a fashion designer by starting a boutique that has grown into the J. (“Jay Dot”) company. The venture describes itself as striving to “reintroduce traditional clothes in Pakistan with a blend of modernism” and caters to the needs of the more well-off clientele (its products are nowadays found also in places like Dubai). The star later expanded his business activities to selling other commodities, including even a brand of rice. But the picture would not be full without adding that in 2003 Junaid joined the Muslim Charity organisation, hence redirecting part of his income for Pakistan’s poor (in recent years the organization also started helping Syrian refugees in Europe).

Junaid hardly ever courted controversies. One of the few times was when a video of him preaching about women’s nature surfaced in the Pakistani media. In the video Junaid is claiming that the nature of women can never be changed by giving the example of Ayesha, one of the wives of prophet Muhammad, who reportedly feigned sickness to court her husband’s attention. In yet another confirmation of the strength of Islam in both Pakistan’s and Junaid’s life, the artist was not so much attacked for a chauvinist remark, but for offending the prophet’s wife. Junaid was slapped with a blasphemy case and once even physically assaulted at an airport by religious radicals. He later offered a public apology for his words. Religion also played a role in the final event of his life – after all, Junaid went to Chitral on a mission with his religious organization, the Tablighi Jamaat.

A Pakistan grapples with the fresh tragedy of the artist’s death, the way he is being remembered varies. The religious focus mainly on the later stage of his life. The liberal, middle-class English-language media such as Dawn mainly wrote about his early musical career. This duality is well shown, for instance, in comments under articles, for example here, where one person wrote, “We should respect his decision to quit singing hence shouldn’t listen to his songs” to which another netizen responded, “So if he had quit from Tableeghi Jamat (became disillusioned from them) and simply focused on his business, would you say the same thing: We should respect his decision to quit tableeghi jamaat hence shouldn’t listen to his bayan [sermon].”

The issue of Western pop music in his early life clearly leads many to a conclusion that there were two Junaid Jamsheds, one living after the other, and what they stood for cannot be reconciled with each other. While this conclusion may be too general, it is indicative of an important cultural debate within Pakistan. Yet, regardless of this, all agree that Junaid Jamshed was a genuinely good person.