Since mid-June, after some Indian troops crossed the border and entered into what China considers its area of the Donglang (Doklam or Doka La) area, the two countries have been engaged in a standoff.

The China-India border hasn’t been demarcated completely, and so there have been frictions between the border troops of the two countries from time to time. But this time, the situation is quite different. While face-offs in the past have usually occurred in the western and eastern part of the Sino-Indian border, this time it occurred instead in the Sikkim section or the middle part.

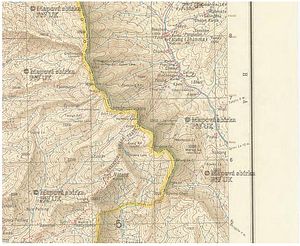

China holds that the Sikkim segment of the China-India borderline has already been delimited by the 1890 Convention between China and Great Britain Relating to Sikkim and Tibet (the 1890 Sino-British Treaty), which is recognized by both China and India. From a Chinese perspective, this is the case because several Indian officials have confirmed this on various occasions, including during meetings between special representatives on the Sino-Indian boundary issue.

So, from Beijing’s perspective, clearly Indian troops entered into the Chinese territory illegally. In fact, because there is no dispute between China and India on the Sikkim segment of the borderline, this is not really an issue between China and India.

After the standoff began, India suggested that it entered into the Donglang area in order to stop road construction by China, allegedly because Bhutan’s foreign ministry declared that the Chinese road may penetrate into Bhutanese territory and had asked China to return to the status quo before June 16, 2017. Essentially, India is conceding that it is seeking to claim territory on behalf of Bhutan.

The Indian position in and of itself implies that it tacitly admits that this is not a problem between China and India. Rather, India is just a third party. But irrespective of how India frames its arguments, the reality is this: no matter what kind of “special relationship” New Delhi has with Bhutan, it has no right to interfere in this issue according to universally recognized international law because Bhutan is an independent country.

By doing so, India is reflecting what some regard as its long-held ambition to control the Indian subcontinent and treat the small countries surrounding it, including Bhutan, as effective client states. When Bhutan showed some signs of improving its ties with China, which is understandable, this alarmed India. New Delhi no doubt sees this as an opportunity to drive a wedge between China and Bhutan and maintain its control of Thimphu.

Though it is true that the border issue between China and Bhutan hasn’t been settled yet, the two sides have been engaged in 24 rounds of negations and should be entitled to work out their differences independently without interference. It is also important to bear in mind that from a Chinese perspective, because Beijing has always emphasized that the Donglang area belongs to China, it therefore follows that the construction of a road is a normal activity in this own territory.

Indian conduct during the standoff is also no doubt partly motivated by broader geopolitics. One explanation for India’s actions is that, just as Indian media outlets have said, New Delhi is concerned that the Yadong Area in China’s Tibetan Autonomous Region is a dagger aimed at the India’s vulnerable “Chicken-Neck” area of Siliguri with a thin strip of land separating India and Bangladesh. If China builds roads in this area, it will quickly cut off the connection between the northeastern part of India and the rest of the country if a war breaks out.

The recent standoff between the two Asian giants is also a reflection of India’s deep distrust and strategic anxiety towards China. Although both China and India are rising, the gap between the two has not narrowed, but widened, in the last two decades. This reality, combined with the bitter memory left by the Sino-Indian war in 1962, colors the Indian attitude towards China even today. Rising nationalist sentiment since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took power has only worsened ties between the two sides, as evidenced by the rhetoric we have seen from some senior Indian officials since the standoff began.

Some Indians also tend to look at the Sino-Indian relationship through a prism of broader geostrategic competition. In recent years, India has frequently complained about the Chinese navy’s increasing activities in the Indian Ocean. In addition to this, because of the ongoing India-Pakistan rivalry and the close relationship between China and Pakistan, India has deep doubts about the intentions of China in building the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

In reaction to this, for the past several years, India has intensified its cooperation with other Asia-Pacific powers such as the United States, Japan, Australia, as well as some Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and Myanmar, especially in the security field. This has only further damaged the level of mutual trust between China and India.

So the Sino-Indian standoff is a result of a complex set of reasons, and it cannot be resolved easily. What might be a way out?

China insists that the precondition for any talks or negotiations should be that Indian troops withdraw to their own side of the border, since it was the Indians who entered the Donglang area illegally first. In other words, India must stop its aggressive actions. But up to now, although the two sides have been communicating with each other through various diplomatic channels, India has showed no sign of conceding. Instead, India is reportedly stepping up military preparations on the borderline, which is very provocative.

If the confrontation continues, China will take any measures to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity. India should realize the danger of a continued standoff, which not only damages New Delhi’s interests, but also poses a threat to the stability of South Asia. The best solution is for India to withdraw from the Donglang area and engage in negotiations with China. Otherwise, it may pay a high price for its own actions.

Liu Lin is an associate research fellow in the Chinese Academy of Military Science specializing in Asia-Pacific security.