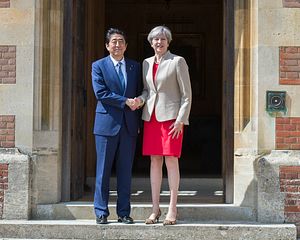

This past week saw a cordial meeting between Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and British Prime Minister Theresa May at her official country residence, Chequers. Two concerns dominated the meeting: The U.K.’s Brexit strategy and the implications for Japan and the escalating tensions surrounding North Korea.

For May, the meeting provided an opportunity, prior to June’s General Election and ahead of the Brexit negotiations, to demonstrate to her domestic audience as well as to the EU the potential for Britain to negotiate bilateral trade agreements should this prove necessary, and to assure Japan of British efforts to continue to prioritize trade post-Brexit. For Abe, the primary Brexit concern is the possible impact on the exports of the roughly 1,000 Japanese firms with operations in the U.K. after Britain leaves the EU on or around March 2019. The fear is, of course, what future tariffs, if any, may be imposed on U.K. exports to the EU.

There are three possible Brexit trade outcomes. The first scenario is that the U.K. and the EU agree that Britain stays in the single market customs union, even though it ceases to be a member state. This is not necessarily impossible. Norway, for example, whose electorate remains strongly opposed to membership in the EU, is a member of the single market and trades without tariffs just like any other EU member state. However, such a “business as usual” trading arrangement for the U.K., without any detrimental economic impact, seems hard to achieve. For London, allowing free movement of EU citizens into the U.K., a demand of the EU, likely represents a negotiation red line.

A second outcome might be that the U.K. and the EU agree a trade deal whereby the U.K. leaves the single market, but is able to trade with the EU on preferential terms compared to those nations outside of the customs union. This outcome would limit any negative economic impact, leave the U.K. free to negotiate its own trade deals, and would be reassuring to foreign firms in the U.K.

The third possibility is that the U.K. and EU simply prove unable to reach an agreement, leaving the U.K. to trade with the EU under WTO rules and tariffs. Although this would also leave Britain free to negotiate its own bilateral trade deals, the economic impact would be more substantial and, in extremis, might lead foreign firms to leave the U.K.

May understands that Brexit represents an economic risk. While Japanese auto manufacturers, for example, may not experience problems in manufacturing cars in the U.K. and selling them to the British post-Brexit, they may be forced to pay tariffs on their British-made cars if exported into the EU. May’s challenge, therefore, is to reassure Britain’s major trading partners, including Japan, that London’s prospects post-Brexit are not overly negative, and that she is working to limit any damage. A meeting like the one with Abe is an opportunity for her to do just that.

While giving some comfort to Japanese firms, both parties know this only provides partial reassurance. After all, only the U.K. and the EU-27 can decide their parting terms. Considering the costs involved, it seems unlikely Japanese companies will make any hasty decision to exit the U.K. Rather, they will probably adopt a “wait and see” approach over the next two to three years as Brexit process and its trade impact unfolds.

Abe, for his part, stated his “continuing confidence in the economy of the U.K. after Brexit,” a message that May was no doubt happy to receive. For Abe, the opportunity to present himself as a business-focused leader was surely positive in the face of lackluster domestic economic growth and political scandals at home.

The second critical matter the leaders discussed was the deteriorating North Korea situation, a national security issue for Japan given its proximity to that nation. North Korea seems committed to the development of long-range missile systems and miniaturized nuclear warheads, which can be mounted to such delivery systems. If these technical feats are mastered, the potential exists not only for North Korea to threaten Japan but also, ultimately, the west coast of America.

May lauded Japan as the U.K.’s “closest Asian security partner” and condemned North Korea for its “destabilizing activity” and “belligerence,” representing a “risk to global peace and stability.” Words alone, however, are unlikely to stop the North Korean leadership from pursuing its military ambitions.

Hours after May-Abe meeting, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said at a special meeting at the United Nations in New York, “We will not negotiate our way back to the negotiating table with North Korea; we will not reward their bad behavior with talks.” He suggested additionally responding with sanctions and international isolation, even though similar measures proved to be largely ineffective in the past. North Korea showed its as-yet-undiminished resolve by conducting a further, albeit unsuccessful, missile test only hours after Tillerson’s speech. While there are some calls for a resumption of the Six-Party Talks, the key issue seems to be the lack of any meaningful international consensus or diplomatic strategy in terms of how best to move forward.

The outlook appears increasingly risky and dangerous. And any solution will no doubt prove to be a lengthy endeavor. Nevertheless, positive meetings in the manner of the recent May-Abe talks, particularly with nations such as the U.K. that maintain diplomatic relations with Pyongyang, may at least help in the search for a coherent response to defuse this seemingly intractable crisis.

Yukari Easton is a researcher and an ACE-Nikaido Fellow at the East Asian Studies Center at the University of Southern California, with a research focus on international relations, diplomacy and security issues in the Asia-Pacific region.