KIEN SVAY DISTRICT, CAMBODIA — Over a narrow cement bridge spanning ponds of purple-flowering lilies lies the ethnically Vietnamese village of Koh Pos Die Edth.

With the Mekong River to its back, the village 45 minutes south of Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, sandwiched on both sides by farmland that floods at the height of the annual rainy season, consists of 40 or so modest two-story houses crowded around a bright turquoise Catholic church.

The village of Koh Pos Die Edth, surrounded by farmland, with the Mekong River behind. Image by Peter Ford.

“I want to clarify, we are not Christian, we are Catholic,” stressed 33-year-old primary school teacher Kim Sophea. Despite her Khmer name, both of Sophea’s parents are ethnically Vietnamese, and she is one of the mostly Vietnamese, 75,000-strong Catholic community living in Cambodia. The most recent census data, from in 2013, found that 0.5 percent of Cambodia’s almost 15 million population identify as Christian, rising to 1.1 percent of urban areas.

“I was born in a Cambodian village, and do actually have [Cambodian] ID, which makes life easier, and I also speak Khmer well,” she said, explaining that unlike most of the village she can find better paying work, and vote in the upcoming local and national elections.

“I feel Cambodian, but living in this community, I also feel Vietnamese.”

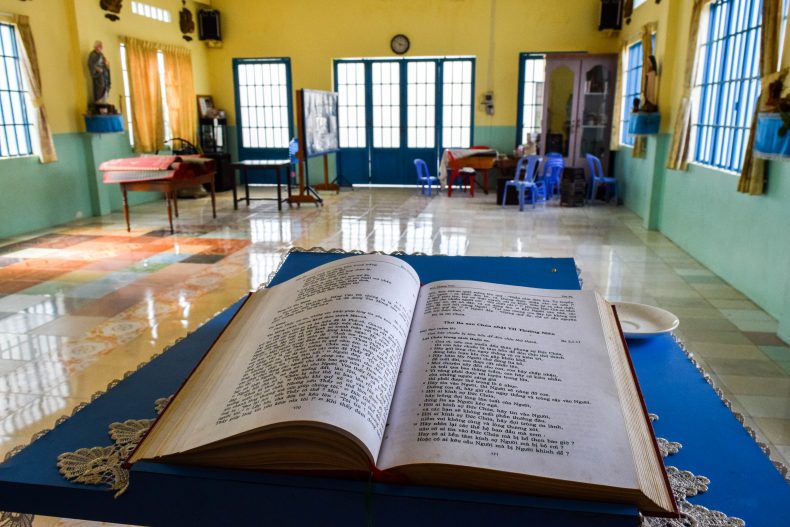

Posters visible through house windows, the bible in the church, even the graffiti, is all in Vietnamese.

The writing on the wall, in Vietnamese, announces that the play of football is banned near the church and school. Image by Peter Ford.

“Before we were all fishermen, but now we cannot make a living from this as the fish have gone. The men do odd jobs such as making keys and laboring, while many of the women collect recycling. We are surrounded by Cambodian-owned farms as we don’t have any land. We could rent, I suppose, but no one knows how to farm.”

Danger

The recent history of Vietnamese living in Cambodia is often painful.

French colonial influence between 1867 and 1953 brought with it the first major arrivals of Vietnamese into the country, in the form of local administrators and rubber plantation supervisors.

Portuguese Catholic missionary efforts in 1555 had been unsuccessful in Cambodia, but had fared better in Vietnam. With French support, the Catholic church’s status grew in Cambodia, culminating in the completion of the Notre Dame Cathedral in 1962 — destroyed by the Khmer Rouge in 1976.

With a mostly Vietnamese congregation, however, the situation for Cambodia’s Vietnamese population, and by extension, its Catholic residents, became more tenuous following independence.

The houses in the village are simply-made from brick, cement and metal sheeting, and lack the distinctive spirit houses found outside Buddhist houses in Cambodia. Image by Peter Ford.

In 1970, General Lon Nol orchestrated a coup against the then Prince Norodom Sihanouk, whose increasingly anti-Vietnamese policies were further intensified. Pogroms, mass expulsions, and killings took place across Cambodia, and many Vietnamese were forced to flee south. On April 13, some 800 Vietnamese men were gunned down and by the end of the year, an estimated 7,000 Vietnamese Catholics were still living in Cambodia, down from 65,000 a year before.

“My whole family was chased away by the authorities. I don’t know the reason why, but I was scared,” remembered Sophea’s mother, Nguyen Yi Can, who was 16 at the time.

Born near Wat Krosar, on the banks of the Mekong somewhere near her present home — she can’t remember its exact location — she returned in 1982, four years after the Vietnamese army had entered Cambodia and quickly overthrown the Khmer Rouge government.

The Khmer Rouge’s own attitude toward the Vietnamese in Cambodia, and their actions against them (despite owing much of their early funding and training to Vietnamese comrades), has seen charges of genocide brought against the two most senior surviving leaders, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.

Not confident in her Khmer language skills, Nguyen deferred further questions to her daughter.

“We used to live close to the river behind the brick factory over there,” Sophea said, gesturing to a lone brick tower a kilometer south of the village.

“The owner let us live rent free but about 10 years ago the owner changed, and we had to move as we couldn’t afford rent.”

A Vietnamese Catholic priest living the United States, whose name she could not remember, bought this small piece of land for the community in 2005, and was instrumental in building the church in 2014.

Officially named “The Lamb of God Factory Church,” in relation to the community’s former location next to the brick factory, locals usually just refer to it as the factory church.

“In 2005 there were about 40 families, now it is 70 I think… and most attend the church, normally about 100 each Sunday, and 30 come from around the area.”

“On big celebrations up to 400 people attend, coming from across Cambodia and also from Vietnam,” she said with pride.

School teacher Kim Sophea standing in front of the church with some of her students. Sophea is also volunteer caretaker of the church. Image by Peter Ford.

Barriers

Villagers are poor but hardworking, she said, and while they get on well with their Khmer neighbors, a lack of Khmer language skills among the Vietnamese community has direct negative effects.

“The older people do not speak much Khmer, some even none at all, and so they cannot find work outside of our community.”

The 2013 inter-census found that 0.42 percent of people in Cambodia speak Vietnamese as their mother tongue.

For the village’s children, however, parents and community leaders stress the need to learn the national language, going so far as to enforce a “Khmer only” language policy in school lessons.

This emphasis on the importance of learning Khmer has also spread into the naming of children born in the community.

“It is funny how the Catholics in Vietnam all use Western names, but here many choose to take Khmer ones instead to help them integrate.”

Church services take place each Sunday at 8 a.m., and feature about 130 families from the village and surrounds. Everything takes place in Vietnamese. Image by Peter Ford.

There is only so much that the community can do though, as ethnically Vietnamese children are not awarded birth certificates, and can therefore only access public schools until grade 5.

Despite this, Sophea insisted that relations with the local Khmer population are good.

“Things have gotten better in the last 10 years. No one has been deported from here, but in the Champa area about 7 km away, there have been some deportations. That community is even older than ours, but they don’t have any way to prove it.”

Of the almost 3,000 people deported from Cambodia in 2016, the vast majority were Vietnamese.

“When people are deported, they get no support from Vietnam and have no relatives there, so most make their way back to Cambodia. This is where they were born. People are scared, but our leaders have good relationships with the local authorities and so we get informed about possible raids and we get on well with everyone.”

Harvest

Around the village, the cauliflower harvest is in full swing, with each farm collecting some 2,500 kg, and the fields are full of Khmer villagers.

“We all get on well. Just don’t call them ‘yuon’; they don’t like it,” said one, declining to give her name.

The term, while being the Khmer word for Vietnam and Vietnamese, in recent years has taken on a more derogatory connotation. Its frequent use by members of the opposition has drawn criticism for perceived racist overtones, prompting former Cambodian National Rescue Party leader Sam Rainsy to defend his continued use.

The specter of possible deportation due to not having legal residency status means that Vietnamese communities are close knit by necessity, a fact not lost on the village’s Khmer neighbors.

“I appreciate how they support each other as a community, much better than we do,” said Mao Long, who has lived all of his 50-something years in the community.

“I don’t speak any Vietnamese, but we are not mean to them, I have many friends from here and we often drink rice wine together, and they make good food,” he said laughing.

Farmer Mao Long has lived nearby his whole life, and often eats and drinks with friends in the Vietnamese community. Image by Peter Ford.

He grows tomatoes, beans, and cauliflower on the land within sight of the church.

With Cambodia importing up to 400 tons of vegetables daily from its southern neighbor, locally grown produce fetches a premium price.

“Most people like to know their vegetables are grown here in Cambodia,” Long explained.

“And didn’t come from Vietnam.”

Additional reporting by Thavry Thon.

Peter Ford is a freelance journalist based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Follow him on Twitter @PeteAFord