On January 20, the day President Donald Trump took the oath of office, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered his annual policy speech to the Diet. Abe pledged to strengthen the U.S.-Japan alliance, which he insisted remains the cornerstone of Japan’s foreign policy and national security. Abe is expected to meet with Trump in Washington on February 10 to persuade the new president of the indispensable role of the U.S.-Japan bilateral relationship in upholding the U.S.-led rules-based order in Asia. He will also lobby Trump on the imperatives of free trade and the strategic logic of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — from which Trump has withdrawn the United States.

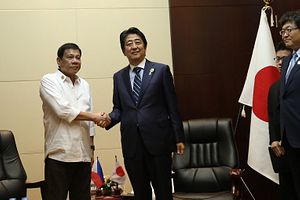

Abe’s address follows his six-day regional tour to the Philippines and Australia — two U.S. treaty allies — as well Indonesia and Vietnam in an effort to strengthen economic and security ties with its southern neighbors. Tokyo’s outreach is driven by uncertainties about Trump’s policies toward Japan and seemingly transactional approach to the U.S.-Japan security alliance on the one hand, and a resurgent and aggressive People’s Republic of China (PRC) that is challenging the regional status quo and destabilizing regional security on the other.

Minding the Gap

Under Abe’s leadership, Japan is seeking to strengthen economic and security ties with regional countries in response to an increasingly threatening external environment and proactively fill a potential gap in U.S. regional leadership and engagement. Abe’s recent trip focused on two security objectives aimed at countering the PRC’s attempts to dominate the South China Sea, through which Japan’s vital Seal Lines of Communication (SLOC) pass. First and foremost, he seeks to shore up relations and demonstrate solidarity with the Philippines and Australia — in effect reaffirming a commitment in the U.S. “hub-and-spoke” security alliance system. Secondly, Abe aims to boost the maritime security capabilities and maritime domain awareness of Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam.

On the economic front, Abe’s two basic objectives are aimed at preventing China’s growing economic dominance in Southeast Asia from displacing Japan’s regional business networks and supply chains, thereby threatening Japan’s national economic security. To this end, Abe offered a substantial 1 trillion yen ($8.66 billion) package of in aid and investment to the Philippines (See: ”How Japan Plans to Counter China in Southeast Asia”). Japan is also looking to expand investment in major infrastructure and energy projects in Indonesia as well as in the manufacturing and high-tech sectors in Vietnam. Secondly, in the wake of the TPP’s apparent demise, Abe jointly promoted free trade with his counterparts in Australia and Vietnam, which are TPP member states.

However, Washington’s categorical rejection of the TPP and single-minded emphasis on bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) means that any regional multilateral trade deals — such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — will include China as a rule-maker. In this respect, even if Washington and Tokyo are able to negotiate an FTA, it would have little restraint on Beijing’s push to shape the regional economic order. Such an outcome would indirectly undermine Japan’s efforts to build an informal regional security network to safeguard its southern approaches. Indeed, while most Southeast Asian nations look to the U.S. security alliance as a counterweight to Beijing’s hegemonic ambitions, most of these same countries have extensive and growing economic ties to China. As a result of this dichotomy between economic and security interests, most regional states (including Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam) are pursuing hedging strategies aimed at balancing their relations with the United States and China and are therefore unlikely to “align” too closely with Tokyo as a security partner.

Where Does This Leave Japan?

Abe’s regional security agenda is a welcome development within the region, but in addition to the external impediments discussed above, he faces domestic political constraints and the Japan Self Defense Force’s (JSDF) own limitations. There is widespread public acceptance of Abe’s regional strategy — though parts of Japan’s political, bureaucratic, and business classes worry about provoking China. However, handing over patrol boats and a few aircraft while holding bilateral defense talks and engaging in periodic ship visits and small-scale exercises are one thing; sending the JSDF out into harm’s way is another. Expand the regional security agenda much and Abe opens himself up to attacks by domestic opponents, claiming he is dragging Japan into military conflict with China.

The JSDF also has its own capacity constraints that hamper Abe’s regional efforts. Japan’s military hasn’t gotten significantly bigger or better funded — and won’t see much improvement in the near future. The JSDF is already hard pressed to handle existing requirements, much less start asserting itself in Southeast Asia. Under current conditions, JSDF (and the Japan Coast Guard) cannot establish a sufficient regional “footprint” to deter China, or give Japan’s neighbors to the south wherewithal to fend off Chinese coercion or the confidence to think that linking up with Japan will enable them do so.

To be clear, Japan is an exceptional ally. And, one applauds Japan and Abe taking a forward-leaning approach to regional security. This reassures friends and allies who see Japan playing a more active military role in regional affairs. However, ultimately the United States is the glue that holds together whatever informal security arrangements Japan aspires to develop.

A Japan and its JSDF closely linked to and coordinated with the United States and U.S. forces, along with their combined resources and joint efforts, is a powerful and effective check — and Chinese strategists know this. A Japan abandoned or neglected by the United States and left adrift to create a regional coalition to serve as a counterweight to China will ultimately come up short — and Japanese strategists know this. The question is whether the new and untested leadership in Washington understands the enduring strategic value of the U.S.-Japan security alliance and what is at stake if that alliance falters — the probable displacement of the regional U.S.-led rules-based order by an encroaching Sino-centric sphere of influence.

Jeremy Maxie is an Associate at Strategika Group Asia Pacific. He tweets at @jeremy_maxie. Grant Newsham is a Senior Research Fellow at the Japan Forum for Strategic Studies in Tokyo. This article has previously been published on the EastWest Institute Policy Innovation Blog.