May 2017 marks the one-year anniversary of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s landmark trip to Iran, where he applauded the signing of a regional connectivity agreement centered around Iran’s Chabahar port as the “creation of history.” India’s willingness to make a major strategic play for Central Asian trade is remarkable, but major areas of the plan remain to be fleshed out — most importantly the question of the port’s economic viability, even in a best-case scenario. The likelihood remains that Chabahar will be more of a strategically impactful venture than it is an economic one.

When India, Iran, and Afghanistan signed a trilateral agreement to develop a transport corridor from Chabahar through Afghanistan, it marked the culmination of over a decade of Indian hopes for an alternate land route to Central Asia. The deal depends on Indian state investment: state-owned India Ports Global Private Limited (IPGPL) is responsible for expanding the port itself to bring capacity to 12 million tons per year; India’s EXIM Bank has offered a $500 million line of credit to fund work on rail connections to the port; and Ircon International, another public-sector undertaking, will build a $1.6 billion railroad from Chabahar north to Zahedan on the Iran/Afghanistan border. Zahedan in turn is a node on the Iranian rail network, which connects to Turkmenistan and eventually to Kazakhstan’s Caspian seacoast. It also provides convenient access to the start of the Indian-built Zaranj-Delaram highway, which intersects with the Afghanistan ring road. Despite the occasional hiccup, work on developing Chabahar appears to be progressing: IPGPL is selecting a private contractor to carry out construction.

The plan to anchor new trade routes to Central Asia with a deep-water port at Chabahar has been frequently described as a riposte to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and its Chinese-sponsored port at Gwadar. For India, it is a chance to position itself as a player amidst the land corridor mania that has gripped mainland Asia and to stake its claim as Afghanistan’s primary economic partner. Unsurprisingly, however, the Indian government has sold the plan not as a primarily strategic venture but as an economic one that will promote the “unhindered flow of commerce” between India and Central Asia.

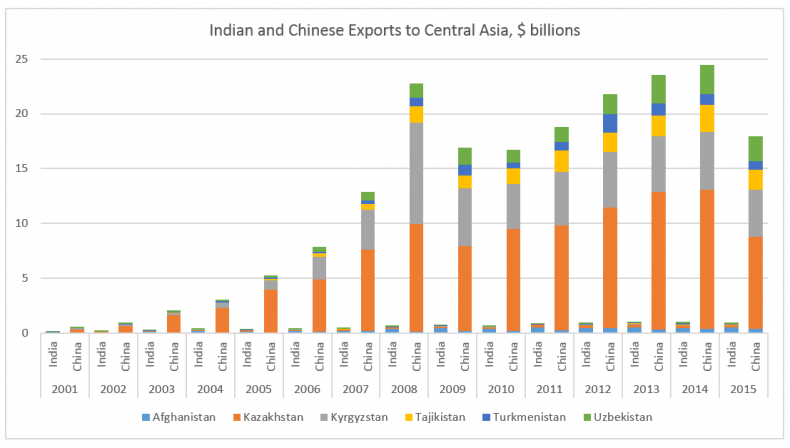

The statistics on China and India’s exports to Central Asia (Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) makes clear the promise and limitations of the project. In 2001, China exported half a billion dollars worth of goods to Central Asia, while India exported $100 million. By 2015, however, China exported nearly $18 billion to the region, while India exported only $950 million. China currently exports nearly twice as much to tiny Tajikistan as India does to the entire region.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Statistical Database, http://unctadstat.unctad.org

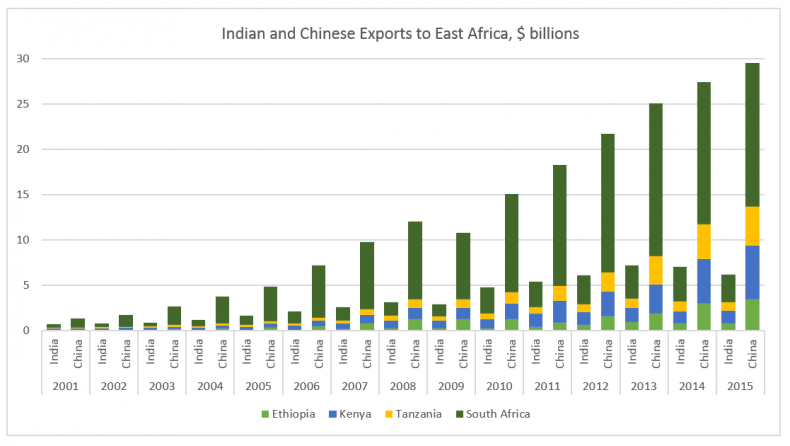

This imbalance suggests an obvious rationale for increasing India’s connectivity to Central Asia. Delhi is only about 1,000 miles from Almaty as the crow flies, compared to 2,500 miles for China’s eastern manufacturing hubs. Chinese goods, however, can travel by rail to Kazakhstan and then take advantage of road access to most of the region, while India’s land route to Central Asia is blocked by unreliable access through Pakistan. Despite the hurdles India faces when exporting to the region, its trade with Central Asia has grown steadily; its exports to Afghanistan, in particular, have increased more than 25 times since 2001. These data suggest that with improved connectivity India’s exports could see more explosive growth. But it’s important to note that Indian exports are still dwarfed by China’s even in regions where it has far better connectivity. Despite its relative proximity to East Africa, for instance, Indian non-fuel exports to four of that region’s largest economies were less than a quarter of China’s in 2015.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Statistical Database, http://unctadstat.unctad.org

In his speech announcing the project, Modi said that the land route to Europe via Chabahar “could bring down the cost and time of the cargo trade to Europe by about 50 [percent]” compared to the price of sea transport. This is a surprising statistic given that freight charges for maritime shipping are about 60 percent of those for rail freight: for instance, it currently costs about $1,500 to ship a 40 foot container from Shanghai to Europe by sea (sometimes falling as low as $200), versus $2,500 to go by rail, even though the overland route is much shorter.

A 2014 report by the Federation of Freight Forwarders’ Associations of India (FFFAI) in conjunction with the Indian government’s Ministry of Commerce reveals the thorny logistical challenges involved in a sea-land route to Central Asia via Iran. The FFFAI conducted a dry run for the proposed “International North South Transport Corridor,” shepherding 20 foot containers along two test routes, both originating in Mumbai; one terminated in Baku, Azerbaijan and the other in Astrakhan, Russia. The Mumbai-Baku route cost $3,132 and took 33 days from “door to door”; the Mumbai-Astrakhan route cost $3,339 and took 43 days. By way of comparison, a container ship can make the journey from Mumbai to Rotterdam in 26 days, although additional time must be allowed for administrative processes at both ends. Even when the overland route is completely streamlined, it is unlikely to bring goods to European markets faster than the sea routes.

Both routes used in FFFAI’s experiment passed through the existing Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, located less than 300 miles from Chabahar in the Strait of Hormuz. Bandar Abbas, Iran’s largest port, already has direct rail connectivity to Turkmenistan and from there to Kazakhstan. In contrast, even when the Chabahar-Zahedan rail link is completed, goods bound for Central Asia will have to travel farther west to join the main rail line to Mashhad. This makes Bandar Abbas an obvious first choice for rail shipment north. (In fact, goods are currently more likely to travel north via road, but this makes the logistics of an India-Europe rail corridor even more complex.)

Furthermore, multiple passages in the FFFAI report emphasize the importance of volume to decrease shipping charges and time on the India-Iran-Central Asia routes; for instance, currently ships departing Mumbai for Bandar Abbas generally stop in Dubai or at the Gujarati port of Mundra in order to load enough cargo to make the trip economically viable. Greater volume would also allow the Iranian railways to charge a far lower tariff to bring cargo from Bandar Abbas to transshipment points in Northern Iran. The need for volume on what are still nascent trade routes is a strong argument against promoting an alternative port for Indian trade to Iran. This is especially so given that that FFFAI estimated non-agricultural trade along the India-Iran route would be worth only $150 million per year. In the short-term, at least, the Indian government may need to offer subsidies to grow volume on both routes and to create the efficiencies of scale that will make them economically viable.

Chabahar’s principal attraction over Bandar Abbas appears to be its relative proximity to Afghanistan, especially once the Chabahar-Zahedan railroad is complete. Afghanistan is the one country in the region where India beats China in terms of exports, despite the unreliability of passage through Pakistan; the Indian and Afghan governments are anxious to build closer economic ties. But trade with Afghanistan presents numerous complications beyond the simple movement of goods.

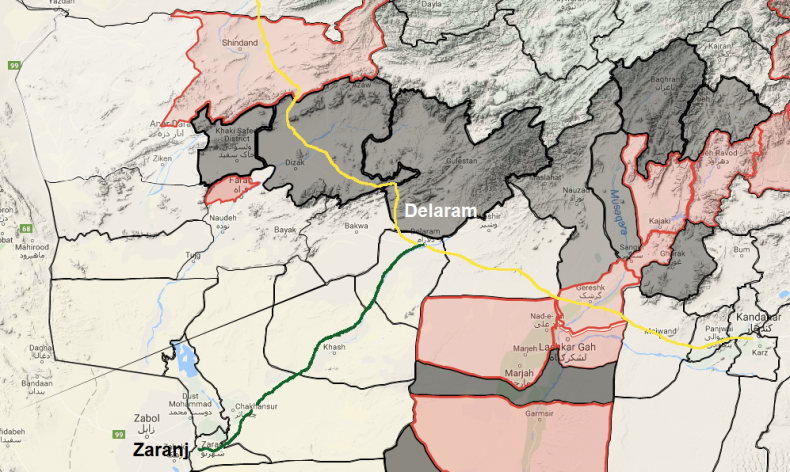

Kabul has apparently already warned India that the Taliban could attack trucks carrying Indian exports. This warning is given force by the fact that the Taliban control or contest most of the districts to the east or west of Delaram, the terminus of the Indian-built highway from Iran. Thus Indian goods traveling to Kabul or Herat will have to pass through, or close to, some of the most dangerous parts of the country. Although it is to be hoped that increased trade will eventually help improve Afghanistan’s security situation, the persistence of Afghan insecurity likely makes Chabahar a very long-term play for India.

Source: Long War Journal/Foundation for Defense of Democracies, “Map of Taliban controlled and contested districts in Afghanistan,” updated March 1, 2017. The green line shows the Zaranj-Delaram highway and the yellow line the ring road.

The close bilateral cooperation that infrastructure development requires also threatens to drawn India into the morass of Iran-Afghanistan politics — just as China’s investment in CPEC inevitably involves it in Pakistani internal politics. Iran’s longstanding support for the Afghan Taliban appears to have increased in recent years. Since at least 2015, media reports have indicated that Iran provides factions of the Afghan Taliban with money and materiel. Under President Hamid Karzai, who reportedly received large cash payments from Iran, the Afghan government was largely silent on Iran’s role in the conflict. While Afghanistan still seeks a constructive relationship with Iran, the Afghan senate announced early this year that it would investigate Iran’s ties to the Taliban. So far India has benefited from the diplomatic cover provided by Afghanistan’s support for the Chabahar initiative, but if Afghan-Iran ties worsen India may be forced to pick a side.

Engagement over Chabahar could also bring India and Iran closer just as Iran and the United States are on a new collision course in Afghanistan. The U.S. position has so far remained muted, but a change of administration could increase U.S. willingness to make Iran’s involvement in Afghanistan a major geopolitical issue. In 2012, General John Allen, then leader of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, told Congress that Iran was supporting the insurgency but that it “could do more if [it] chose to.” In late 2016, by contrast, General John Nicholson mentioned Iran in the same breath as Pakistan when discussing the “malign influence” of external actors in Afghanistan. In February, he testified to Congress that Iran was supporting the Taliban. The Trump administration, including a secretary of defense who is a well-known hawk on Iran, is likely less inclined than its predecessor to play down Iran’s support for the Taliban, especially given the possibility that the United States will increase troop strength in Afghanistan.

More than two years since Modi declared that his government had converted the previous “Look East” policy into an “Act East” policy, his regional connectivity agenda in India’s east has largely stalled. India’s desire for better connectivity to its Central Asian backyard is understandable. But Chabahar will involve India more deeply in the murky waters of continental Asian politics. Without a clear economic rationale, it could prove a dangerous distraction from more important efforts.

Sarah Watson is an associate fellow in the Wadhwani Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).