Following decades of saber-rattling, recent events on the Korean peninsula appear to have the United States and North Korea on a collision course. As potential conflict on the peninsula approaches, observers are fixated on the possible doomsday conventional military clash between North Korea and U.S. forces. Such a military clash has long captured the imagination of senior military officials as an apocalyptic conflict ushering in untold destruction. While it is tempting to view potential war in Korea as a test of conventional military might, the United States must focus its planning not only on defeating North Korean forces on the battlefield, but more importantly on securing the peace in postwar northern Korea. If U.S. forces find themselves standing in Pyongyang having vanquished the Cold War-era military of a failed regime, just like in Iraq, the real fight is likely to have just begun.

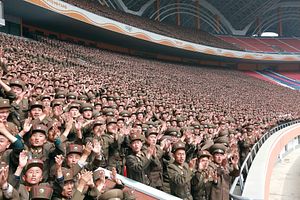

The Kim regime likely realizes it cannot win a conventional war with U.S. or South Korean forces. However, it remains determined not to go gently into that good night. Publicly available intelligence indicates that the regime watched with interest as allied forces rolled over Iraqi conventional military forces only to become bogged down in a military quagmire afterwards. Having observed the U.S. quandaries in the Middle East, North Korean forces are already training in insurgent tactics such as roadside bombs. Austin Long, a leading scholar on counterinsurgency and international affairs, recently suggested North Korea is ripe for a vibrant insurgency following any collapse of the Kim regime. In short, the greatest impediment to a peaceful and unified Korea may not be the North Korean military seen goose-stepping on television, but rather a vibrant postwar insurgency.

While planning for any conventional war on the peninsula is critical, allied forces must avoid repeating the mistakes of history. In Iraq, military planners focused on military strategy at the expense of providing basic infrastructure and rule of law to indigenous peoples. This error allowed an insurgency to take root that proved more deadly to allied forces than any conventional Iraqi force.

Similarly, the population of North Korea will not greet U.S. and South Korean forces as liberators. It would be a grave error to assume that North Koreans will simply be overwhelmed with joy at having food, iPhones, and K-pop. Much like in post-war Iraq, the vacuum created by the loss of an authoritarian regime cannot simply be filled with platitudes of freedom and liberty. Further, it is likely China will covertly, or even overtly, fuel insurgent forces in the region. The prospect of pacifying a brainwashed population of 25 million, while Chinese forces meddle, should be far more frightening to military planners than subduing a North Korean military that still employs Cold War technology. For this reason it is imperative that a Korea-specific counterinsurgency plan be in place prior to any conflict or regime collapse.

Successful counterinsurgency requires a rule of law that the populace deems legitimate. The rule of law is the legal system that will be enforced on North Korea immediately following the collapse of the Kim regime. Counterinsurgency experts suggest that the rule of law is given its credibility and power through its ability to connect with social norms. In other words, indigenous groups must feel an innate cultural and moral connection to the rule of law. When the local population feels a legitimate connection to the rule of law, there is less dissatisfaction from which insurgent groups can draw support. Indeed, the U.S. experience in the Middle East has led to a new understanding that the effective use of the rule of law is a counterinsurgency warfighting tool. In the context of the Korean peninsula, in order to pacify the northern population, the unified Korean government must be seen as a more legitimate source of authority than any insurgent movement.

In this context, for any rule of law to be respected in northern Korea, it must be true to the legal traditions of the indigenous people. Simply enacting a Western rule of law, or even South Korea’s modern and capitalistic legal system, would result in chaos. The people of North Korea, intellectually imprisoned for decades, will not be prepared to accept any such rule of law as legitimate. The resistance to a more Western rule of law that the United States faced in Iraq and Afghanistan will seem minor when compared to the reaction of a brainwashed population to an alien legal system.

I propose two key concepts be embraced as senior leaders envision a rule of law in unified Korea. Firstly, any rule of law must be Confucian in nature. Secondly, the packaging and enforcement of that rule of law must utilize the North Korean theme of juche. By enacting a traditional Confucian-style legal system and utilizing juche principles in its enforcement, the people of northern Korea will feel an innate connection toward the rule of law, thereby granting it legitimacy and ensuring a more peaceful unified Korea.

A Confucian Rule of Law in Post-War Korea

Named after the Chinese philosopher Confucius, Confucianism has a long and rich history in Korea. Confucianism went beyond serving as a philosophy or religion in Korea; rather, it actually served as the foundation of legal thought. The Confucian legal tradition in Korea stretches back to the 2nd century BCE. Prior to Japanese occupation, for hundreds of years Korea utilized canons of law that reflected the broader Confucian principles of Korean society.

Confucian-based law stresses the collective over the individual, the importance of finding harmony in society, and the value of the family culture. Contrast these values with Western societies, which emphasize individual rights and personal responsibility. Transplanting Western notions of how a judicial system and code should look into postwar northern Korea would be met with disastrous results as the North Koreans reject concepts foreign to them. Rather, allied forces must enact a rule of law based on Confucian principles familiar to the history of northern Koreans.

As a general matter, the idea of what I term “village justice” is strongly embedded in Confucian tradition. Confucian thinking discourages centralized legal systems whereby litigation is given free reign. Rather, a harmonious solution is one reached through consensus by old and wise elders. Indeed, in Confucius’ teachings, he described the harmonious society as one that eliminates litigation. This teaching is evidenced in other traditional Confucian societies, such as China. In such traditional societies, individuals “settle their difficulties not by going to court but by holding a community council to settle disputes, chiefly on moral considerations… [l]aw is not of much use in villages.”

An analogy can be drawn to the U.S. experience in Afghanistan and Iraq. After years of conflict, U.S. forces determined that working with decentralized authorities, such as village elders, was far more effective than sweeping federal reforms. Similarly, the rule of law in northern Korea must be decentralized in nature. Reliance on village justice has its drawbacks. For instance, women’s rights may not be given a priority. However, stability will be ensured and, ultimately such important issues as women’s rights will more rapidly progress due to a stable and open unified government.

Any rule of law enacted in post-war northern Korea must emphasize the importance of traditional Confucian filial piety. Family loyalty is an incredibly powerful concept in Confucian culture. Any law enacted should grant special protections for family members and codify criminal sanctions for lack any of filial piety. For instance, China codified an “Elderly Rights Law” under which parents have the right to request mediation, or even file a lawsuit, against children who do not properly care for them. Confucian tradition states that “Fathers cover up for their sons and sons cover up for their fathers. Uprightness is to be found in such behavior.” The law should carve out special protections for family relationships, such as never requiring one family member to be a witness against another.

Traditional Confucian familial ideas, which remain in effect in North Korea, may seem rather outdated in the Western mind. However, when establishing legitimacy in northern Korea, they hold tremendous power. For instance, notions such as a prescribed three-year mourning period for the death of one’s father, no matter how alien and unfair such a legal requirement may seem, should be embraced. It is arguable “that Confucianism emphasizes filial piety to the neglect of social welfare.” However, despite any alleged societal cost of implementing a legal system that enacts traditional Confucian filial piety, such a rule of law will pay incredible dividends in the long run as the indigenous population begins to support the unified government.

Most importantly, it is vital that allied forces do not blindly enact a rule of law that is adulated in the West while it is anathema to North Koreans. The principles of equality and individual freedoms are cornerstones of Western thought. However, such concepts will be foreign and not recognized as legitimate to the people of northern Korea. The historical philosophy of Confucianism, while championing justice, emphasizes different values. For instance, the right to remain silent is traditional to Western thought, not Confucian. Framers of the rule of law should consider not including such cornerstones of Western thought. Due to the cultural isolation of North Korea, such concepts may ring hollow in post-war northern Korea. Allied forces should not mistake the struggle in a newly unified northern Korea as one for equality; it is a struggle for stability. Enacting Confucian norms and traditions may be initially anathema to the Western mind; however northern Koreans will not accept as legitimate an egalitarian Western system of governance.

Utilizing the Theme of “Juche” in Packaging and Enforcing the Law

While a Confucian rule of law will, in substance, connect with the people of northern Korea, the enforcement and packaging of that law will greatly affect its perceived legitimacy. Utilizing the Kim regime’s theme of juche will innately connect with northern Koreans, giving them a high level of comfort with the new rule of law. In turn, this will reduce violence against the new unified government.

“Juche” is a Korean word that roughly translates as “self-reliance.” This term has special meaning in Korea due to the history of colonialism on the peninsula. After decades of Japanese rule and Soviet influence, the Kim regime pivoted toward a policy of self-reliance and adopted the concept of juche as a driving intellectual force for the regime. Over time, juche became the quasi-religious state dogma in North Korea. Strongly nationalistic, it implies that North Korea needs no help from any other nation to survive. The concept proved remarkably appealing to the people of North Korea. Juche teachings allowed the Kim regime to consolidate absolute power while justifying the nation’s isolation. The Kim regime now ties the idea of juche into every facet of life, from the military to economics to diplomacy. Even the law is justified through juche principles. Co-opting this theme in the packaging and enforcement of the law in northern Korea would pay incredible dividends for the United States and its allies.

As for the packaging of the new rule of law, what may seem like an empty symbolic gesture to the Western mind will be very meaningful to the people of North Korea. For instance, North Korean law is written solely in Hangeul, rejecting any foreign influence in their law. Similarly, any rule of law for northern Korea must be published in Hangeul (Korean script) — not in English, not in Chinese, only in Hangeul. Any whiff of foreign influence on the rule of law will result in immediate skepticism and hostility by the local population. The concept of juche should be utilized in propaganda as a guiding principle in the unification of Korea. This is not an illogical leap considering the unification of Korea will be a moment of nationalistic pride. The rule of law enacted should go so far as to proclaim itself an embodiment of juche principles. Simply wrapping the rule of law in such terms will significantly aid its perceived legitimacy.

Juche must also be apparent in the enforcement of the rule of law. In enforcing the rule of law, allied forces must also rely on what I term “Koreafication.” Koreafication involves South Korean forces and Seoul being the driving force behind rule of law in northern Korea. Koreans must be the face of any military force. The Kim regime spent decades cultivating the notion that outside cultures cannot be trusted through the theme of juche. This must be leveraged to the advantage of allied forces and against Chinese interests in the region. While South Korea has evolved into a society uniquely different and apart from the North, it retains some common bonds. As Jin Lee put it in a 2000 article, Korea “shares [the] same language, early histories and traditions, and one ethnicity; therefore, the sense of Korean identity, historical unity, and destiny would be unfulfilled until the unification.” Forward operating bases in northern Korea must be manned by South Korean forces, not Americans.

Due to the advanced warfighting capability of U.S. forces, this will be a difficult strategy to accept. However, the goal is not to win a fight, it is to be viewed as the most legitimate authority. By using primarily South Korean forces in the northern region of Korea, the unification of Korea would not be seen as an occupation but can be sold as a return to unified self-reliance.

In sum, co-opting the theme of juche will grant the rule of law legitimacy and favor in the eyes of northern Koreans. While Westerners (and even South Koreans) may view juche as an ultra-nationalistic and backwards view of the world, it will retain tremendous cache with the local population. Leveraging juche in the pacification of northern Korean will be of tremendous importance.

Conclusions

The task facing allied forces in building the rule of law in postwar northern Korea cannot be understated. In postwar northern Korea, allied forces will not simply enter unknown territory culturally. A rule of law must be created for a closed culture unexposed to traditional legal concepts. In a post-unification Korea, applying U.S. or South Korean law to the northern region would prove unworkable.

Without a legal system that is understood and accepted by the local populace, much like in Iraq, the country will revert to a broken and unjust system like that of the prior regime. For this reason, the rule of law in northern Korea must be something unique and tailored to the history of the peninsula. This new canon of law must be sold as a return to traditional Korean roots. In order to legitimize the rule of law in northern Korea, its characteristics must reflect the shared Korean Confucian legal tradition as well as have a strong juche flavor. Such a legal system will be accepted by the populace of northern Korea. The work on crafting this rule of law must begin now.

Major John Reid is an assistant professor of law at the United States Air Force Academy. He has both deployed to and spent a 365-day remote tour in the Republic of Korea. While stationed in Korea he worked on issues of criminal jurisdiction, the law of war, and international law. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.