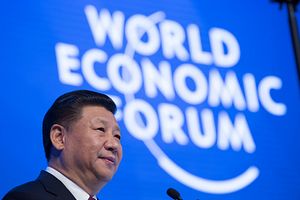

In his speech at at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, last week, Chinese President Xi Jinping cast himself as a steadfast defender of free trade, globalization, and economic openness. “We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, (and) promote trade and investment liberalization,” Xi told the annual meeting of global political and economic leaders . In essence, Xi argued that the international community needs to take steps to fix what’s wrong with free trade and economic globalization, rather than backing away from it entirely. Mend it, don’t end it, was Xi’s message.

In what was the first-ever speech by a Chinese head of state at Davos, Xi also touted China’s domestic economic picture, and plugged China’s many contributions to global economic growth.

The political motivations behind Xi’s speech are not hard to discern: at a time when global leadership is in worryingly short supply, Xi offered up China, and more specifically himself, to fill the gap. If the United States under President Trump is going to pull back from the world, Xi wanted to reassure his audience that China could step forward.

Key members of President Trump’s team certainly took notice of Xi’s speech, and they saw a contrast between the vision that Xi offered at Davos and their own perspective. Senior political adviser Steve Bannon, a lead author of Trump’s inaugural speech, was among those who cited the contrast. “I think it’d be good if people compare Xi’s speech at Davos and President Trump’s speech in his inaugural,” Bannon said in an interview with the Washington Post. “You’ll see two different world views.”

Xi’s speech set the chattering classes to chattering: was China going to take a more active role in global politics? Would Xi’s speech mark the beginning of a new era of deeper Chinese support, not just for free trade, but for the post-war liberal international system as a whole?

Any additional support that China could provide to the international system would be most welcome. Even before Donald Trump’s election, many observers were voicing concern that the liberal international order, now more than 70 years old, is showing its age. As voters in country after country elect right-wing populists who don’t bother to hide their disdain for global elites and the rules of the game that they have created, regional and global bodies like the EU and the UN have become even richer political targets. Real damage to the credibility and the stability of these institutions has been done, and there are even greater threats on the horizon. If the Chinese leadership under Xi were to make the case for a reformed liberal order – World Order 2.0, as one prominent American foreign policy scholar has called it – then perhaps Beijing’s efforts could encourage other world leaders to step forward and speak out on behalf of a system that, for all its faults, has kept the world free from large-scale conflagration for more than seven decades.

Time will tell whether Xi’s speech marks a true turning point in China’s engagement with the world. But it seems more likely that, Xi’s remarks aside, China will continue to take a cautious and reactive approach to international affairs. For decades, China has emphasized the need to respect state sovereignty, an approach which, in practice, has often shielded states from criticism for violations of international law and global norms. Too often, Beijing views international crises through the prism of its own self-interest, and as a result gives short shrift to the needs of the international community and the international system.

A closer look at China’s responses to some of the most urgent international crises of the past few years highlights Beijing’s tendency to hedge its bets, even at the cost of a more coordinated and effective international response. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, for example, Chinese officials urged respect for Ukraine’s territorial integrity, while at the same time noting that the situation involved a “complex intertwinement of historical and contemporary factors,” a vague reference to Moscow’s claims to historical rights over the territory. China then abstained from UN Security Council Resolutions condemning Russia’s incursion into Ukrainian territory, and refused to support U.S.-led efforts to impose economic sanctions against Russia.

The strategic logic behind Beijing’s seemingly contradictory moves was relatively straightforward: the Communist Party of China (CPC) leadership did not want to give its full imprimatur to Russia’s military incursion, which many Chinese international law experts viewed as a clear violation of international law, one with troubling implications for restive ethnic minority regions like Xinjiang and Tibet. At the same time, Beijing wanted to maintain or even grow valuable political and economic ties with Moscow. China’s tacit support undercut Western efforts to pressure President Vladimir Putin to pull out of Ukrainian territory. Nearly three years later, Crimea remains firmly under Russian control, and Russian interference in Ukraine’s eastern regions continues.

Beijing took a similar approach to the crisis in Syria, privileging its own interests over international efforts to end a conflict that has taken more than 400,000 lives. Since the conflict began in 2011, China has vetoed five UN Security Council Resolutions on Syria, including a 2014 resolution that would have referred the Syrian conflict to the International Criminal Court. (Russia has vetoed six such resolutions, and is generally viewed as Syria’s lead protector at the UN.) China’s Syria policy has been shaped by a number of different factors, including a desire to support Russia, which has more direct interests in play in Syria, and also a general skepticism of military interventionism – which could have eventually emerged as part of a more fully articulated international response to the civil war – on the part of Western actors. China’s feeling that it had been betrayed by the West over international intervention in Libya in 2011, which led to the downfall of the Qaddafi regime – and which China initially, grudgingly supported – also played a role.

At the end of the day, it is the United States and Europe who are primarily to blame for the international community’s failures in both Ukraine and in Syria. Without doubt, the failure to stop the bloodshed in Syria will stand as the most significant black mark on President Barack Obama’s foreign policy record. But Beijing did little to support the ultimately fruitless efforts by both the Obama administration and other actors to end one of the deadliest conflicts of the post-Cold War era.

To be sure, Beijing has, at times, helped forge consensus on key global issues. It was a leading player in the push for the December 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, for example. And China was part of the so-called P5+1 group of nations – which included China, the United States, Russia, France, the U.K., and Germany – that prodded Iran to end its pursuit of nuclear weapons under the landmark nuclear deal (formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) that was reached in July 2015. At times, Beijing has shown a real willingness to pressure North Korea on its nuclear weapons program, although that willingness seems to have declined in recent years.

In general, however, Beijing does not play a truly leading role in responding to most global hot-button issues. And it is unclear whether Beijing has the resolve, or, as a developing country facing an economic downturn, the resources, to be more active. It seems more likely that China will remain, in the apt words of one American scholar of Chinese foreign policy, a “partial power,” more active regionally than globally, and sparing in its use of political capital to address global problems that do not directly affect its own national interests.

That said, President Xi’s speech should indeed be read side-by-side with President Trump’s Inaugural Address. President Trump’s speech, with its “America First” protectionist and anti-internationalist rhetoric, was a deep disappointment. His remarks grossly mischaracterized America’s relationship with the world over the past several decades, and charted a radically different, much more self-interested and adversarial course for U.S. foreign policy in the years to come.

It may well be the case, as many fear, that America will retreat from global leadership under President Trump. For better or for worse, China will not step forward to fill the gap.

Thomas Kellogg is director of the East Asia Program at the Open Society Foundations. He is also a lecturer-in-law at Columbia Law School.