On the 26th of January, as India celebrates its 68th Republic Day, tensions are once again brewing in the Kashmir Valley and the stage is set for renewed clashes between the government, separatists, and militants. The separatist party Hurriyat has called for a statewide shutdown of activity — a bandh — and the observance of Republic Day as “black day.” The Jammu and Kashmir state government is planning to compel attendance at Republic Day festivities by students and government employees. Meanwhile, militant organizations have threatened those who participate in Republic Day activities. Once again, the average Kashmiri citizen is caught amidst competing forces with few good options.

Local reports suggest the situation in Kashmir has gotten palpably worse over the past year since the killing of Hizbul Mujahideen militant commander Burhan Wani triggered widespread unrest throughout the Valley, prompting almost four months of a government-enforced curfew. This unrest provided the backdrop for an escalation of tensions amidst militant attacks and retaliatory strikes across the line of control between India and Pakistan last September. Enduring Kashmiri disenfranchisement, growing quasi-violent political mobilization such as stone-pelting, and new sympathy for separatist tactics from even mainstream Kashmiri political elites all portend rising instability and necessitate a serious reevaluation by the Indian Republic.

Political Participation in the Valley

Despite the prevalent opinion that this recent Kashmir unrest sprung out of the blue, disenfranchisement is not new and should not be surprising. One way political legitimacy or “normalcy” is measured is through voter turnout in elections, and while turnout in the state of Jammu and Kashmir has improved over the past three decades, disaggregating voting trends reveal more alienation than “normalcy.” Based on Election Commission data, the most recent Legislative Assembly and Lok Sabha elections of 2014 generated an average turnout of 44 percent in the Kashmir Valley while the rest of the state had an average turnout of 73 percent. While other parts of the state have “recovered” their levels of political participation prior to the outbreak of insurgency, the Valley’s 2014 turnout is nowhere near the 79 percent turnout in the 1987 state elections.

The difference is not an indicator of voter apathy in the Valley but a deliberate resistance to “normal” democratic behavior. In place of voting, increasing numbers of Kashmiri residents have turned to alternative forms of political mobilization like attending the funerals of militants or stone-pelting (usually young Kashmiri men throwing stones at state police or Indian paramilitary forces deployed in the region). In the summer of 2010 when Indian soldiers killed three Kashmiri civilians in a fake encounter, there were 2,794 incidents of stone-pelting reported throughout the Valley. The killing of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani by Indian security forces on July 8, 2016 corresponded with another escalation in stone-pelting. Between July and September of 2016, a span of just three months, there were 2,330 reported incidents of stone-pelting.

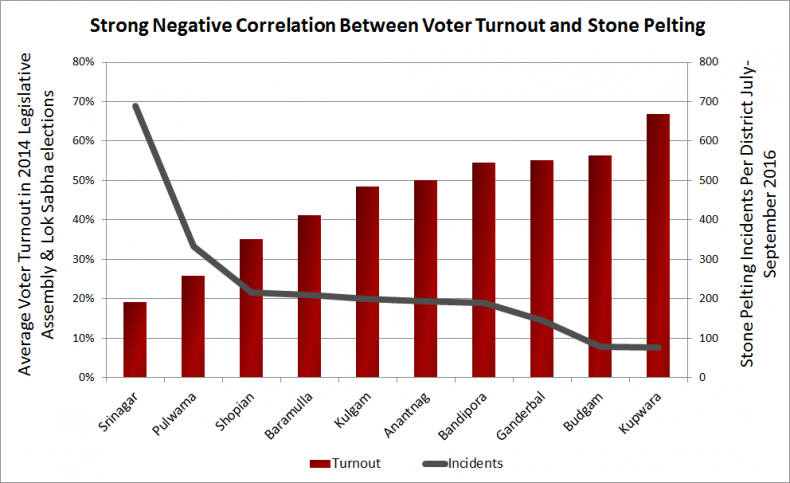

Upon closer examination of elections and political resistance activity, we find a strong negative correlation between voter participation and stone-pelting. For instance, the four districts with the lowest average voter turnout in the 2014 Legislative Assembly and Lok Sabha elections – Srinagar, Shopian, Pulwama, and Baramulla – were also home to the highest number of stone-pelting incidents just two years later. The districts with the lowest voter turnout (and presumably the highest disenfranchisement) also exhibit the highest levels of stone-pelting with a correlation coefficient of -.86 (a perfect negative correlation would be -1.0). A strong correlation held even under a variety of conditions such as accounting for population size, isolating state or national elections, and including/excluding the capital of Srinagar. In this way, unrest was somewhat predictable in the Valley. Where populations are not participating in democratic political institutions, civil unrest tends to escalate.

Source: Sameer Lalwani and Gillian Gayner

A “Crisis of Acknowledgement”

Earlier this month, senior BJP leader and former Foreign Minister Yashwant Sinha, who led fact-finding missions to the Valley last fall, published a report on the Indian state’s “crisis of acknowledgment of the Kashmir problem.” Many Kashmiris maintain that India is feigning ignorance of their grievances to avoid confronting widespread disillusionment in a productive way. The report also pointed out that antipathy toward the state, previously dismissed as an urban elite phenomenon, was even more palpable in rural areas of Kashmir. Despair has particularly taken hold among the younger generation, whose loss of faith in India’s willingness to secure their well-being has generated anger and hostility. These vast reservoirs of resentment afford local and foreign militants plenty of space to swim. Sinha’s report also warned of a dire situation in the months and years ahead. Despite the lull in political mobilization during the winter months, India needs to brace itself for renewed and more intense rounds of mobilized resistance in the spring of 2017.

Some analysts and the Indian government often attribute the suddenness of mass unrests to inordinate influence and pressures from across the border. While Pakistan has certainly played a role in the Kashmir insurgency and militant groups still operate and conduct cross-border attacks from Pakistani territory, today India’s Kashmir problem has more to do with state policy choices than external sponsorship. If Pakistan were the primary reason for simmering discontent and unrest in the region, we should expect to see greater unrest in districts closer to border infiltration nodes. This may have been the case 15 years ago, but today we see the anti-state center of gravity shifting from armed insurgency in northern Kashmir to sub-violent resistance in south Kashmir. The four southern districts combined with the heavily fortified Srinagar accounted for 70 percent of all stone-pelting in the summer/fall of 2016.

Even mainstream political elites in Kashmir who have been stalwart participants in the system are raising questions about “normal” politics. Farooq Abdullah, the former J&K chief minister and standard bearer of the mainstream National Conference party, has grown so disenchanted with Delhi he seems to have essentially backed the separatist-leaning Hurriyat party, publicly stating in December, “move ahead, we are with you.”

Health of the Republic

The strength of any republic is no greater than its weakest point. Insurgency in Kashmir has largely been militarily crushed, yet Indian policies have failed to secure a stable peace. A disenfranchised population with few opportunity costs can pose significant threats to India’s stability and reputation. And instability in this part of the world can quickly spiral into nuclear-tinged crises and conflict.

In addition to celebrations, January 26th is an opportunity for sober introspection. It is time for Indian leaders and citizens to seriously take stock of the spiraling situation in Kashmir and the recommendations of the Sinha report, not out of altruism, but for the health and security of their own republic.

Sameer Lalwani (@splalwani) is a Senior Associate and South Asia Program Deputy Director at the Stimson Center, where Gillian Gayner (@gilliangayner) is a Researcher.