Australian politics is often characterized as brutal and bloody in a nation not often paid much attention to by the rest of the world. Books on the state of affairs have titles like The Killing Season, or Road to Ruin. All this is at the federal level, tales of perfidy from Canberra’s ambitious main players.

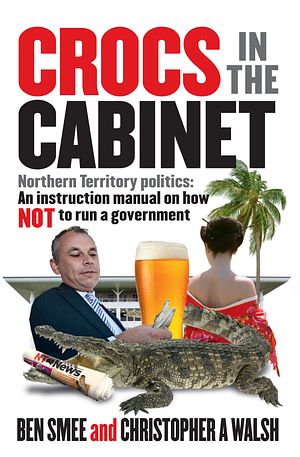

However at the state and territorial level politics have been just as confused, corrupt, or inept. A recent and valuable addition is Crocs in the Cabinet, a saga of modern day Northern Territory politics by NT News journalists Ben Smee and Christopher A. Walsh.

The back cover is as flashy, sensational, and compelling as much of the NT News. “This is Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail meets Fawlty Towers,” the cover says, and details in dot points some of the varied misdeeds of the Country Liberal Party. The party, which went from “the Northern Territory’s dominant political force to near extinction, from an election win in 2012 to holding just two seats in Parliament four years later,” is the central subject of the book. Highlights on the back cover include “A Chief Minister defying a coup by throwing his phone in a pool” and “the minister charged with assault, who sold her ‘MY HUSBAND IS HAVING AN AFFAIR WITH MY NIECE’ story to Take 5 magazine.” What sounds like a tabloid romp is actually a by turns torrid and tedious look at how to be one of the worst governments in the nation.

The journalists ably cover the dysfunction at the heart of Northern Territory politics and the demise of the once-dominant Country Liberal Party.

The Territory is geographically enormous but has a population of not much more than 100,000. It is a contrary place, as Smee and Walsh point out:

The values of the Territory and the CLP don’t make for a neat definition… people in the NT are overwhelmingly supportive of medicinal and recreational marijuana use, but at the same time rabidly opposed to harder drugs… one in five works in government and has a stake in the bloated bureaucracy, but despise the nanny state when it comes to gun control, speed limits, booze restrictions, or any attempt to stop annual fireworks free-for-all of cracker night.

Their description is reminiscent of a cable home sent by the British High Commissioner in the 1980s on Australian values. Sir John Coles wrote, “This land of ‘mateship’ and democracy has more private schools than Britain… Despite the much expressed contempt for governments this is in some ways the greatest nanny-state of all.” That contrarian nature can make for confused politics.

The authors write first-hand, as the Territory and its capital, Darwin, are small places, and they know many of their subjects. They also pad out much of the story, nearly every chapter and event, with their own clippings from the time. Whilst initially useful, the incongruity of news story after news story jammed into an otherwise chatty narrative slows things significantly. Their tabloid prowess otherwise serves them well; it is a well-written book that simply and easily explains complex local politics.

The Walkley Award-winning NT News has often caught flak for its tabloid excess and what seems like a 1:2 ratio on crocodile attack front pages. It also has some of the most legendary headlines of modern Australian journalism. However, Crocs in the Cabinet, by two of the NT News’ award-winners, goes far beyond this sensationalism into a clever breakdown of events, each another rung on a ladder heading nowhere good. Though the authors offer no wider analysis of the structures that allowed for the political shenanigans — as they admit at the beginning of the book — the problems that lead from one disaster to another are roughly the same: the CLP desperately wanted to be back in government but could not say why it should have been. Ambition decoupled from ability is toxic and futile. Vision to lead was often an individual endeavor, with the 16 ministers in the government described as “16 factions of one… at least seven of them made leaderships bids in some form or other.”

One notable example comes at the end of the book. In July last year the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Four Corners program ran an episode on the Don Dale correctional facility, where teenagers were isolated, beaten, threatened with dogs, pepper-sprayed, and placed in restraining chairs and hoods, in scenes reminiscent of the infamous Abu Ghraib prison. The reporting was so incendiary that Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced a Royal Commission the next day. The problem was not just the horrifying treatment of children, but that much of the information the program had been based on was known by ministers already. Giles, the Northern Territory’s chief minister at the time, came under fire for 2010 comments he made about being tough on all criminals. including suggesting they all be put in a hole.

Corrections Minister John Elferink, who agreed to be interviewed by Four Corners, spent his on-air time suggesting there were no issues to speak of, and offering the journalist lifts on his motorbike. The crime problem in the NT, the News wrote at the time, may have justified residents’ rage but the harsh treatment knowingly meted out to juvenile offenders simply put them on a path to reoffending. The government’s tough actions and talk was ultimately self-defeating, and damaging to the public.

The CLP wasted more time trying to govern itself — and failing — than it did running the Territory. That, and not the dysfunctional headlines, is the real story here and what makes Crocs in the Cabinet so compelling. It is, as the cover promises, a manual on exactly how not to govern. Many in Canberra might benefit from putting it on their summer reading list.