If the People’s Republic of China were a multi-party democracy, in which different politicians had to compete for power, at about this time the campaign trail would start to heat up. We are a mere six months at most away from when seeing either current leaders reappointed or new ones emerge. This being China, however, with a Communist Party still enjoying a monopoly on power, there is nothing as unseemly as a scramble between different figures. All we will observe over the coming months are the few sporadic signs of activity under the surface, while in a hundred different rooms and places, far away from sight, decisions are being made. The hidden horse-trading will culminate when the Standing Committee of the new Politburo walks out, sometime in October or November.

In democracies, campaigns almost always involve evaluations. Have the incumbents done enough to merit re-election? Have they kept their promises? If they haven’t, what are the reasons for that? Does the electorate feel happy, or angry, or let down? Who else is standing who is worth trusting? Candidates in power invariably produce their list of achievements – economic growth, jobs created, peace deals signed, trade deals completed. The general rule (there are many exceptions, of course) is that a party in power will stand a much better chance of being elected back in if it does so on the basis of solid economic growth. Electorates on the whole are risk averse. Unless pushed by frustration or anger, they tend to stick with the bunch they know rather than people who are untested and new.

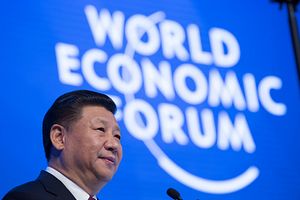

Were Xi Jinping having to defend himself for re-election against a hypothetical opponent, where would he and his administration be vulnerable, and where would he be on solid ground? If he were on the stump now, presenting his case through televised debates to the Chinese people, what sort of questions would be flung at him, and how would he be able to respond?

On the economic front, this administration would be solid, but not spectacular. An opponent would be able to say that Xi and company started with growth above 8 percent, and that since 2012 it has been on a downward slide. Xi would be able to point out the reasons for this – changes in the composition of the Chinese economy, the global situation, etc. But it will still be a point worth attacking.

An opponent would also look at the many promises made under Xi – the 60 or so in the Third Plenum Communique issued in 2013. They would ask how many of these, from cleaning up the environment to delivering better social welfare and relaxing the one child policy, have been implemented. Here the picture would also be murky. The one child policy has indeed been scrapped. Complex fiscal reforms have allowed more decision making power to go from the center down to provinces. But the environment is still in a parlous state, despite the very real achievement of signing the Paris Climate Change Convention in 2015. Many of the grand promises to forge ahead with reform from 2013 onward are either incomplete, or have yet to even start. An opponent would raise the question in the electorate’s mind of whether this administration is all talk and little do.

Xi might point to his success in raising China’s profile abroad, through his various global travels. He might point to the meeting with former President Ma Ying-jeou of Taiwan in Singapore in late 2015. But the issues in the South China Seas and over Taiwan are nowhere nearer resolution today than they were in 2012 when Xi came to power. At best, the status quo has been preserved. This is hardly an exciting message to give the electorate. In any case, democracies usually show that people tend to judge their leaders on domestic issues, not international ones. They are just a subsidiary.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan, during his first campaign to be president in 1980, attacked then-incumbent Jimmy Carter by asking the American people, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” Most felt they were worse off; Reagan was elected. If an opponent said the same thing in Xi’s China, what would the answer for most people be? How have their lives improved since 2012, in the era of the Belt and Road initiative, the China Dream, and the anti-corruption struggle. Do they feel they are better or worse off?

Of course, China is a huge, diverse, and complex society. People will have responses across a huge spectrum on this question. But broadly, despite the aspersions of Xi’s immense power, the answer for many is unlikely to be a resounding yes. Their living costs have continued rising. House prices are as high in some cities as in Sydney or London. Those in early adulthood still need to live with their parents because of the staggering costs of real estate. In cities, air quality and water and food safety are still poor. Roads remain clogged with cars. Wages have risen, but not as high as some would want. Growth has become slower and tighter. The era of breakneck wealth creation of the early 2000s is over. That has a dampening effect on national sentiment.

Chinese people today, compared to 2012, probably feel that the Party officials they deal with have become more responsive and the Party itself is not as mired in collusion and embezzlement as it was in the era of Hu. The anti-corruption struggle has, presentationally at least, lifted the image of the Party. But they would still fear falling ill because of the expense, and the highly uneven quality of service, of the Chinese healthcare system. And they would not be relaxed about the day when they retire because of the very uneven provision of pensions. And many would still feel anger that there are such massive wealth differences in a supposedly socialist country.

In this context, how would Xi pitch his campaign? The domestic and international achievements are solid, but not spectacular. He might ask for more time to carry through on his reforms. In democracies, leaders often use that tactic. But it is more likely that he will use the “better the devil you know” theme. In any final televised presidential candidate debate, he would be able to look in the camera, addressing the Chinese people directly, and say, “We are the Party that will get this country to its dream of being a middle-income, respected, modernized economy, a place where our children can go around the world and be proud, not embarrassed, to say they are Chinese.” As in all elections, he would appeal to people’s emotions, not their heads. It would be on this, and this basis alone, that he would seek his second term. And it is likely that with this sort of message, even in a multi party democracy, he would stand a good chance of winning.